Oui, monsieur Macron, vous n’êtes pas De Gaulle. Yes, Emmanuel Macron isn’t Charles de Gaulle.

The French President never misses a chance to channel his ‘inner De Gaulle’ even if it becomes a spectacle of self-flattery.

As Covid-19 hit Europe in 2020, Macron landed in the UK to award London the Légion d’honneur on June 17, 2020, on the 80th anniversary of De Gaulle’s famous June 18, 1940, Appeal speech, in which he exhorted the French to rise against the Nazi occupation.

“Whatever happens, the flame of the French resistance must not and will not be extinguished,” De Gaulle told his countrymen in the five-minute, 400-word speech.

A Brigadier General and the under-secretary of state for national defence, De Gaulle had fled to London as Marshal Philippe Pétain planned to sign the armistice with Nazi Germany after the defeat in the Battle of France.

The year also marked the statesman’s 130th birth and 50th death anniversary. Macron, who had declared 2020 as the Year of Charles De Gaulle, laid a wreath at his statue in London.

Impact Shorts

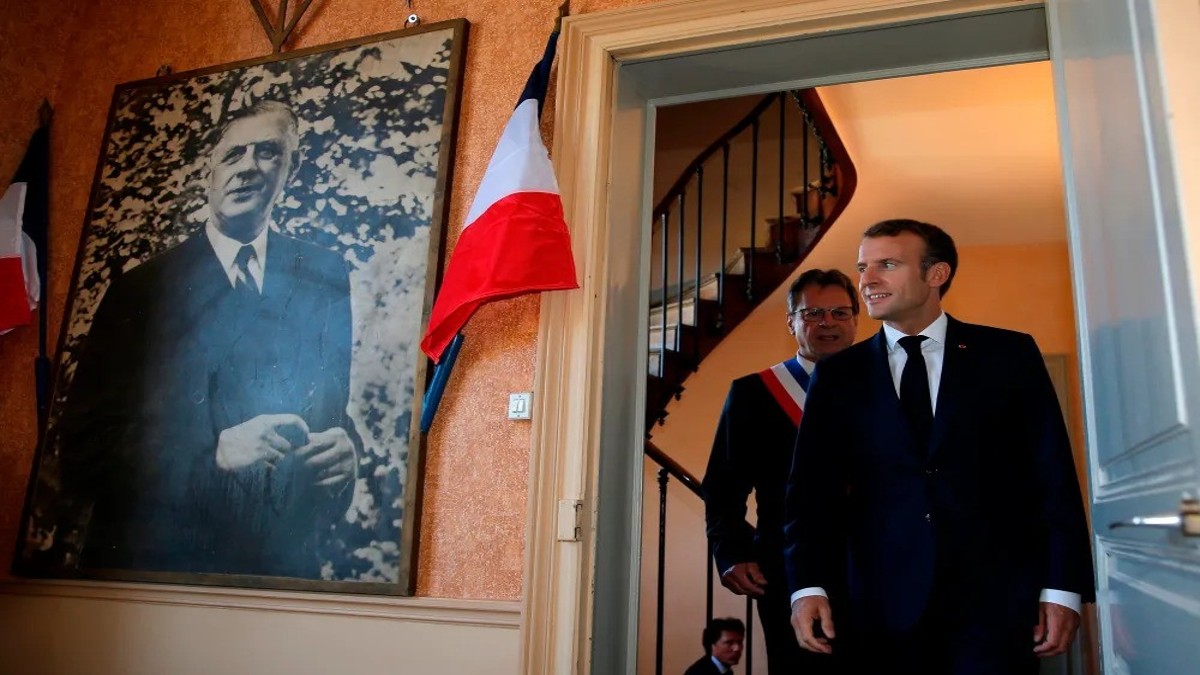

More ShortsBattling low approval ratings since 2018, Macron tried to portray himself as a modern-day De Gaulle, who also believed in France’s greatness, self-sufficiency and patriotism. Later, on November 9, he paid tributes to the General at his home at Colombey-les-Deux-Églises on his 50th death anniversary.

