Walking around the grand boulevards and streets of central Vienna, it is hard to imagine that the area’s UNESCO World Heritage Site classification has got an unpleasant suffix: In Danger. But it is, embarrassingly so in fact, alongside places where there are wars or conflicts raging — Kyiv in Ukraine and Aleppo in Syria, for example. And yet Austria is not a battlefield, nor in the hands of power-hungry dictators. And yet the “Historic Centre of Vienna” has been red-flagged.

All because of a development project that proposes an ice-skating rink with a hotel and shopping centre in a glass-fronted tower, bang in the middle of the grand Baroque architecture of this former capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. And even more amazingly, Vienna has been in UNESCO’s bad books since 2017 but the impasse continues as the project has been altered significantly —in terms of tower height, for instance— but remains far from being totally scrapped.

New Delhi might just find itself keeping company with Vienna on this score if UNESCO gets wind of the “proposals” for some heritage sites in the city, as part of the central government’s ‘Adopt a Heritage’ scheme, which covers several historic monuments including three in the international body’s list. And it is alarming because UNESCO has often unilaterally shown the red card without asking the ‘State Party’ (the government of the country) for clarification.

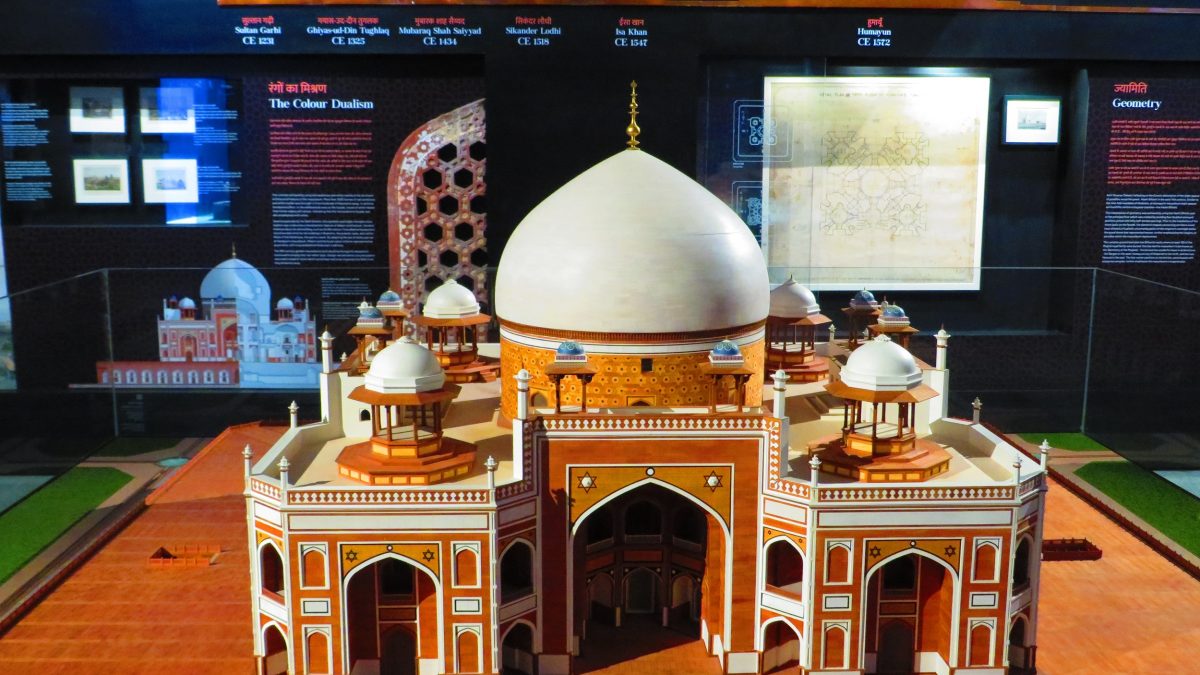

The Union Culture Ministry has denied that the Humayun’s Tomb complex will get a restaurant and café inside the premises, an elevator for easier access and a sound and light show to liven up the funerary complex, as per the plan proposed by the private company which has won the ‘adoption’ contract. But there is no clarity yet on how many of the avant garde proposals have actually been rejected — or accepted by the ministry and the Archaeological Survey of India.

