In the Japanese cyberpunk masterpiece Ghost in the Shell, citizens exist as ethereal souls inhabiting temporary shells, their humanity preserved in digital networks even as their physical bodies fade away.

Today, Japan faces a strange reality: its population is shrinking, and its ageing people are slowly increasing in number. The country that once inspired the world with its technology now faces a deep crisis—one that no advanced machines can fix, as something essential is being lost.

The Numbers Behind the Phantom

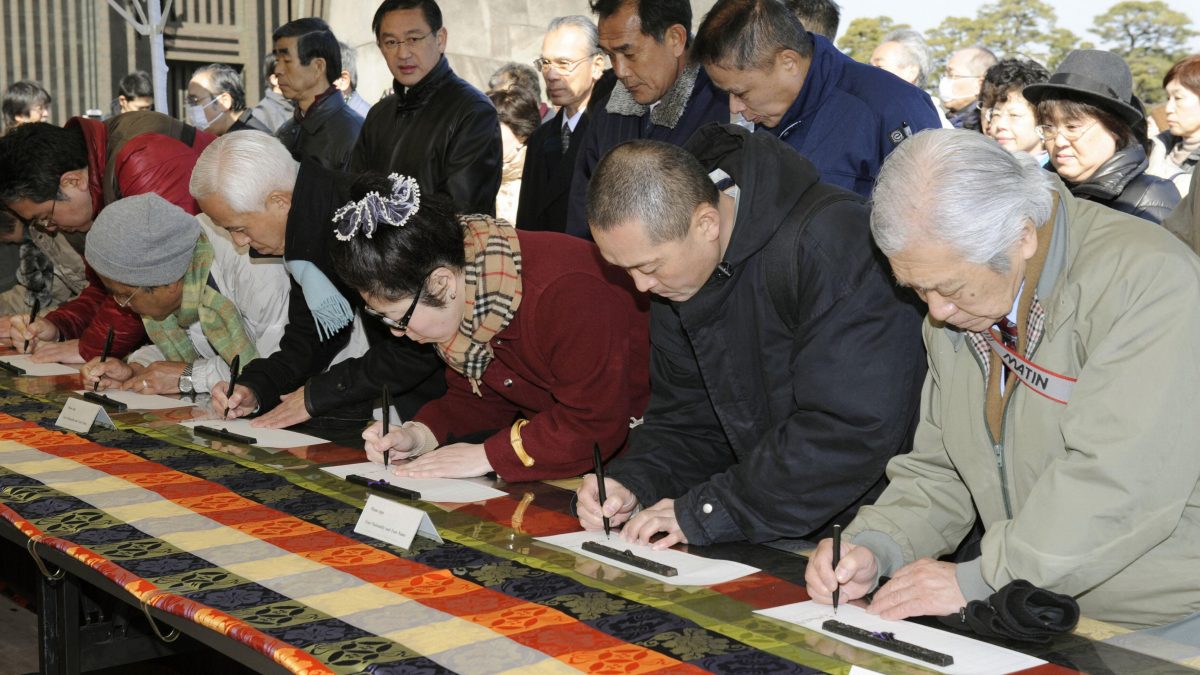

Japan’s demographic collapse reads like the opening credits of a dystopian anime. With nearly 100,000 centenarians—the nation celebrates a grim milestone that is ironically a massive medical triumph. The centenarians are a part of what researchers term a “super-ageing society”, where the elderly constitute an unprecedented 30 per cent of the population.

The arithmetic of decline is unforgiving. In 2024, Japan recorded just 686,000 births, the lowest figure since records began in 1899—a number representing barely one-fourth of the 2.7 million births recorded during the postwar baby boom. Meanwhile, deaths exceeded births by over 900,000 annually. This is unsustainable demographic haemorrhaging.

By 2040, Japanese media reports the labour shortage is expected to be a staggering 11 million workers, roughly equivalent to the population of the Netherlands. Japan’s population will plummet 30 per cent by 2070, with those aged 65 and older comprising 40 per cent of the total.

Japan’s Ageing Tsunami the Vortex

What drives Japan’s demographic collapse extends far beyond simple fertility statistics. The nation’s total fertility rate has stagnated at 1.15 children per woman—far below the 2.1 replacement level necessary for population stability.

Impact Shorts

More ShortsJapan’s rigid work culture remains a primary deterrent to childbearing. At the heart of the declining birth rate is the traditional work culture, a model that makes family time almost a taboo. The expectation is that work must have priority over family, and 14-hour workdays are routine.

Childcare costs at an average of $700 per month despite a heavy government subsidy compound these challenges. The shortage of childcare facilities exacerbates the problem, with waiting lists that force parents to delay career plans or forgo additional children entirely.

The declining marriage rate itself reflects broader social changes. Many Japanese are now choosing to remain single.

Japan’s response to its demographic crisis reveals both technological innovation and fundamental limitations. The nation has invested heavily in robotics, roughly half a billion dollars per year. Current robotic solutions are confined to monitoring systems used in nursing homes, some mobility assistance robots, and a few advanced humanoid prototypes like AIREC, which costs approximately $67,000, equal to 3 years of an experienced caregiver. However, the limitations of robotic eldercare become apparent, as they don’t have the bandwidth yet to let elderly be without human oversight even for diaper changes. Neither can they provide emotional validation or complex medical awareness.

Most critically, robots cannot address Japan’s core demographic challenge. They cannot reproduce, consume goods and services, or contribute taxes.

The Immigration Paradox

Japan’s homogeneous society confronts an uncomfortable reality: immigration represents the most viable solution to demographic decline, yet remains politically and socially challenging to implement. Foreign nationals now comprise nearly 3 per cent of Japan’s population, reaching an unprecedented 3.67 million as of January 2025. This is not sitting well with too many, as Japan, like Switzerland, is an insular place.

Recent electoral gains by nationalist politicians underscore the political constraints on immigration expansion.

The Ghost in Japan’s Shell

Like the cyborgs in Masamune Shirow’s prescient manga, Japan’s demographic crisis represents more than statistical decline—it embodies the tension between maintaining cultural identity and ensuring national survival. Like Major Kusanagi contemplating her ghost within the shell, Japan must determine which elements of its identity are essential and which can be sacrificed for survival.

As centenarians accumulate and births plummet, Japan’s future resembles the ethereal networks of “Ghost in the Shell”—a society where the physical foundation steadily dematerialises while the institutional memory persists. The question remains whether Japan can find a way to accommodate its cultural essence into a new demographic reality, or whether it will fade into an ageing twilight.

The writer is a senior journalist with expertise in defence. Views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect those of Firstpost.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)