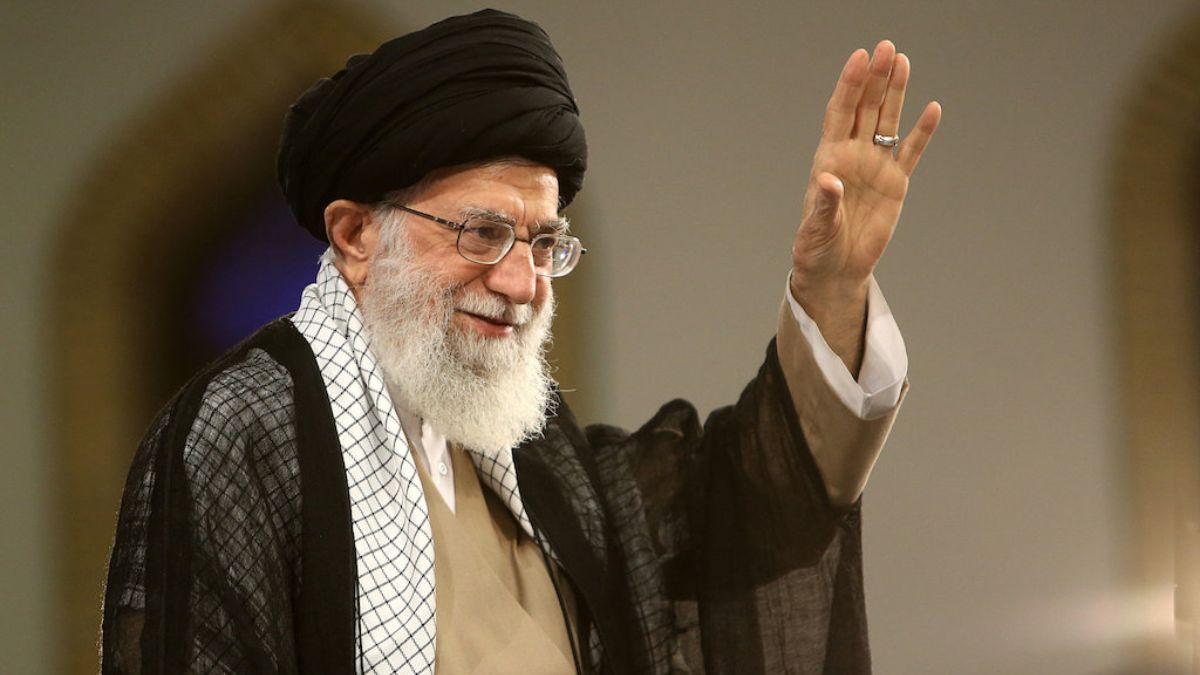

It is indeed ironic that Iran’s Supreme Leader would be “worried” about the treatment of minorities in India, much less compare it to Gaza and Myanmar. This is a nation where religious minorities, including Baháʼís, Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians, face systemic discrimination and persecution. The Baháʼí community, in particular, has been subject to decades of oppression, with their leaders routinely arrested, their properties seized, and their religious practices suppressed.

Conversion from Islam to other religions is punishable by death, and non-Muslims are routinely treated as second-class citizens. While the Supreme Leader criticises India, his own nation has made life unbearable for its minorities, turning religious persecution into a state policy.

The treatment of ethnic minorities in Iran is no less brutal. The Kurdish, Azeri, Baluchi, and Arab populations, among others, face routine discrimination and economic marginalisation. The Iranian government systematically denies them cultural and linguistic rights, often punishing expressions of ethnic identity as acts of rebellion. Kurdish activists face execution, while Baluchi regions remain severely underdeveloped, with high levels of poverty and state neglect.

Iran’s treatment of women is another grotesque example of state repression disguised as religious morality. The mandatory hijab law, which forces women to cover their hair in public, has been a point of contention for decades. Women who refuse to comply face harassment, imprisonment, and even torture. The recent protests, where women courageously burned their hijabs, have been met with violent crackdowns. Iran’s morality police continue to terrorise women into submission, and the regime’s obsession with controlling women’s bodies has turned half of its population into prisoners of a medieval ideology.

India promptly and rightly responded to the unsolicited advice. “We strongly deplore the comments made regarding minorities in India by the Supreme Leader of Iran. These are misinformed and unacceptable. Countries commenting on minorities are advised to look at their own record before making any observations about others,” the Ministry of External Affairs stated. It was a clear and firm message to Tehran: India does not need lectures on minority rights from a regime that tramples on them daily.

Impact Shorts

More ShortsMoreover, contrary to the distorted narratives pushed by certain media outlets, Muslims in India are not facing any form of apartheid or genocide. There are fundamental misconceptions regarding the position of Muslims in India. Unlike Iran, which is a rigid theocracy, India is a vibrant parliamentary democracy. The Indian Constitution does not classify citizens based on religion, ensuring equality for all. At the social level, Muslims are not merely a minority; they are the second-largest community in the country. In fact, Muslims in India enjoy perks and privileges that are arguably unmatched in any other democracy. If anything, they are one of the most politically and socially pampered minorities in the world.

