The year was 2013. The then Chief Minister of Gujarat, Narendra Modi, had emerged as the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) prime ministerial candidate. There were murmurs of discomfort within certain quarters of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA). In Bihar, Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, a long-time partner of the BJP, saw Modi as a threat to his own political ambitions.

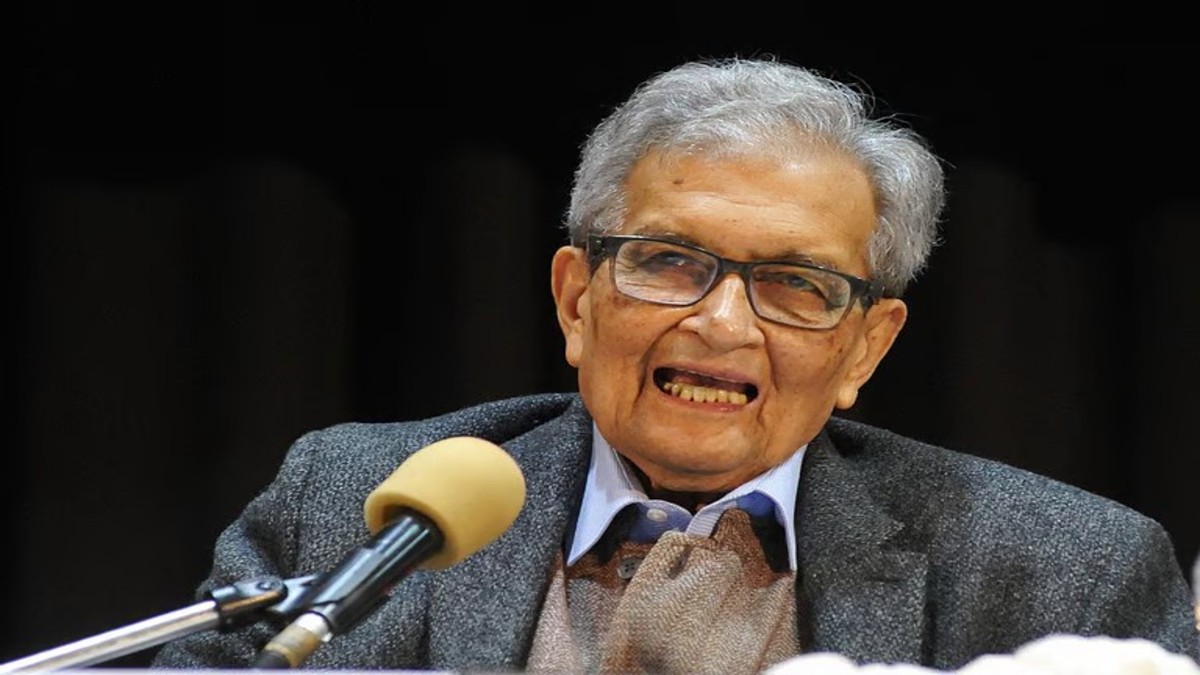

During that time N K Singh, an influential bureaucrat-turned-politician, hosted a dinner in Cambridge. Among the distinguished guests was Nobel laureate Amartya Sen. According to Sankarshan Thakur’s book Single Man: The Life and Times of Nitish Kumar of Bihar, Singh posed a pointed question to Sen:

“What, Sir, do you think are the options before Nitish Kumar?”

Sen’s response was sharp and layered with meaning: “Nitish Kumar has several options, but only one honourable one.”

The “honourable” option was for Nitish to break away from Modi and the BJP. Within days, the Janata Dal (United) severed its 17-year-old alliance with the BJP — a move that reshaped Bihar’s political dynamics and the NDA’s future.

Over the years, much has changed in Bharat’s politics. Nitish Kumar has shifted political sides multiple times, eventually returning to Modi’s fold. But Amartya Sen’s revulsion for Modi and his brand of politics remains strong.

Fast forward to August 2025. Amartya Sen has once again stirred the political discourse, this time over the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls. In his latest remarks, Sen has accused the Modi government of risking the “disenfranchisement of poor and marginalised communities” by allegedly imposing strict documentation requirements and rushing the revision process. He has warned that Bharat’s democratic fabric could weaken if such exercises were handled hurriedly and insensitively.

Impact Shorts

More ShortsHowever, this criticism is deeply contested. SIR isn’t a new initiative, after all. Periodic revisions of electoral rolls have been part of the country’s democratic process for decades. Even the claim that this particular exercise was rushed to influence the Bihar elections doesn’t hold up under scrutiny. In fact, in the last such exercise over two decades ago, electoral roll revisions were completed in a shorter timeline than the current one — and that too at a time when the country had far fewer technological and logistical capabilities. With modern digital infrastructure, the process is arguably faster, cleaner, and more robust than ever before.