Macron delusional about being De Gaulle

Macron’s reverence for De Gaulle is universally known. He keeps his memoirs on his desk and the hero’s picture in his study.

However, being a Gaullist is easy in words, not action—and Macron miserably fails to understand this.

It’s impossible to emulate a war hero who led France against the Nazis in World War II, returned from exile twice to lead the country and united the French, gave his country its “politics of grandeur”, carved an autonomous identity outside the influence of the USA and the UK and made France the fourth nuclear power.

Unlike Macron, who has no military background or experience, De Gaulle was a war hero. In WW I, he was shot at one knee in the Battle of Dinant. Subsequently, he was seriously wounded in a bayonet fight in the Battle of Verdun, the longest and the bloodiest battle of the conflict, and captured.

At the start of WWII, De Gaulle commanded a tank brigade attached to the French Fifth Army and was promoted to Brigadier General in the 4th Armoured Division.

A relatively unknown Army officer, especially among Frenchmen, De Gaulle rallied the French and often fought with Winston Churchill and FD Roosevelt for France’s identity during WWII.

De Gaulle’s relentless fight with Churchill and Roosevelt for

France ensured that the country be counted among the victors of World War II, get a permanent seat in the UNSC and the Allied Council of Foreign Ministers in Europe and its occupation zone in Germany. He rescued France from the Algerian imbroglio, prevented a civil war and withdrew from NATO’s integrated military command.

Macron isn’t even a pale reflection of De Gaulle and lacks his stature and gravitas.

In trying to be a modern-day De Gaulle, Macron tried to represent Europe as Russia was preparing to invade Ukraine. He flew to Moscow to convince Vladimir Putin to stop his forces but unsurprisingly failed.

Macron was unrelenting. Convinced of his diplomatic powers and to impress voters in the April presidential election, he called Putin on February 20, four days before the war, to persuade him to meet American President Joe Biden in Geneva.

Putin, who was at the “gym” and “wanted to go for ice hockey”, agreed in principle. Not sensing the Russian president’s joke and insult, Macron was excited. The Elysée issued a statement about the Geneva meeting.

Putin and Biden never met.

On February 21, Putin officially recognised the two separatist provinces of Luhansk and Donetsk, in eastern Ukraine, and launched his “Special Military Operation” on February 24.

A documentary released in July 2022 showed Macron’s failure as he talked to Putin for hundreds of hours on the phone to convince him not to attack Ukraine.

Realising that Putin had taken him for a ride and his diplomacy had failed, Macron resorted to cosplay and literally pantomime photoshoots to show off his highly doubtable aggressive side to the world, particularly Russia.

In March 2022, he imitated Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s attire. With the presidential election approaching, Macron organised a photoshoot to burnish his ‘tough guy’ image. He donned a French special forces hoodie and denims with an overgrown stubble and dishevelled hair—as if Élysée’s Golden Room was a war bunker and he a wartime leader.

In February this year, a reckless Macron mentioned the possibility of sending European troops to Ukraine.

In March, more theatrics followed. Photos showed Macron in a tight black t-shirt hitting a punching bag. Some X users questioned whether his biceps were digitally enhanced.

The Opposition criticised and mocked Macron.

However, the De Gaulle in Macron was roaring. In an interview with The Economist in May, he reaffirmed the possibility of sending troops to Ukraine.

Soon, Moscow responded, “If the French appear in the conflict zone, they will inevitably become targets for the Russian Armed Forces,” Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova told the media in Moscow.

In the same week, Macron made a U-turn after all the bombast when Putin ordered his forces to rehearse deploying tactical nukes in response to “threats” by the West. “We are not at war with Russia or the Russian people,” Macron said at a joint news conference with visiting Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Macron can’t be blamed for his desperation to don the mantle of the legendary and iconic military officer, statesman and president.

