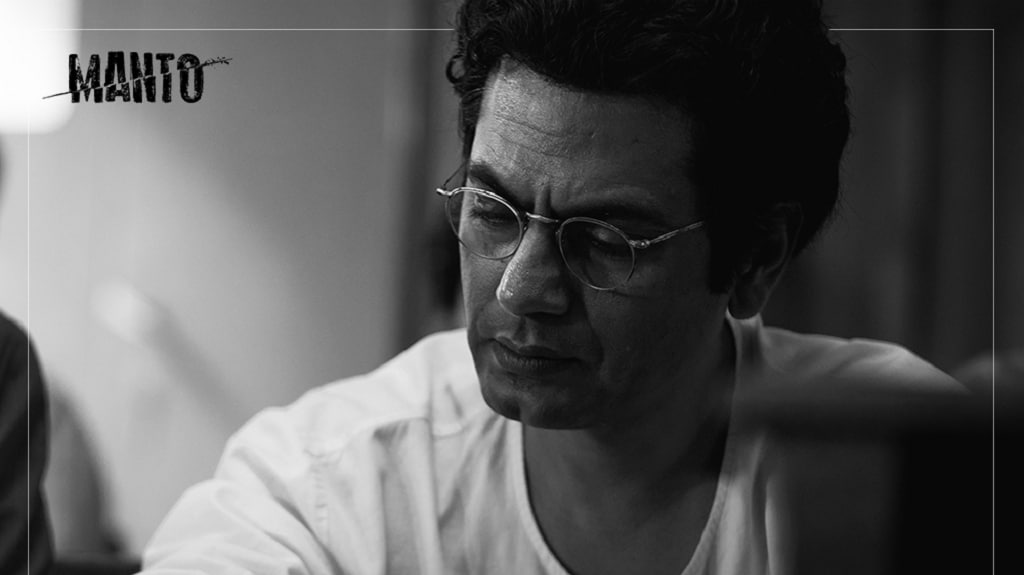

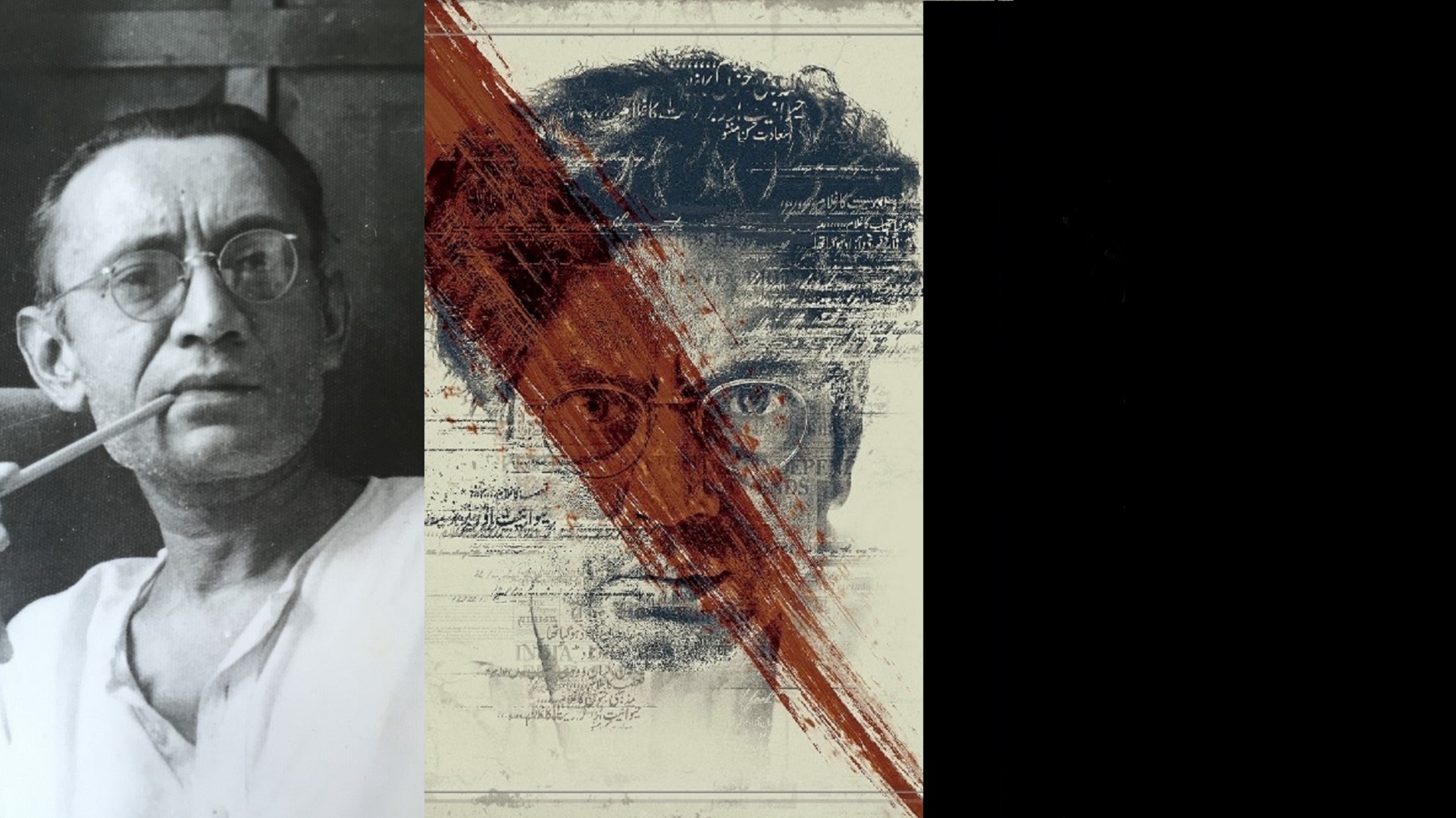

“In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful Here lies Saadat Hasan Manto, and with him lie buried all the secrets and mysteries of the art of short-story writing… Under tons of earth he lies, still wondering who among the two is the greater short-story writer: God or He.” - Manto’s epitaph for himself Over six decades after his death, the literary legacy of Saadat Hasan Manto remains as relevant as ever. Actress-filmmaker Nandita Das’ feature film Manto, which is set to release on 21 September and stars Nawazuddin Siddiqui, is a homage to a writer both celebrated and condemned for his fearless, honest writing.

Das calls Manto a “cosmopolitan Bombaywallah”, referring to the mix of Hindi and English words he used, despite being an ‘Urdu writer’. Manto stayed in Mumbai for a large part of his adult life, moving to Pakistan in 1948 post-Partition. While in Bombay, Manto was both an author as well as a screenwriter for films. In fact, the Hindi film industry greatly influenced Manto’s career — just as it did with many leading Urdu and Hindi writers of that era, including Ismat Chughtai, Krishan Chander, Qurratulain Hyder. These writers also spearheaded the Progressive Writers’ Movement in India. Manto, however, had reservations about the association and chose not to join. Manto and his peers were unafraid of expressing the harsh realities of the times; voices of dissent, of course, have never had an easy time, and Manto found himself facing obscenity charges — both in India and Pakistan — for his stories (including Dhuan, Bu, Khol Do and Thanda Gosht). [imgcenter]

After all, a film on Manto can’t just be about the protagonist; it is as much about the world around him.

Manto’s persona was developed through a detailed understanding of his relationships with others — the other Progressive writers; the film world which featured names like Ashok Kumar, Nargis, her mother Jaddan Bai; his closest friend Shyam; his wife Safia; his sisters; and his children. Das went to Lahore and met Manto’s daughters and other immediate family members (including Zakia Jalal, who was married to his favourite nephew Hamid Jalal). Hamid Jalal was a writer himself and wrote about his uncle; he took care of Manto at a time when alcoholism had reduced him to a state of penury. [imgcenter]

“Haqeeqat se inqaar karna kya hamein behtar insaan banayega? Main likhta hu jo main dekhta hu aur jaanta hu.”

The shoot and location Besides the performances of the main actors, a film like Manto also heavily relies on the mise-en-scène. Recreating the 1940s and incorporating every aspect of that era, including the people, places and events, was a daunting task for the makers of the film. Every detail was taken into consideration, and the list of historical influences is long: Colonial society, the freedom struggle, the Hindi film industry, men of letters, men on streets fighting over Partition and its aftermath.

