On the morning of 8 November, Indian Twitter woke up to yet another bizarre national trend: #StopTeluguImposition. Most tweets using this hashtag, written in Tamil, offered little by way of explanation, preferring instead to express anger at the supposed imposition users were facing in Tamil Nadu. Many tweets went a step further, taking the opportunity to rant against Telugu speakers collectively. According to an article by BBC Telugu, the outrage was sparked by the inclusion of Telugu as an optional subject in the curriculum of the Chennai-based International Institute of Tamil Studies (IITS), a state government-run institute. IITS originally offered both Hindi and French as optional subjects; Hindi was replaced with Telugu earlier in November following a controversy, and the budget of Rs 3 lakh allocated for Hindi will now be used for teaching Telugu instead. French remains an optional subject. Given the relatively insignificant size of the budget, and the fact that Telugu remains an optional subject at IITS, the outpouring of anger on social media seems more than a little unwarranted. Nevertheless, examining this closer does offer its own insights. Imposition — a misnomer The use — or misuse, rather — of the term ‘imposition’ was particularly egregious. Imposition is a systematic, structural process, one involving an inherent imbalance in power dynamics, where one camp enjoys a certain institutional privilege over the others. Case in point: the Indian government’s language policy vis-a-vis Hindi, mandating its usage across the length and breadth of the country through its various institutions, even in regions where it is not spoken at all. South Indians in particular have, time and again, rallied against this unfair promotion of Hindi and its underservedly high status in India’s administrative language hierarchy. However, none of this applies to Telugu in Tamil Nadu; residents of the state are not required to learn Telugu in order to avail government services, read forms and documents, or communicate with government officials. Nor are advertisements and communication in Telugu forced upon them. In other words, Telugu is not imposed on Tamil Nadu’s populace in any shape or form.

This outburst of focused anger, albeit from behind the anonymity of one’s online persona, raises an uncomfortable question: Is the mere visibility of a minority language in the public sphere enough to provoke tensions?

