The gleaming hardware rolled through Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, and the world took notice. Nuclear DF-61 intercontinental ballistic missiles, their sleek forms promising to reach any corner of the globe. The LY-1 laser weapon systems mounted on armoured trucks, designed to blind enemy sensors. The hypersonic Y19 and Y20 missiles, dubbed aircraft carrier killers. Yet this parade of military magnificence concealed a more troubling reality—a disturbing paranoia, a leadership in survival mode sacrificing strategic competence.

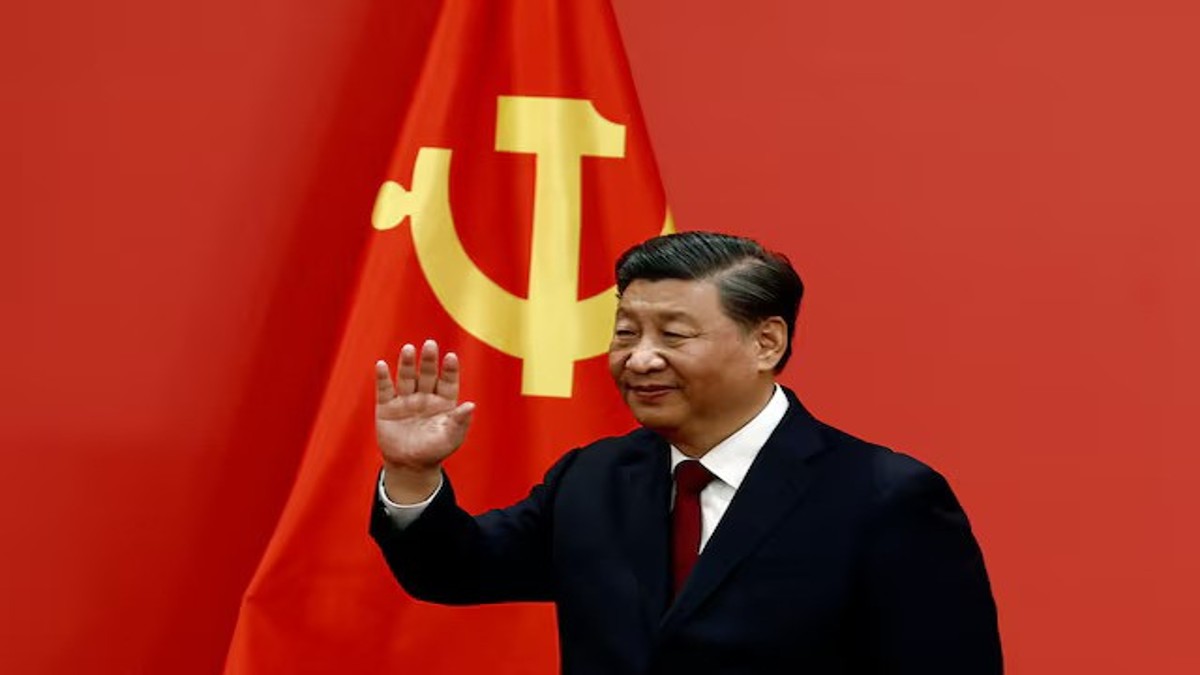

Just weeks after this display, Xi Jinping delivered his most sweeping purge yet of the People’s Liberation Army. Nine generals, including the second-highest-ranking military officer, He Weidong, were expelled from the Communist Party and stripped of rank. The announcement came with the familiar rhetoric of corruption charges, but the scale and timing revealed a butchering of military leadership that bears uncomfortable resemblance to historical Chinese purges that preceded national disasters.

In China, the Party is supreme and was obviously threatened by the military command as it was earlier by tech billionaires. Who can forget that lone man standing up to the tank column in 1989 before the Tiananmen Square bloodbath? Xi Jinping is massively threatened, perhaps even psychologically unstable.

General He Weidong, vice chairman of the Central Military Commission, had been Xi’s own appointee and represented the third-highest military position in China. His removal marked the first expulsion of a sitting CMC general since the Cultural Revolution. Some see his removal paradoxically as a setback for Xi Jinping—his yes-man sacrificed amidst a party power tussle. Alongside He fell Admiral Miao Hua, the military’s top political officer, and seven other senior commanders overseeing everything from the nuclear-armed Rocket Force to the Eastern Theatre Command responsible for Taiwan.