Gaullism is entrenched in French politics.

De Gaulle’s imposing physical presence and his indomitable spirit in the face of Nazi aggression, patriotism and love for France have placed him in the pantheon of Napoleon Bonaparte, Louis XIV and Joan of Arc.

Revered and reviled, loved and loathed and adulated and mocked, the war-time leader and founder of the Fifth Republic (1958) was a towering figure who’s pervasive in French politics more than five decades after his demise.

The right, far-right, centre, left and far-left—all embrace him. Marine Le Pen renamed her father’s party, Rassemblement National (National Front), to De Gaulle’s party, Rassemblement du peuple français (Rally of the French People). The left, which accused him of being a dictator, now praises his honesty and love for France.

Macron imbibed De Gaulle’s flaws, not strength

In his biography, War Memoirs, De Gaulle’s first sentence reads: “Throughout my life, I have had a certain idea of France.” But his authoritarian disposition and monarchical ambition were intertwined with that “idea” of France.

Later, he said: “La France, c’est moi (France is me).” He wrote in his memoirs: “My conception of the state comes from a great synthesis of French history, which includes the Revolution, but also the Ancien Régime and Napoleon.”

De Gaulle symbolised Gallic unity and strength but would brook no criticism or contrary opinion. “I have heard your views. They do not harmonise with mine. The decision is taken unanimously,” he said.

The May 68 civil unrest by students and workers paralysed the economy and the government. De Gaulle played the first gamble calling for a referendum and warning of civil war only to inflame the protests. He admitted his miscalculation to Prime Minister (PM) Georges Pompidou: “For the first time in my life I faltered.” On May 29, he fled to West Germany.

After Pompidou signed the Grenelle Agreements with trade unions and employers, the protests gradually receded and a counter-protest was held by De Gaulle’s Union for the Defence of the Republic party.

A pumped-up De Gaulle returned on May 30 and took the second gamble. He dissolved the National Assembly and called for a parliamentary election. De Gaulle’s party surprisingly won 353 of the 486 seats—for the moment, his gamble paid off.

However, he paid for his hubris one year later. His third gamble was the April 27, 1969, referendum, which proposed classifying Regions as Territorial Collectives and combining the Senate and Economic and Social Council into a new powerless upper House. Many believed that he wanted to curtail the Senate’s powers in the garb of decentralisation.

An overconfident De Gaulle announced that he would resign if he lost the referendum. To his consternation, 52.4 percent of voters rejected the changes, and he resigned.

De Gaulle introduced Article 49.3, which allows the government to pass a Bill in the National Assembly without a majority of the votes. While the Article, according to him, ensured that people’s will prevailed, it has been used by successive governments 100 times—at times to impose their will—since 1958.

Macron’s arrival was like De Gaulle’s entry after a 12-year exile following the Fourth Republic’s collapse during the Algerian War of Independence.

Macron caused a political earthquake when the 39-year-old canny former investment banker and then-President François Hollande economy minister romped to the Élysée Palace in 2017.

France, eager for a change after Hollande, the most unpopular

president under the Fifth Republic, was hooked to a young and dashing political novice with a reformist agenda and the grassroots movement of his En Marche! (now Renaissance) party. He won 66.1 per cent of the votes.

However, within a year, Macron’s approval rating dived to 29 per cent with no major change in the economy and employment figures and pensioners and low-income workers saw him as pro-big business and rich.

Macron’s 2022 re-election already polarised France. His Ensemble (Together) coalition beat Le Pen in the second round by winning 58.55 per cent of the votes against 41.45 for her. However, the margin had reduced compared with their 66.1 per cent to 33.9 per cent in 2017 with her party adding around three million votes.

Macron acknowledged, “Our country is beset by doubts and divisions”. Le Monde dubbed his win “An evening of victory without a triumph”. Macron’s success until this year’s election can be attributed to only his middle- and upper-class urban voters, who wanted to keep the far-right out of power.

