“Ab-ich aatun main, pareshan nakko ho. (I’ll be there in a jiffy, don’t worry),” he assured. The man, on the other line, who was supposed to fix my air-conditioner, made me wait for three days, but everyday he repeated this phrase. Sometimes, he would drop in a shayari about parso (the day after tomorrow). Switching between Dakhani, Telugu, Hindi and English, a deft Hyderabadi knows that parso is a gaping hole of doom in Hyderabad — for that day after tomorrow may or may not come. And that’s why in Hyderabad, time isn’t real and humour is everywhere. And once you see the humour, there’s no need to worry about the time.

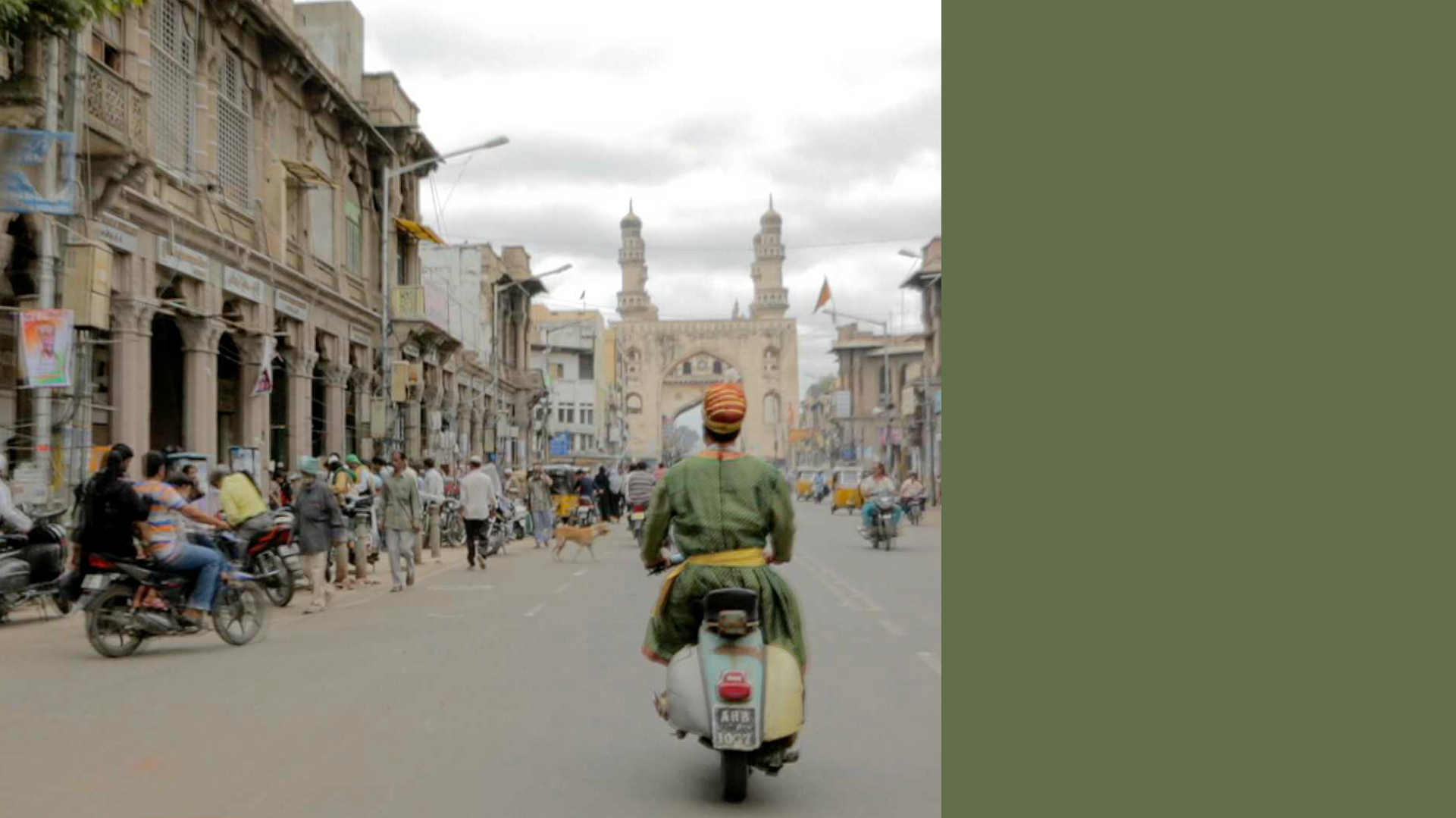

Gautam Pemmaraju, Mumbai-based filmmaker, originally from Hyderabad, set out to document Dakhani humour and satire through its decades-old culture of performance poetry. Pemmaraju began this project, Kya hai ki, Kya Nai ki: A Tongue Untied to capture the essence of mazhaiya shayari (satirical poetry) in 2011 with funding from the India Foundation for the Arts. Over the years, he realised that there was a critical question to be asked through his film: What is Dakhani? Through interviews with poets, city historians and contemporary culture, Pemmaraju paints a vivid picture of an art-form that is on the decline, but also highlights the ways in which it is being kept alive. “Many people ask, is that ‘Hyderabadi language?’ So in the popular imagination, it is the ‘Hyderabadi language’ that Mehmood is famous for through his comedy and of course through Naseeruddin Shah and others… but Dakhani is so much more than just broad caricatures,” says Pemmaraju. The language derived from ‘khadi boli’ emerged in the Deccan region and Bollywood’s interpretation of the language betrays the real essence of the language. “Dakhani is the vernacular of the Deccan which was born out of an encounter between people residing there and people who migrated there,” says Pemmaraju. Imagine a language that came into being as a result of an influx of Persians, Turks and in 1724, the Mughals and the Kayasthas coming to Hyderabad, that’s precisely what Dakhani is — the sound of two cultures merging. As Biklees I Latif writes in Forgotten, “This interaction and mingling amongst those of different regions and lands also led to the emergence of a beautiful language, Urdu, with its colourful locally spoken Hyderabadi Urdu or ‘Dakhni Boli’ which often includes an element of humour at one’s own expense.” And this “humour at one’s expense” is a part of the Hyderabadi ethos, claims Pemmaraju. “(Making fun of oneself)… was encouraged, it was also a way to kind of lighten the burdens of life,” he says.

The

lines by popular satirist Ghouse Mohiuddin Ahmed, popularly known as ‘Khamakha’ (good for nothing), encompass the defining aspect of Hyderabad’s culture. Delivered with a straight face; the lines hold, within themselves, a wisdom on how to deal with the curve balls that life throws. In Hyderabad, humour, satire lace the mundane — cheery spirits reign supreme even in the face of the biggest tragedies. Dakhani performance poetry began to be formalised in the late 1940s. And the first poets of this genre emerged during that time. Towards the 1960s, it took a little more life through the literary organisation — Zinda Dilan-e-Hyderabad — which was quite passionate in promoting humour, satire and poetry and the first mushaira was held in 1966. [imgcenter]

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)