After a bloodied partition of India and Pakistan along communal lines, Pakistan became a Muslim theocracy, while India chose the path of a secular, democratic republic. But even within this democratic framework, Muslims were allowed to retain their personal laws, effectively creating a small theocracy within a secular system. India houses a Ministry of Minority Affairs, specifically tasked with promoting minority welfare, including initiatives tailored for Muslims. Minority institutions thrive, and affirmative action programmes benefit Muslims across various sectors. Prominent Muslims in India—from the armed forces to the highest political offices, from renowned academics to Bollywood stars—enjoy widespread success and respect. India does not need to be schooled by Iran on how to treat its citizens.

There is another dimension behind Iran’s irksome comments against India, and something more sinister might be at play. Since the onset of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the United States imposed harsh sanctions on Russia in an attempt to cripple its economy. However, India did not halt its purchase of Russian oil, much to the visible dismay of the West. The backlash was so intense that India had to push back diplomatically, with External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar visiting international forums to explain that India’s energy security, coupled with its fragile economic base, left little room to engage in moral debates over oil supplies. Eventually, India’s position was accepted, if not embraced, in international discourse.

In stark contrast, after the US sanctions on Iran, India did stop buying Iranian oil, which was a severe blow to Iran’s already struggling economy. For years, Iran had been one of India’s top three oil suppliers, with energy forming the backbone of India-Iran economic ties. Indian refineries, such as the Mangalore Refinery (MRPL), were specifically designed to process the heavy crude that Iran supplied. The cessation of these imports not only hurt Iran’s economy but also strained diplomatic ties between the two nations.

The numbers reflect the economic fallout. India-Iran bilateral trade plummeted by a staggering 90 per cent over the past three years due to US sanctions. According to the Department of Commerce of India, bilateral trade fell from a high of $17 billion in 2018-19 to just $2.33 billion in 2022-23. That’s an 86.29 per cent decline, with India’s exports to Iran standing at $1.66 billion, while imports from Iran amounted to a meagre $672.12 million. The previous fiscal year (2021-22) saw an even lower trade volume, with bilateral trade hitting a low of USD 1.94 billion. The data for April-July 2023 shows a further decline, with total trade decreasing by 23.32% compared to the same period the previous year.

This economic strain is likely one of the reasons for Iran’s irresponsible comments about India’s treatment of minorities. However, this needs to be understood that there is a significant difference between India’s relationships with Russia and with Iran. Diplomatic and trade ties with Russia go back to the very inception of the modern Indian republic. As Kabir Taneja, a Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation, notes, “India’s military preparedness today, especially in the wake of heightened tensions with China following the 2020 border clashes, relies heavily on close cooperation with Moscow.” Russia is India’s primary defence supplier, offering critical technologies, including nuclear submarines, which no other country currently provides to New Delhi. This deep-rooted military and technological relationship is crucial for India’s national security and strategic autonomy.

Moreover, there are practical challenges in importing oil from Iran that do not exist while trading with Russia. The logistical hurdles and the geopolitical risks involved in continuing economic engagement with Iran, given the ongoing U.S. sanctions, make the relationship fraught with complications.

Above all, it is the prerogative of any nation to take actions that prioritise the well-being of its own people. India’s decision to stop importing Iranian oil was a pragmatic choice driven by its need to balance global diplomatic pressures with its own economic and security interests.

It is also inaccurate to claim that India has made no efforts at all to maintain trade relations with Iran. Even in the face of US sanctions, particularly under the presidency of Donald Trump in 2018, New Delhi and Tehran attempted to preserve the oil trade through various strategies. For instance, India submitted its payments to a bank account in Kolkata, which eventually accumulated over $4 billion. However, accessing these funds became increasingly difficult for Iran as global pressure mounted on Tehran to agree to terms that would constrain its nuclear ambitions. By 2015, the avenues for India to pay Iran for oil had become nearly non-existent, as India, being a signatory to several international financial treaties, found itself caught between compliance with global transparency efforts and maintaining a critical trade relationship with Iran.

In more recent developments, in May 2024, India signed a 10-year deal with Iran to further develop the strategically crucial Chabahar port. Despite US warnings about the potential risks involved in conducting business with Iran, India stood its ground, backing the agreement and emphasising its regional benefits. Responding to Washington’s concerns, Jaishankar pointed out that the US itself had previously appreciated the strategic relevance of Chabahar. He reiterated that a long-term partnership with Iran was necessary to improve the port’s operations and that its success would be a boon for the entire region.

This brings us to a perplexing question: why, at such a crucial time, would Iran’s top leadership choose to provoke India? Why would Tehran risk jeopardising a significant project like Chabahar, which has the potential to reinvigorate not just Iran’s economy but that of the entire region?

Is it an attempt to placate the hardline conservative factions within Iran, now that the Ayatollahs are losing their grip over the increasingly disenchanted population? Or, is it a desperate bid by a Shia-majority nation to prove its Muslim credentials to the wider Sunni world? Did the “Messiah of Muslim Ummah” forget to mention the suffering of Uyghurs because China is currently the top buyer of Iranian oil despite US sanctions? Above all, would Iran be willing to sabotage its own national interests in hopes of gaining relevance in this imaginary unity of the Muslim Ummah?

These are hard questions that Iran will have to answer soon enough. While Tehran seeks to hold on to its ideological posturing, it risks alienating one of its most important allies. India, meanwhile, will continue to focus on what truly matters—its strategic and economic security, driven by pragmatism rather than the empty rhetoric of a fading theocracy.

The writer takes special interest in history, culture and geopolitics. The views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)