The top Chinese leaders and experts meet annually during the summers at the seaside resort of Beidaihe. The legendary Mao Zedong started this tradition of summer retreat apparently as early as 1953. But this meeting that is believed to happen usually in the first two weeks of August is not a summer camp. Though the meeting is informal and secretive and the agendas discussed are not publicly disclosed, the economic policy direction and reform initiatives would have dominated the discussions, keeping the recent trends of the Chinese economy under consideration.

China’s weakening household spending and the economic slowdown are a concern of investors as well as Chinese policymakers. China’s growth in the second quarter of 2024 is below the expected rate of 5 per cent. The Chinese economy grew at a rate of 4.7 per cent year-on-year (YoY) in the Q2 2024. The same was 5.3 per cent for the first quarter of the present year — marginally up from 5.2 per cent in the Q4 2023, though higher than the market expectations — only to have the weakest yearly advance since Q1 2023 in the next quarter.

On August 5, the Chinese government outlined a 20-point plan to stabilise and boost the economy. Measures included in it aimed at encouraging consumption — on a wide range of goods and services, including new energy vehicles, home appliances, electronics, catering, and tourism; encouraging private investments; stabilising the property market; unveiling a package for tax relief measures for small businesses; and boosting consumption in rural areas. Whether these measures would be enough remains to be seen, with experts demanding more to stimulate consumption.

China’s economic might is its biggest power — from domestic promise to international commitment — that forms the clout of Beijing’s red aristocracy, which relies on the promise of sustained economic growth. Any compromises in this regard baffle policymakers in China.

Impact Shorts

More ShortsIn fact, the third plenary meeting of the Communist Party of China, which took place from July 15 to 18, 2024, focused on economic reforms, including market mechanisms, fiscal and taxation reform, and de-leveraging the real estate sector. The meeting also discussed social policies, including strengthening social safety nets, promoting consumption, and addressing the urban-rural income gap.

The Chinese economy has been facing several challenges, apart from the GDP growth not being able to match expectations. That includes:

Trade tensions with the US and West, on the issues of tariffs on Chinese goods — recently China dragged the European Union to the World Trade Organisation over tariffs on electric vehicles.

Debt crisis in the corporate sector and local governments, one can refer to IMF reports for this.

Pricing of the property market bubble, in the first quarter of 2024 the real estate investment was 2.2 trillion RMB ($303.5 billion), a year-on-year decrease of 9.5 per cent.

Also, the manufacturing sector, one of the biggest strengths of China, is suffering.

Apart from this there are several other challenges, that include an ageing population — shrinking of workforce and increase of dependents; reform required in China’s state-owned enterprise system; and competition with the West in emerging technologies – particularly in areas like semiconductors and artificial intelligence.

Also, there looms a threat of the middle-income trap. In the recently released World Bank’s report, World Development Report, it was estimated that China might take more than 10 years just to reach a quarter of US per-capita income. Experts believe that China might end up falling into the middle income trap — a situation where the countries growing wealthier and reaching 10 per cent of the annual US GDP per capita hit a ‘trap’ whereby their growth becomes stunted, restraining the economy from reaching the status of a high-income country.

China became a lower-middle income country by 1997 and an upper-middle income country by 2010, but experts believe that China needs a robust sustained growth rate of 6-7 per cent over the decade to avoid falling into the middle income trap and achieving the high income status.

South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore spent 23, 27, and 29 years, respectively, as middle-income economies before moving up to the upper-income level, so by clear trends, it’s the time China should have tightened its belt for achieving the high-income country status.

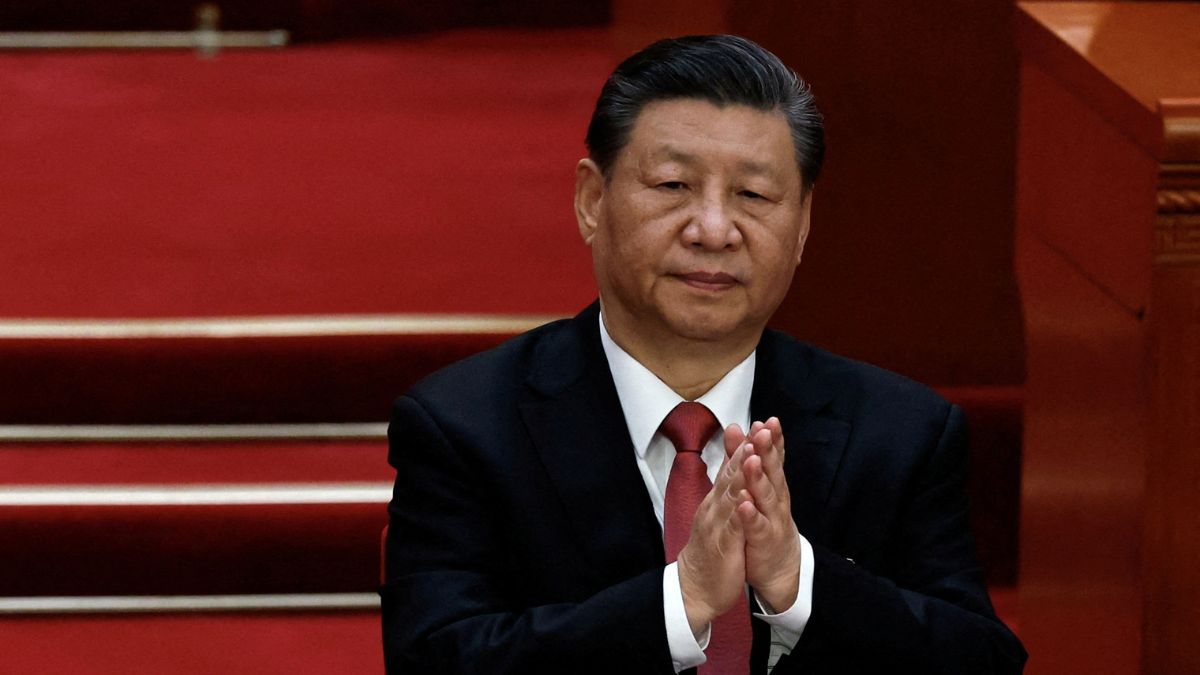

The Chinese economy is undoubtedly an economic miracle. This remains a big factor backing the authoritarian rule of the Communist Party of China. The promise of economic prosperity to its population provides legitimacy to the hierarchical rule and remains the backbone of the ‘Chinese dream’. These are the years that will contribute to the legacy of Xi Jinping, something Chinese paramount leaders have been most concerned about. So while the ivory tower CPC leadership can afford to ignore issues of human rights, economic growth is certainly not the sphere where leniency is affordable.

Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.

)