Rita Ghosh, the art director of the film, explains how they executed the director’s brief and recreated that era. “Nandita’s brief to me was to create the period of the 1940s in a believable manner — the period of pre/post-Partition India. The film includes both the exterior as well as interior as spaces, so for me, it all started from research in terms of the look and feel for two distinct places — Mumbai and Lahore — and accordingly, the look for the architecture, props, costume, colour palettes, lighting, and so on.” She says it was very challenging to shoot at two locations. “Maintaining the continuity was a challenge as we didn’t shoot in the chronological order of the story. Some parts of Lahore were recreated in spaces of Bombay, which included mostly the interiors. A conscious effort was made to show the space when Manto was in Bombay when he was in a better financial state, and when Manto goes to Lahore in 1948, where people were still trying to settle down after the Partition. There was still some tension in the air, there were riots on the streets, houses were burnt down, people were migrating. The detailing involved not only props but also altering the houses, lanes, market, lights and vehicles.”

Nandita Das’ Manto has been extensively shot in various parts of south Mumbai where Saadat Hasan Manto lived: Claire Road, Byculla, Grant Road, and Reay Road station. But because of the changes that the city has undergone since that era coupled with the inaccessibility of Lahore, she had to look for a place which still had the old-world charm, devoid of crowds of people, cables and cars everywhere. [imgcenter]

Attention had to be paid not only to the location but also to the costumes of the people — real and the fictitious. Sheetal Iqbal Sharma who did the costumes for the film takes us through the whole process behind choosing the right texture, style and colour palettes. “The costumes had to reflect the honesty of Manto’s thoughts and convey the gloom, grunge and grittiness of his stories. We delved into the lives of people across the social strata and researched the looks of the 40s extensively. A lot of the information came from meeting families who have still preserved the items from that era as heirloom, souvenirs or just remnants. We were thrilled when Nandita informed us about her associations with the artists and that they have offered to lend us their sarees out of their vintage collectables for us to use in the party scenes. Some of the collectables came from Bina Sarkar, Ila Arun and legendary actor Smita Patil,” says Sharma. The everyday look of the people on the streets had to be devised from extensive research about the dressing sense in those times. Sharma explains, “A lot of mulmul, cottons, khadi, floral prints, tweeds and handloom have been used to bring out the essence. As for the women in the film, we have tried to depict them as any other female character aiming for happiness, love and respect. There are only subtle variations of details that have helped to differentiate the characters: the style of drapes, long blouse lengths, short length loose salwars and pajamas over the traditional loose silhouettes of the kameez, puffed sleeves with short length, long sleeves with cuffs, plain cotton fabric with zari or gota embellishment, or khadi with a resham embroidered border, patterns of necklines with collars, laces and trims and styles of bindi as kumkum or chandan on the forehead.” [imgcenter]

While the pre-Partition stories have some of the refreshing, charming and glamorous vibe of Indian cinema and the Bombay Talkies, the post-Partition era needed to show a brutal saga of destruction and despair.

“The era of the Bombay Talkies has enchanting hues of deep reds, bottle green, royal blue and burgundy mixed with pastel browns and grey with slight hints of sheen to the frame, while post-Partition Lahore has been shown in ruins, with clothes tattered and the general feeling of loss and confusion in the air. So our colour palette was derived from the burnt and weathered backdrops of the refugee camps. Every single garment went through weeks of ageing, drying in the sun and washes in muddy water for texture. The costumes had to merge into the surroundings they were placed in to portray the melancholic stillness required in the frame,” adds Sharma.

Casting Nandita Das has mentioned that while working on Manto, she always envisaged Nawazuddin Siddiqui in the title role. Casting Rasika Dugal as Safiya, Manto’s wife, was a result of both Dugal’s credibility as a performer as well as her uncanny resemblance to the real Safiya. Because the film industry features in Manto, there’s also a league of supporting cast members playing the parts of Bollywood luminaries like Ashok Kumar, Nargis, K Asif, and so on.

[imgcenter]

According to Trehan, Akhtar’s decision to play the role was the biggest form of tribute from one poet to another.

Trehan says that getting all these names on board was a result of the everlasting impact of Manto and his words. “About 90-95 percent of the actors in the film belongs to the theatre or have some literature background. And every theatre actor aspires to play a character from the world of Manto at least once in their lifetime; his characters are so full of honesty and they are real-life people. Of these actors, 90 percent worked in the film for free; they all came to pay their respects to Manto. Perhaps Manto himself chose the actors who would be part of his biopic, not me. Not Nandita. He is the true casting director of the film.”

[imgcenter]

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)