The fact is that SIR is an electoral process that every democracy worth its salt pursues periodically. It strengthens the country’s democratic process by ensuring that only genuine voters are on the rolls. By opposing SIR, Sen seems to have aligned himself with forces that are working overtime to delegitimise Bharat’s democratic institutions.

Sen’s stand on SIR could be analysed through his lone-term ideological positioning. For decades, Sen has been a vocal critic of Narendra Modi. This has influenced his interpretation of political events — every issue becomes a war against Modi.

Amartya Sen’s anti-Modism has become an ideology in itself. Everything else is moulded to suit this worldview. This explains why, in 2014, he “flew from Boston to New York, New York to New Delhi, and New Delhi to Calcutta and took a car to [his] village to vote against Mr Modi’s BJP candidates”, as he confessed in an interview in 2017. This candid admission reveals that Sen’s stance on SIR isn’t an isolated incident — it’s consistent with a long-standing political bias.

Take his oft-repeated argument on the 2014 Lok Sabha elections: He questioned Modi’s prime ministerial legitimacy because “69 per cent of Indians didn’t vote for him”. What he mischievously ignored was that if Modi received 31 per cent votes, it didn’t necessarily mean the remaining 69 per cent people were against him. Even if one accepts this argument, it only exposes the hypocrisy and double standards of Sen and other such intellectuals. After all, such statistical arguments were never invoked in the past. Not when Jawaharlal Nehru, in the first Lok Sabha elections in 1952, saw more than 55 per cent people opposing him. (The Congress, in the 1952 general elections, got 44.99 per cent votes.) Similarly, at the height of her popularity in 1971, Indira Gandhi received only 43.68 per cent votes.

Yet Sen and his peers — Kaushik Basu, Ashutosh Varshney, and Raghuram Rajan, among others — never invoked such statistical arguments before 2014. This selective use of data fuels accusations of hypocrisy and double standards.

There is a clear pattern in the shifting positions of Sen and his ilk: From questioning the legitimacy of the first-past-the-post electoral system to questioning the electoral system itself.

In the past decade, if there is one consistent trend in Bharatiya politics, it’s that the Modi-led BJP has been further entrenching its hold over the masses: The BJP’s vote share rose from 31 per cent in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections to 36.56 per cent in 2024. As an alliance, the NDA’s share grew from 38.5 per cent to 42.5 per cent in the same period.

There is another reason for Sen’s overwhelming rage against Bharat: the growing Hindu-ness of the masses, their newfound confidence, and pride in Sanatana heritage. He had always imagined Bharat as a divided house, bickering endlessly. In an interview with The New Yorker on October 6, 2019, Sen said, “India is a country of more than a billion people. Two hundred million of them are Muslim. Two hundred million of them are Dalit, or what used to be called untouchables. A hundred million are what used to be called scheduled tribes, and they get the worst deal in India, even worse than the Dalits. Then there is quite a large proportion of the Hindu population that is sceptical.”

Sen and his ideological comrades simply cannot accept the reality of Naya Bharat. In their rage and desperation, they seem to be giving up on the prospect of change from within. There is a growing clamour for Bangladesh-like regime change in certain quarters. Sen may not have publicly advocated this, but his ideological brethren have no qualms discussing it in hushed voices.

Anyone who has visited Bihar, Bengal, and Assam, especially, would easily discern this outside element in the electoral system: The presence of illegal Bangladeshi immigrants. The SIR exercise seeks to remove them from the voter list.

Sen’s opposition to SIR, thus, wittingly or otherwise, may help in subverting the established democratic mechanism to implant a democracy of his ideological choice — a democracy where the will of the people remains subservient to the will of the intellectual elite.

One of the strongest criticisms levelled against Amartya Sen is his selective outrage. While he spares no effort in criticising Bharat’s electoral practices, he remains largely silent on similar — and harsher — policies in the United States, his adopted home. For example, US states regularly purge voter rolls, introduce strict ID laws, and restrict voting rights — often disproportionately affecting minorities. Yet, Sen’s interventions on such matters have been limited, if not entirely absent.

He remains silent on how the US administration has deported illegal immigrants, including Indians, with handcuffs and other humiliations. His liberal conscience isn’t perturbed by the Trump government’s ongoing war against academia, waged in the name of fighting wokeism. His stance of loudly lecturing the country of his birth while staying conspicuously silent on the excesses of the country where he chooses to reside is both opportunistic and hypocritical.

In the end, it’s obvious that Amartya Sen’s battle — and also that of his so-called liberal comrades — is less about principles and more about their deep-seated dislike for Naya Bharat in general and Modi in particular.

If democracy has to be defended, it demands consistency — something conspicuously missing in Sen and his followers. The man who once advised Nitish Kumar on choosing the “honourable path” now faces accusations of choosing a dishonourable one himself — disowning and dismissing the will of Bharat’s people in favour of a narrow ideological and opportunistic worldview.

Not at all a good idea, SIR jee!

Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.

The author is Opinion Editor, Firstpost and News18. He can be reached at: utpal.kumar@nw18.com

)