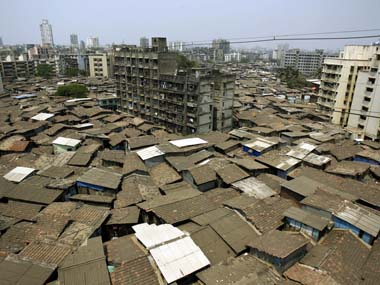

by Sujit Kelkar In September 2009, soon after Mumbai’s Human Development Report dispelled the myth about Dharavi being Asia’s largest slum by pointing out that Karachi’s Orangi Township had surpassed it, a cartoonist was appropriately sarcastic: while reading about this development in a newspaper, a worried politician tells another, “I told you Pakistan is our biggest threat!” The real concern of the `saviours’ of Dharavi’s poor (more accurately, the electoral constituency) and why, for some, it is necessary for it to remain a slum pocket does not often get told with such sharp understated humour. Let’s consider why Dharavi has been in the news of late and whatever happened to the grand plan of redeveloping it into a plush financial and residential hub for, largely, those who can afford it. [caption id=“attachment_370211” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  A general view of Dharavi. Reuters[/caption] After wasting eight years and at least Rs 50 crore only in its preparation, the ambitious Dharavi Redevelopment Project (DPR) finalised in 2004 is, optimistically speaking, moving at a snail’s pace to get out of the mess in which it was stuck owing largely to political and administrative apathy. Last month, Chief Minister Prithviraj Chavan ordered the preparation of a detailed list of eligible slum-dwellers, apart from launching the search of a genuine software company to collect and assess data. At a review meeting of the plan, Chavan set the 1995 electoral roll as the basis for drawing a list of slum-dwellers eligible for housing in just one of the five sectors, which is being developed by the sole nodal agency, Maharashtra Housing and Development Authority (Mhada). While directly seeking the help of a genuine software firm to collect and assess the data, so that a comprehensive database of the project can be prepared, Chavan said top priority should be given to this work. “If needed, a separate mechanism can be set up to complete the work in a time frame,” he is reported to have said. Details of the area of land belonging to the Centre, the number of slums on reserved land and the total area of land available for free housing were also sought apart from issuing directives for an urgent appointment of a project advisor for the first building to be redeveloped by Mhada. In other words, more than a year after MHADA was appointed as the nodal agency for the project and six months after the Development Control Regulations (DCR) were finalised, the government does not even yet have the basic data about rehabilitation and redevelopment in a relatively small area of Dharavi. Considering the fact that the approach to redevelopment changed at least four times in the previous eight years, which also witnessed the rule of three chief ministers in two coalition governments, the lack of urgency in official quarters is appalling. The fact that the integrity of even this miserably slow process is related directly to the time available with the man leading the charge of Maharashtra, which many optimists believe is only until the next state elections in 2014, makes one wonder how much hope to invest in it. For India’s flagship slum redevelopment project, which is also a veritable gold mine for profiteers with the spoils ranging between the conservative estimate of Rs 26,000 crore and market estimate of nearly Rs 50, 000 crore for the chosen area of nearly 380 acres, to make any real progress, a strong political and administrative will combined with people-first approach is of utmost importance. This, of course, is necessary if one even considers that public land is meant for the benefit of the people at large, especially those deserving and in desperate need of the same instead of a coterie of builders, politicians and NGOs. The fear about the DPR, however, is that the man guarding the city’s 380 acre gold may not be able to hold on to it for too long.

India’s flagship slum development plan is still stuck in political and bureaucratic dilly-dallying.

Advertisement

End of Article

Written by FP Archives

see more

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)