In 1948, when raiders from the newly formed state of Pakistan decided to attack Kashmir, the focus of the government in Delhi was to save the valley. However, Pakistan’s sights were also set on Ladakh, believing that capturing the thinly held and vast Himalayan plateau could leave India vulnerable to Pakistan’s occupation of territory close to the Indian heartland.

It is pertinent to mention that the complete focus on Kashmir at that time could have inadvertently led to a possible loss of Ladakh — the outcome of which may not have been interpreted in its exact terrifying context. The loss of Ladakh was more real than Kashmir. It was the courage of a few good men that saved Ladakh. Among the few good men was Sonam Norbu, a Britain trained local Ladakhi engineer who was brought in from overseas to build a makeshift airstrip in an inhospitable terrain in Leh so that Indian troops could arrive. Ladakh would have been severed from India if the helipad wasn’t made in time, or the thirty odd Indian army troops and the band of locals (led by a 17 year old volunteer) together hadn’t protected the region.

Seventy Years Later… Another Disaster Stares

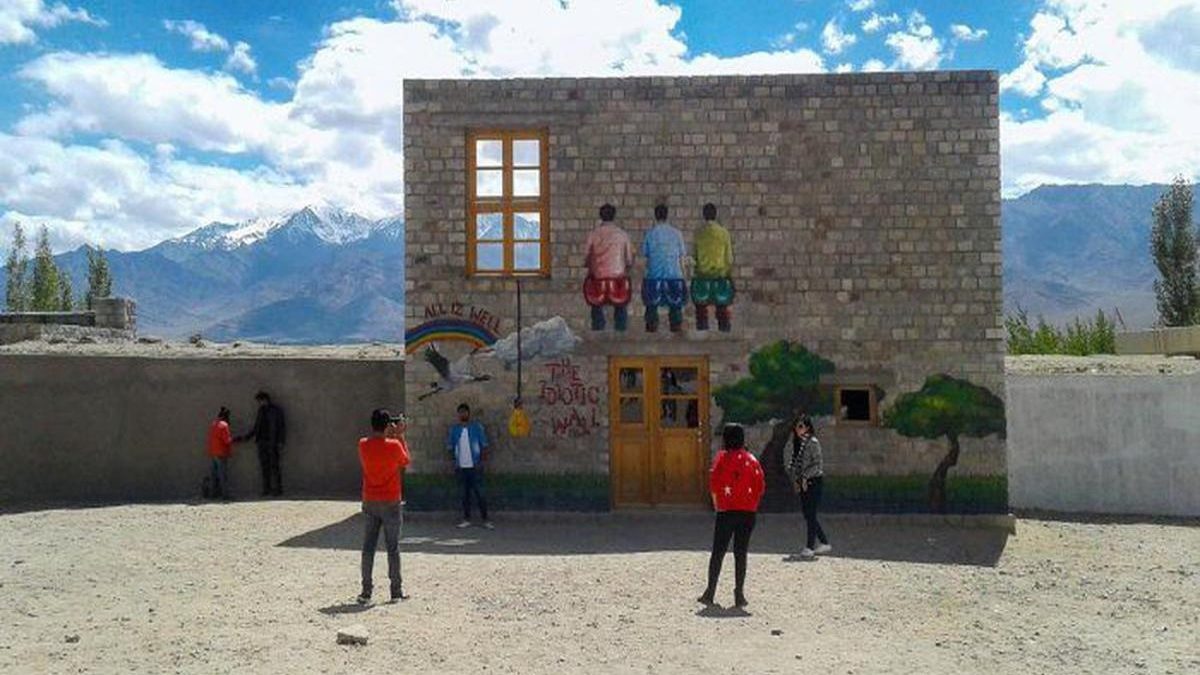

Seventy years later, as several other issues occupy our attention, the issue of consistent ecological damage in Ladakh and its fallouts escape our strategic consciousness. Sonam Wangchuk’s recent fast holds significance in that regard. In Leh, the airport came before the road, says Ambassador P Stobdan, a prominent strategic affairs expert. That airport, built in 1948 has turned into Leh’s gateway to tourism. In recent years, given its direct connectivity of flights from major destinations, Leh has turned into a must-see for Indians aspiring to travel to the Himalayas and trek on snow-laden roads a couple of flying-hours away from home. In 1974, 527 tourists visited Leh. Fifty years later, it has become much easier to travel. Visitors have increased to close to half million.

