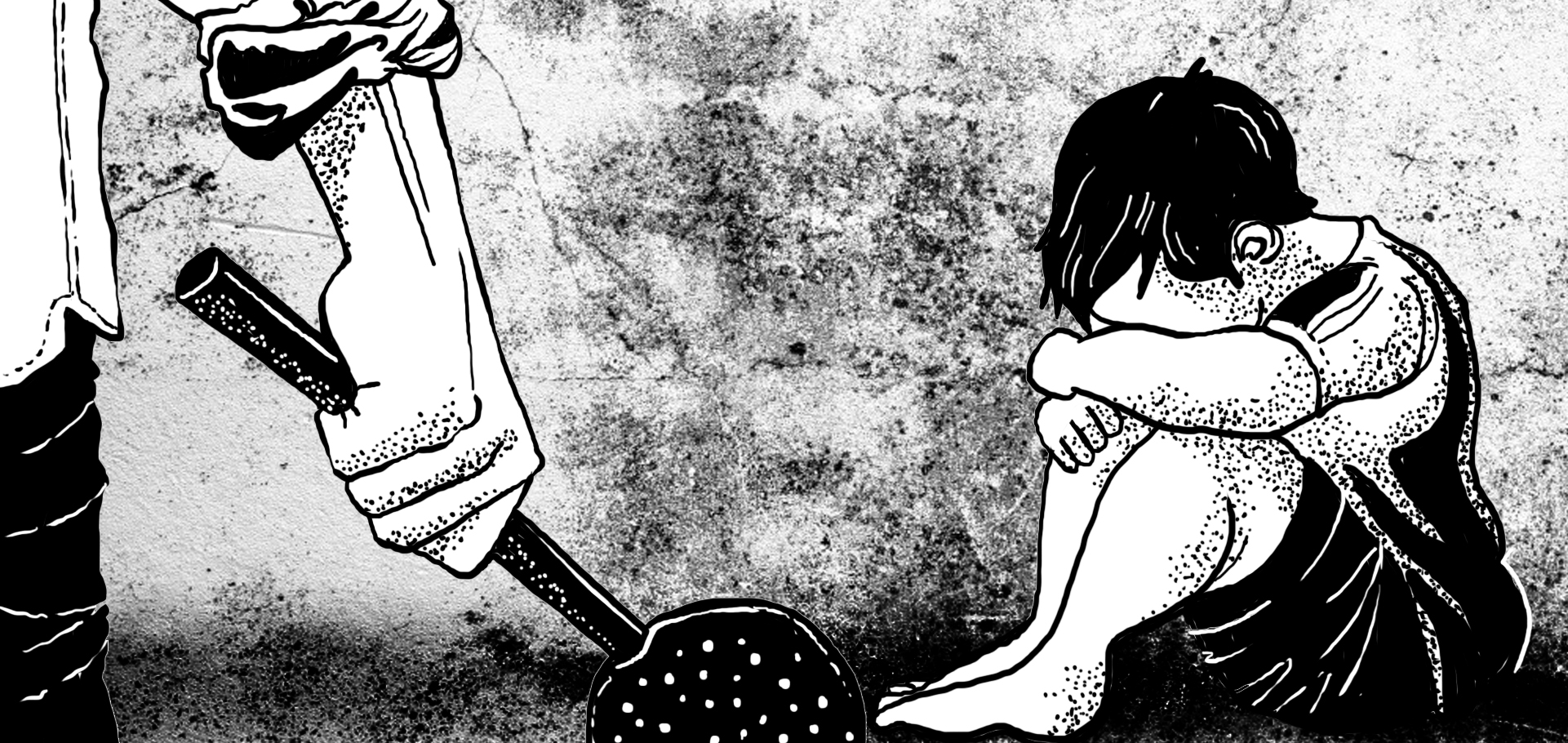

From the first day that ‘M’* came to the children’s home with his mother, it was clear that he had witnessed a lot of violence and trauma. The 10-year-old boy was attention-seeking and belligerent, and he often picked up fights with other kids. Often, in the middle of a conversation, he would abruptly say, “Mujhe paagalkhaane bhej do; mujhe marna hai.” (Send me to an asylum; I want to die.) His story, and that of his family, unfolded over the next month. The boy’s mother had lived at the children’s home for girls a decade ago. In September, she now returned to Prayas JAC Society’s office as an adult, seeking shelter and support. She had suffered vicious abuse at the hands of her husband, and so did her three children. On one occasion, M’s father scalded him with a hot steel utensil so severely that he could not walk for months. On several occasions, the father got him to steal from other people’s houses. It was under these circumstances that M had been arrested for a brief while by the police, at an age when he could barely understand the consequences of his actions. Luckily for the young boy, he was let off.

The narrative around juvenile offenders has been overstating that poverty and deprivation are the reasons for such crimes.

For instance, S* — a 16-year-old boy from a relatively affluent family — got involved in a murder case after his family got into an argument with another family with whom they had a business partnership. In another instance, X* — a 15-year-old boy — was involved in a case of kidnapping and murder after a fight with another schoolboy turned ugly. Earlier, X had been beaten up severely by the same boy, due to which he suffered multiple fractures and was hospitalised for 2-3 months. He later took his revenge by stabbing the boy to death, after which he came into the clutches of the law.  These are cases where one cannot come to easy conclusions — whether by way of condemning the ‘criminal tendency’ of the child, or by way of attributing the crime to ‘circumstances’. Around a year ago, the country was preparing for a stormy Winter Session of Parliament in which, among other things, the proposed law on juvenile justice was passed. The Juvenile Justice Act, 2015 is now a reality. But now, there is a need to take a hard look at the law, in a way which goes beyond the 16 December 2012 Delhi gangrape. *Names have been changed to protect identity The author works with Prayas JAC Society, an organisation headquartered in New Delhi, that works on child rights

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)