The parallels to China’s imperial past are ominous. During the Qianlong Emperor’s reign in the 18th century, at the height of Qing glory, similar purges preceded catastrophic weakness. The emperor’s distrust of independent military advice created a command structure populated by yes-men forced to hide strategic realities. When the White Lotus Rebellion erupted in the 1790s, the once-mighty Qing forces found themselves unable to suppress a small-time insurgency.

Impact Shorts

More ShortsThe rebellion dragged on for nearly a decade, revealing the hollowness behind imperial military pageantry. The Jiaqing Emperor, inheriting this mess from his father, found himself unable to trust his own commanders. This breakdown in military trust and competence set the stage for China’s humiliation in the Opium Wars.

Xi’s pattern of purges mirrors these historical dynamics with disturbing precision. Since taking power in 2012, he has removed a staggering 30 per cent of the generals he personally appointed.

The timing of these purges is particularly significant. They occurred just days before the Communist Party’s Fourth Plenum—clear political messaging. By reducing the Central Military Commission to just four members, its smallest composition in Chinese history, Xi has concentrated military power to an unprecedented degree. Yet this concentration comes at the cost of institutional expertise and trust.

The corruption charges, while potentially valid, signal a double hollowing: military weakness and a demand that political loyalty override military competence. The official statement emphasised that the expelled generals had committed offenses involving “disloyalty” and had “lost their chastity as Communists”. So ideological conformity, not professional capability, decides one’s place. The purge complicates military decision-making in the South China Sea, Taiwan scenarios, the Himalayan standoff with India, and across the board facing Trump’s America.

The imperial precedents suggest where this path leads. Qianlong’s military, despite brutal imperial victories over Tibet and Xinjiang, became increasingly hollow. This left the command structure incapable of effective response, and China was carved up by Britain and later Japan.

Xi’s current military faces analogous dangers. The impressive weapons systems displayed in Beijing’s parade represent genuine achievements, but their effectiveness depends on command structures capable of employing them strategically—that’s now gone.

The historical pattern extends beyond individual reigns. Chinese military disasters have repeatedly followed periods when political purges weakened command structures. The late Ming collapse, the Qing defeats in the Opium Wars, and even aspects of the Chinese performance in the Korean War all reflected institutional weaknesses created by political interference in military affairs. Xi Jinping has disrupted institutional memory and created gaps in strategic planning. Modern military systems require years of experience to master, and the integration of complex technologies demands stable leadership capable of long-term planning.

The international implications extend beyond China’s borders. The repeated purges create uncertainty about Chinese military capabilities and decision-making processes that could lead to miscalculation in crisis situations. When military leaders are primarily concerned with political survival, their behaviour becomes unpredictable in ways that increase the risk of conflict escalation.

Xi’s approach reflects a broader misunderstanding of military effectiveness that has plagued Chinese imperial traditions. The emphasis on personal loyalty over institutional competence creates systems that work well in peacetime parade conditions but fail under the stress of actual conflict. Put differently, China is compromising strategic flexibility.

The result resembles the late imperial pattern where impressive technology coexisted with ineffective command structures. The Qing had access to firearms and artillery that should have provided advantages, but poor leadership and training rendered these weapons ineffective in actual combat.

As the ancient Chinese understood, effective leadership requires more than personal loyalty. The famous metaphor of “dragons without heads” perfectly captures the current situation. When powerful forces lack effective leadership, they become sources of chaos and misdirection. The shiny hardware represents enormous potential power, but without competent command, it becomes as dangerous to its own holders as to its enemies.

Like emperors Qianlong and Jiaqing before him, Xi appears to believe personal loyalty can substitute for competence and political control outweighs military effectiveness. The imperial archives record the consequences: humiliation, defeat, and the collapse of dynasties that once seemed invincible. In the end, as Chinese wisdom has long recognised, a boat without a skilled helmsman will founder regardless of how magnificent its sails appear—and in Xi’s military, the headless dragons may soon find themselves flying not toward victory, but toward the very disasters their purges were meant to prevent.

The writer is a senior journalist with expertise in defence. Views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect those of Firstpost.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)