As one of the fastest growing tourism destinations, Ladakh has witnessed rapid economic progress. This has resulted in the rise of local businesses that cater to tourists, and the key impact has been in the real estate. When I visited Leh last year, I noticed that the outer perimeter of the capital seems to increase with each visit. There is much construction across the land — many of them being small hotels. From around 20 hotels throughout Ladakh in the 1980s, there are over 700 now, with most of them in Leh. “Almost 75% of people in Leh and the surrounding areas now run either a hotel or a guest house from their property,” says Chewang Norphel, a Ladakh local – in an environmental magazine, ‘The Third Pole’. Norphel invented the technique of creating artificial glaciers in the region.

Unchecked tourism has also resulted in excess garbage, noise and air pollution that could create a mess in the future. A proliferation of tourists and hotels has meant more consumption of water. According to the Ladakh Ecological Development Group (Ledeg), an average Ladakhi consumes 21 litres of water per day, while a tourist needs almost three times as that. At an high altitude of over 10,000 feet altitude, Ladakh lies in the rain shadow region of the Himalayas where less rains, mainly in the form of snow, sustains the region. But the increase in footfall and consumption has led to higher water demand from tourists in hotels. Hotels have had to dig borewells to extract groundwater, which destroys the fragile water table.

Impact Shorts

More ShortsFor instance, Leh, the capital, town used to get its water supply from glaciers. But over the years, the hotels have been forced to dig for water, draining the already reduced water table. It has been reported in the media that water shortage is forcing locals to leave their generational homes and give up their agrarian-based economy.

Lessons from Lakshadweep

There is a possible lesson from another region — that is far away but bears comparable ecological vulnerabilities alongside pressing tourism traffic. Lakshadweep is an archipelago of thirty six islands off India’s southwestern coast on the Arabian Sea. Lakshadweep is surrounded by rare coral reefs, marine biodiversity and a scenic beauty that could have been swamped by unchecked tourism. To protect its ecology, there is a policy of restrictions for tourists in place.

Lakshadweep is also protected because of the strategic importance of the islands that serve as a vital cog of India’s control of the oceans and sea lanes of communication that enable the continuation of trade movements on sea without disruption. The islands are also a strategic base for the Indian navy and its maritime drills in the Arabian Sea.

Lessons to Protect Ecology

Countries have introduced high tourism taxes to ensure tourists pick up the tab for the maintenance of tourist hotspots. Recently, Scotland introduced taxes, thus adding to the list of countries taxing tourists.

Countries such as Bhutan, Japan, France, Switzerland, Germany, Italy and others already have such taxes in place. Bali is a recent destination that has introduced tourist taxes this year (2024) from February onwards, with an aim of reducing traffic congestion and waste management pains.

Hawaii is a strategic location for the United States alongside being a tourist destination. Recently, Hawaii introduced a climate impact fee on tourists to protect the local sentiments and environment. “I believe this is not too much to ask of visitors to our islands. Hawaii’s natural resources, our beaches, forests, and waterfalls, are an essential part of our culture and our way of life,” said its Governor Josh Green during his 2024 State of the State address.

Ecology as a Need and Necessity

The Indian Himalayan Region has about half million tourists each year, putting strain on limited resources, impacting waste management, water resources and biodiversity. The importance of controlling tourist footfall has been reiterated in a five-set report of the NITI Aayog emphasising the need for sustainable development in the region.

On the strategic front, the Himalayas form a perimeter fence for India, covering about 500,000 kilometres across ten states in an arc that stretches from the west to the east of the country’s borders. Kashmir and Ladakh to the north and the northeastern states can be vulnerable to Chinese interference.

Sunil Raman, a former BBC journalist wrote a few years ago about China’s ploy of invisible incursion where ideas, language and culture are used as weapons to gain a foothold in India’s vulnerable areas. In that context, he points out to an expanding spiritual influence of Tibetan Buddhism from China over the Ladakhi version. He wrote about the threat of a possible takeover of Buddhist institutions by Chinese Tibetans aside from sectarian tensions among Buddhist sects.

Both Pakistan earlier and now China have had an ambitious eye on Ladakh – but have been warded off militarily several times. Ignoring ecological imbalances and resulting local difficulties could provide an opening for hostile neighbours. Monitoring pollution levels, levying taxes on usage of local resources alongside the need for a transparent and productive discussion on the pressing ecology-related issues of Ladakh ought to be seen from a judicious standpoint, given that the anxieties and tribulations of locals cannot be left unattended and exposed in an area of vital strategic importance.

The writer is the author of ‘Watershed 1967: India’s Forgotten Victory over China’ and ‘Camouflaged: Forgotten Stories From Battlefields’. His fortnightly column for FirstPost — ‘Beyond The Lines’ — covers military history, strategic issues, international affairs and policy-business challenges. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views. Tweets @iProbal

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)