In his frenzied mission of emulating De Gaulle, Macron has imitated his flaws, not strength.

Like De Gaulle’s “excessive self-assurance” and his “harshness towards other people’s opinion”, Macron, against the advice of his aides, called the snap election following the rout of Ensemble in the European Parliament election.

The first round of voting showed how a majority of voters hated Macron and preferred the far-right. Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (National Rally) won 33 per cent of the vote, the leftist New Popular Front (NFP), which has radical leftist leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise (France Unbowed) as the largest party, around 28 per cent and Ensemble only about 20 per cent.

Alarmed at the far-right’s win, Macron stitched a last-minute alliance with the NFP to keep the far-right out of power in the second round of voting.

Macron failed again.

None of the blocs secured the majority mark of 289 of the National Assembly’s 577 seats. The NFP grabbed 181 seats, Ensemble 161 and Le Pen and allies 142.

The NFP wants to increase public spending and minimum wages, reverse Macron’s economic measures, especially the much-hated and controversial pension reforms, and reintroduce and increase the wealth tax to raise €15 billion.

Macron hopes to form an alliance with the left coalition but without France Unbowed.

And neither the left nor the centrists want to form a coalition government with the far-right.

PM Gabriel Attal, a member of Renaissance, has criticised Macron for calling the snap polls. In a sign of further divisions between the two, Attal has been elected his party’s group leader with 84 of 98 lawmakers voting for him.

The three-way unprecedented division of France between the left, Centre and the right has paralysed government formation. Investors are wary and France’s future role in the European Union and NATO could be weakened, in case of a coalition government comprising parties with opposite thinking.

De Gaulle only in words, not action

De Gaulle is credited with Trente Glorieuses, a 30-year unprecedented growth in which the state controlled the capitalist economy substantially unlike the Soviet Union’s central planning. His dirigiste economic policy directly controlled the markets, but France continued to be a capitalist economy.

Trente Glorieuses was characterised by rapid growth, high productivity, wages and consumption and better social benefits with the standard of living becoming one of the world’s highest. In his book ‘THE NEW FRANCE, A society in Transition, 1945-1977’, late British journalist and writer John Ardagh writes that the average French worker’s salary galloped by 170 per cent and private consumption by 174 per cent.

Domestically, Macron’s disastrous bid to be De Gaulle resulted in him being labelled the “President of the rich”, who was out of touch with reality.

While disgruntled pensioners protested the reduction in pensions, which was intended to make higher social security contributions, Macron invoked De Gaulle.

During a ceremony marking the 60th anniversary of the French Constitution at Colombey-les-Deux-Eglises in October 2018, he told an old woman that she should complain less .

“The grandson of the General told me earlier that the rule in front of his grandfather was: ‘You can speak very freely; the only thing you are not allowed to do is complain.’”

Macon was victorious in 2017 on the promise of increasing growth, purchasing power and foreign investment and reducing unemployment.

In the first five years of his presidency, the 2021 GDP reached 7 per cent, unemployment rate decreased to 7.4 per cent in the fourth quarter (the biggest fall since 2008) and France beat Germany and the UK in foreign investment.

However, as Hollande said in 2017 that his protégé helped the rich “get richer” at the cost of the poor, Macron scrapped the wealth tax and introduced a fixed one-time levy on capital gains to boost investment, cut labour costs, reduced social security contributions for employers and changed the labour code to help companies lay off employees without a reason.

By 2020, as the quality and duration of employment decreased, 1.9 million individuals weren’t seeking employment, which was reflected in the reduced unemployment rate. The purchasing power of the wealthiest rocketed while that of the poorest tanked. The number of jobless at the end of the fourth quarter in 2023 was 2.3 million, an increase of about 6,000 from the previous quarter.

In January 2018, Macron’s approval rating sank to 47 per cent and further to less than 25 per cent as the Mouvement des gilets jaunes (Yellow Vests Protests), triggered by high fuel prices and cost of living and rising inequality, engulfed France by November.