Impact Shorts

More ShortsThere is also the question of what has been proposed for other “heritage” sites also cleared for “adoption” by the same private company, including the UNESCO World Heritage Site-listed Qutab complex in Mehrauli and Safdarjang’s Tomb. The firm has already adopted Red Fort, the third UNESCO listed monument in the national capital without ruffling too many feathers, but its purported plans for the three recently “adopted” heritage sites has caused considerable unease.

Many cities that contain UNESCO World Heritage Sites have grumbled about the development constraints that such “recognitions” entail, particularly when it comes to architectural changes, which is also the crux of Vienna’s problem. Of course, the issues with the proposed “facilities” at Humayun’s Tomb and other “adopted” monuments in Delhi centre mainly on their appropriateness in funerary and/or religious complexes, both architecturally and culturally.

Even so, the proposal and the ensuing “controversy” provide an opportunity to debate some hitherto under-articulated issues. It goes without saying that food and drink outlets at tombs and other sombre places such as memorials —even on the periphery— are inappropriate. As also, sound and light shows. But surely there cannot be a blanket ban on such facilities at all “historic” or “heritage” spots? It should depend on the context and on their proposed placement.

The issue of elevators on a medieval monument is, on the face of it, a definite no-no. Perhaps if its only utility is to take people to a rooftop restaurant, I would agree that it should not be allowed. But the broader issue of lifts for accessibility, even at World Heritage Sites, cannot be ruled out. More so as there are good examples of elevators being seamlessly integrated into monuments, as is the case with the 15th century Mehrangarh Fort, where it was installed in 1995!

In fact, that fort —private property of the erstwhile royal family of Jodhpur and managed by them via a trust— is a prime example of a heritage complex that has been modernised thoughtfully and provides facilities such as elevators, food and shopping without compromising on the character and gravitas of the fortress, which is around 110 years older than Humayun’s tomb and contains a museum and resource centre besides several palaces and very popular temples.

Being official World Heritage Sites, however, means that scrutiny of all changes inside the Humayun’s Tomb complex and the one at Mehrauli will be more intense and critical than at a private fort. The plans submitted by the private company include existing examples of what they propose, but without extensive and public explanations of what these actually entail, there will be doubts and alarm. And that could result in UNESCO taking a dim view of the plans.

My recent visit to Budapest, however, revealed UNESCO does make exceptions. Key parts of the city are designated a World Heritage Site including the medieval Buda Castle District. But there’s a hotel with a distinctly 1970s design —albeit pre-dating the UNESCO designation by a decade— right in the middle of the area, incorporating the ruins of 13th century cloisters; UNESCO doesn’t mind, it seems. The Indian chess team stayed at the hotel during the recent Olympiad!

A little way down the hill from Buda Castle is a very intriguing convention centre and restaurant complex, which came to mind as news emerged about the private company mulling such a facility at the Mehrauli World Heritage site much to the consternation of Indian conservation experts. It is called Aranybastya (Golden Fort) after the 16th century Turkish bastion that existed there before a Baroque era residence, which was also destroyed during World War II. And rebuilt.

In fact, it was rebuilt brilliantly incorporating the remnants of the Turkish era bastions into the auditorium, making for a uniquely atmospheric venue, redolent of Hungary’s history, including the time when Old Buda had become a Muslim majority city. The architects even found place within the new structure medieval artefacts that had been retrieved during the digging for the construction. If anything, this imaginative fusion enhances Budapest’s World Heritage tag.

India has enough monuments and spaces around them that can be innovatively used to provide amenities and attractions for different categories of visitors without disrespecting the legacies they embody. These could make the areas more relevant and important to the communities that reside around them — which also happens to be one of the objectives of the UNESCO heritage certification.

A “convention centre” in a tomb that becomes a space for weddings or rock concerts should not be allowed, but nor should there be a “one size fits all” ban on modern facilities in and around monuments. Vienna and Budapest showed me the good and bad points about projects inside urban World Heritage Sites. Those who decide about the future development of New Delhi’s monuments have many good precedents to follow to avoid a Vienna-type red flag by UNESCO.

The author is a freelance writer. The views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not n__ecessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)