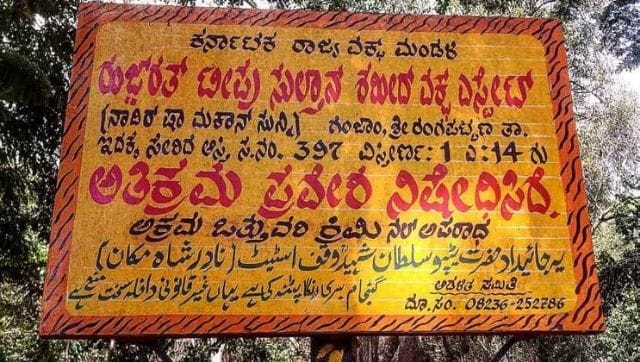

Such a development would point to the increased marginalisation of minority languages, facilitated by linguistic nationalism. Sadly, such flare ups are not without precedent. Violence rooted in language Multilingual spaces in modern India, especially leading up to and following the reorganisation of states along linguistic lines in 1956, have often borne witness to skirmishes over language. Bengaluru, a cosmopolitan city that has long been multiethnic, has been a site for many such clashes. The city’s Cantonment district, once administered by the British Indian Army, was and is primarily Tamil and Dakhni Urdu-speaking, with Kannada introduced to the area only in the decades following Independence. Historian Janaki Nair has chronicled these developments in her writings on linguistic nationalism in Karnataka. In her landmark essay, Language & The Right To The City, she writes how the visibility of Tamil signage and even movie posters rankled local Kannada nationalists, something they saw as a humiliation, demonstrating a lack of ethnic self-respect that needed to be consciously developed. These tensions came to a head during the Kaveri dispute in 1991, with widespread rioting and violence against Tamil speakers in Karnataka, and against Kannada speakers in Tamil Nadu. Bengaluru’s Tamil community, mostly residents of the city’s Cantonment, posed an especially easy target for local Kannada nationalists. [caption id=“attachment_8280231” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Bilingual Urdu-Kannada signage from Srirangapatna, Mandya district, Karnataka. All photographs are by the author[/caption] To the West, in Kolar Gold Fields, where the local population is almost entirely Tamil Dalit, protests over revisions to Karnataka’s language policy (to make the language mandatory in government schools) during the Gokak Agitation in 1982 resulted in five deaths by police firing. KGF’s residents have also often complained of feeling neglected by the state for their linguistic identity as Tamil speakers in a Kannada-speaking state, compounded by their caste identity. Closer to our own times, the airing of a 10-minute Urdu broadcast on Doordarshan in 1994 led to protests that quickly morphed into riots against Muslims in Bengaluru, with over 25 deaths. Nair writes that M Chidananda Murthy, a noted Kannada nationalist writer, “led the shock troops against the telecast”. Thousands of miles from the South, East India has also seen its fair share of linguistic violence. On 19 May 1961, 11 Bengali language activists in Silchar, Assam, the largest town in the Bengali-speaking Barak Valley, were killed in police firing while protesting a state government circular declaring Assamese compulsory in secondary education. The circular was subsequently withdrawn, and Bengali was made an official language in the valley’s districts. More recently, in 2017, 11 people died in clashes in West Bengal’s autonomous Gorkhaland Territorial Administration, over Kolkata’s decision to make Bengali a mandatory subject in state schools. Although within the political boundaries of West Bengal, Gorkhaland is a primarily Nepali-speaking region where the local language enjoys official status. Of course, these are merely a handful of examples. There exist many more, India’s modern history is littered with them. Multilingual histories As always, the stained lens of nationalism obscures the rich currents of cross-cultural interaction and exchange that characterise India’s vivid patchwork of local socio-cultural histories. The creation of linguistic states in 1956 largely put an unceremonious end to this. British Madras was a major center of Telugu printing, and the de facto capital of Telugu journalism. As anthropologist David Shulman writes, British-era Madras was “the primary site for Telugu literati, the heartland of Telugu publishing”. Madras had a sizeable Telugu-speaking community well into the 20th century, with the 1951 Census recording that the city was ~20 percent Telugu-speaking. Madras bashai, a local Tamil dialect often used in Tamil cinema, features numerous Telugu words as a result of this cultural contact. Madras was also the birthplace of Telugu cinema, as well as its capital until the early 90s, when it was moved to Hyderabad. Madras Presidency’s Justice Party, an important force in early 20th-century India’s budding self-respect based non-Brahmin movement, counted numerous Telugu speaking leaders among its ranks, including some who would go on to become Chief Ministers of Madras Presidency. Centuries before, Madurai and Tanjavur were important centres of Telugu literary production under their Nayaka rulers. When Tanjavur came under the rule of the Marathi-speaking Bhonsle dynasty, Telugu continued to be used as the court language. [caption id=“attachment_8280241” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  “Native” signage from British Bombay, with Gujarati and Urdu in addition to Marathi[/caption] Further North, British Bombay was a melting pot of communities, with Gujarati-speaking Parsis, Baniyas and Bohras dominating local trade. The earliest examples of “native” public writing — like signage — are in Gujarati. Bombay was also where Gujarati printing and journalism were born. The Bombay Samachar, a Gujarati paper established by a Parsi in 1822, is Asia’s oldest continuously printed newspaper. Linguistic nationalism Make no mistake — violence is a logical expression of linguistic nationalism, not an unexpected deviation from its chartered course towards cultural homogenisation and the erasure of histories of cultural interactions. By politicising linguistic identities, communities are compelled to compete against one another to secure social and political capital for themselves, vying for limited commodities of space and power — something that can all too easily descend into violence.

Given the very nature of linguistic nationalism and how it prioritises the needs of one linguistic community over others while guaranteeing them state support, these clashes are as a rule asymmetrical, with minorities bearing the brunt of institutional violence and apathy.

For those familiar with Tamil Nadu politics, this antipathy towards Telugu is not exactly new. The nationalist Naam Tamilar Katchi (‘We are Tamils’ Party), with its calls for the state’s political power to be limited to those it deems “true Tamils”, has singled out local Telugu-speaking castes in its opposition to “outsiders”. These numerous Telugu-speaking agricultural and artisanal communities migrated south beginning from the Vijayanagara period forming an essential part of Tamil Nadu’s social fabric; late 19th-century British census figures record “substantial Telugu-speaking minorities in the Tamil districts of Coimbatore, Madurai, Salem, Tirunelveli, Chingleput, and Tiruchirappalli." [caption id=“attachment_8280251” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Defaced Tamil signage in Melukote, Mandya district, Karnataka, a Vaiṣṇava center home to many Tamil Brahmins[/caption] In the wake of the contentious Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, ethnic tensions — intimately tied to linguistic identities — have been brought to the fore with a renewed urgency. Now more than ever, active resistance to the forces of muscular linguistic nationalism is imperative, requiring keeping an eye out for its telltale signs, of which linguistic marginalisation is but one. Although the dangers of communal nationalism have been belatedly recognised, linguistic nationalism has thus far escaped greater scrutiny by civil society, an oversight that does not bode well for India. As Nair writes, incidents of linguistic violence often feature “the coalescence of multiple agendas”, with only a thin veneer of linguistic protection for legitimacy. Recent events in Assam should drive this point home. After all, the forces that drive linguistic marginalisation closely mirror other processes of social marginalisation; linguistic nationalism is to be watched and kept in check too. * Karthik Malli is a freelance journalist who writes on the intersection between language, history, and culture

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)