In March 2023, Macron rammed the controversial pension reforms, which increased the retirement age from 62 to 64, through the National Assembly despite vociferous opposition and nationwide protests using Article 49.3. The Bill’s passage triggered more protests and two no-confidence motions.

Article 49.3 has been used 11 more times by the current government to push through Bills rejected by an overwhelming majority of the people. De Gaulle aimed to enforce people’s will via Article 49.3. Macron wants his way by using the constitutional provision.

The anger over the pension reforms had barely cooled when Macron announced massive labour reforms to ensure social justice, raise salaries and achieve full employment by the end of his second term in 2027. However, the measures were criticised for favouring companies and harming the interests of workers.

After a two-year rise in inflation—6.3 per cent annualised rate early last year—the prices of energy, gas and food and an unmatched rise in wages pinched lower- and middle-class voters, whose purchasing power had decreased.

The national debt of EU’s second-largest economy has spiked to 112 per cent (€3 trillion) of GDP from 97 per cent in 2019 and 65 per cent in 2007, according to the IMF.

De Gaulle hated both communism and capitalism. “Capitalism is not acceptable in its social consequences. It crushes the humble and transforms men into wolves who hunt other men,” he wrote in his memoirs.

Macron’s measures were pro-business and anti-poor. He forgot that De Gaulle advocated an association between capital and labour with workers participating directly in the company’s management.

De Gaulle’s aim to make the executive most powerful was to curb the powers of bureaucrats, special interests and political elites. On the other hand, Macron pleased large companies at the cost of piling up austerity on the common man.

From an unknown two-star General who challenged Pétain to become PM and then president, De Gaulle governed for 11 years, oversaw an economic boom and steered France through decolonisation.

De Gaulle had flaws: arrogant, elitist, obstinate, presumptuous, dismissive and even delusional. But he delivered what France longed for: unity, strength, self-

sufficiency and identity.

In his book, A Certain Idea of France: The Life of Charles de Gaulle, British historian professor Julian Jackson, one of the leading experts on 20th century France, writes: “He saved the honour of France.”

Churchill recognised De Gaulle as the leader of the ‘Free French’ despite Pétain being the legal head of state. The British PM had his reasons. “Given de Gaulle’s total obscurity in 1940, Churchill’s decision to back him was certainly quixotic. De Gaulle’s personality appealed to Churchill’s romantic imagination, and he had been genuinely impressed by his force of character on the few occasions they had met,” Jackson writes in another book titled De Gaulle.

Their relations soured as De Gaulle dug his heels against British dominance during WWII, but Churchill later wrote: “He had to be rude to the British to prove to French eyes that he was not a British puppet.”

A day after Paris was liberated, Marianne welcomed De Gaulle with open arms. As he walked down the Champs-Élysées with government officials, Conseil National de la Résistance (National Council of the Resistance) and senior French military leaders, overjoyed Parisians converged along the route to Notre-Dame Cathedral. Amid cheers and welcome, he was legitimised as France’s leader.

The French rejected De Gaulle in the 1969 referendum, but Gaullism was immortalised. In A Certain Idea of France, Jackson writes that De Gaulle’s death in November 1970 “was one of the most intense moments of collective emotion in the history of modern France”.

Le Figaro published a cartoon depicting a huge uprooted oak with a weeping Marianne by its side.

Macron won’t have such a lasting legacy. After his second term ends, he won’t be able to contest before 2032—unless he thinks he can make a De Gaulle-like return. His loss of stature and respect can be summed up in the statement of Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT), one of the five largest trade union’s blocs, which compared him to Louis XVI, who was guillotined during the French Revolution in 1793. “It’s like having Louis XVI locking himself away in Versailles.”

The writer is a freelance journalist with more than two decades of experience and comments primarily on foreign affairs. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the writer. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.

)