It was a good launch for Subko, the speciality coffee roasters and bakehouse in Bandra. They announced their entry into the city’s buzzing food business with a bang, at a party featuring the who’s-who of the city’s hospitality industry. In 72 hours, they had to shut down. It was 20 March 2020 and Uddhav Thackeray announced a lockdown in Mumbai to handle the spiralling number of COVID-19 cases. It was a decision that dealt a blow to the hospitality industry — particularly to small, niche restaurants like Subko. This week, as states across India enter Unlock 1.0, a phased easing up of the lockdown, things don’t seem to have improved much for the restaurant business. Many restaurants stayed shut; those that were open saw few customers. On Firstpost:

As Indian restaurant industry eyes post-lockdown reopening, introspection aplenty on what it will take to succeed

Much has changed in this post-pandemic world. The new guidelines, hygiene and social distancing norms, changed curfew time (which doesn’t factor in dinner), rent issues, restriction on liquor sales, depleted staff, and people’s hesitance to dine out could well sound the death knell for many a standalone eating house. “These are not official figures but, I think we will see the closure of 30 to 40 percent restaurants. I know of so many people who don’t have the means to survive. This includes tiny bars, cloud kitchens and even QSR’s. Even the large chains haven’t been spared,” says Anurag Katriar, president of National Restaurant Association of India (NRAI) and CEO of deGustibus Hospitality. “The smaller spaces deal with informal ways of funding. Even if they can manage their finances, they will have a very tough time complying with new hygiene norms. In this new post-COVID world, people with lesser credibility in the minds of people will suffer in terms of business volume.” [caption id=“attachment_8477931” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

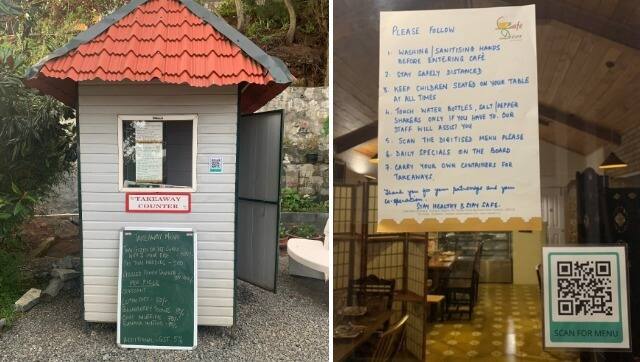

Subko had to shut down within 72 hours of its launch[/caption] New rules It’s been rough going at Subko. In April, they applied for an essential services pass (to sell coffee) but it took three weeks. With depleted staff, they started deliveries of their coffee-based products. When a resident in the building nearby died from COVID-19, they shut down again and quarantined for two weeks. Today, they are open to takeaways and delivery only. “There’s a lot of miscommunication about what is allowed or not. We haven’t gotten any updated information. We are still waiting for concrete guidelines,” says founder Rahul Reddy. There have been a few general guidelines in place for restaurants but they differ from state to state. Most aren’t allowing dining in, with the focus on deliveries and takeaways. Thermal screening of staff and every customer has become mandatory, as is hand hygiene — sanitiser and/or sink to wash hands. Masks are a must. Social distancing in restaurants means ensuring each person/table is six feet away, and not more than 50 percent of seating capacity is permitted. Disposable menus and disposable paper napkins are recommended. “From the lockdown to the partial opening up with multiple restrictions — it has been not only difficult but also for many, impractical. For most restaurants in Mumbai operating at 50 percent capacity would be unsustainable from a business perspective,” says Anish Shetty, whose family runs Durga Restaurant and Bar in Matunga, Mumbai. The family-run space opened for deliveries in May, operating with quarter of their staff. They conduct hourly sanitisation clean ups, follow contactless deliveries and their staff stays in-house. “Even though we are a bar, we are well known for our food and hence the takeaway and delivery services are doing fairly well,” he says. Katriar too cautions against the impracticality of the guidelines. For instance, how can a small hole-in-the-wall eatery or an Udupi restaurant maintain a six-feet distance between patrons? It’s why NRAI has come up with a comprehensive (yet to be released) document detailing how restaurants should tackle the realities of a post-coronavirus world. It includes protocol for every aspect of running a restaurant — from valet parking to receiving raw materials. In Coonoor, Radhika Shastry opened her eatery, Café Diem, to dine-ins this week, with many changes. There’s a ‘hygiene’ nook with a sink, and sanitiser, at the entrance. The tables have reduced by half, and are separated by partitions. Some tables are out in the balcony too, protected from monkeys by a netted curtain. The temperature of the servers is mentioned on a chalkboard. Her disposable napkins are made of banana leaf. The first day saw four customers, the second day, 10. “The interest has been very low. Here, people aren’t that keen on dining out. It is going to take a while for things to pick up,” she says. [caption id=“attachment_8477971” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

Subko had to shut down within 72 hours of its launch[/caption] New rules It’s been rough going at Subko. In April, they applied for an essential services pass (to sell coffee) but it took three weeks. With depleted staff, they started deliveries of their coffee-based products. When a resident in the building nearby died from COVID-19, they shut down again and quarantined for two weeks. Today, they are open to takeaways and delivery only. “There’s a lot of miscommunication about what is allowed or not. We haven’t gotten any updated information. We are still waiting for concrete guidelines,” says founder Rahul Reddy. There have been a few general guidelines in place for restaurants but they differ from state to state. Most aren’t allowing dining in, with the focus on deliveries and takeaways. Thermal screening of staff and every customer has become mandatory, as is hand hygiene — sanitiser and/or sink to wash hands. Masks are a must. Social distancing in restaurants means ensuring each person/table is six feet away, and not more than 50 percent of seating capacity is permitted. Disposable menus and disposable paper napkins are recommended. “From the lockdown to the partial opening up with multiple restrictions — it has been not only difficult but also for many, impractical. For most restaurants in Mumbai operating at 50 percent capacity would be unsustainable from a business perspective,” says Anish Shetty, whose family runs Durga Restaurant and Bar in Matunga, Mumbai. The family-run space opened for deliveries in May, operating with quarter of their staff. They conduct hourly sanitisation clean ups, follow contactless deliveries and their staff stays in-house. “Even though we are a bar, we are well known for our food and hence the takeaway and delivery services are doing fairly well,” he says. Katriar too cautions against the impracticality of the guidelines. For instance, how can a small hole-in-the-wall eatery or an Udupi restaurant maintain a six-feet distance between patrons? It’s why NRAI has come up with a comprehensive (yet to be released) document detailing how restaurants should tackle the realities of a post-coronavirus world. It includes protocol for every aspect of running a restaurant — from valet parking to receiving raw materials. In Coonoor, Radhika Shastry opened her eatery, Café Diem, to dine-ins this week, with many changes. There’s a ‘hygiene’ nook with a sink, and sanitiser, at the entrance. The tables have reduced by half, and are separated by partitions. Some tables are out in the balcony too, protected from monkeys by a netted curtain. The temperature of the servers is mentioned on a chalkboard. Her disposable napkins are made of banana leaf. The first day saw four customers, the second day, 10. “The interest has been very low. Here, people aren’t that keen on dining out. It is going to take a while for things to pick up,” she says. [caption id=“attachment_8477971” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

New rules in place at Café Diem[/caption]

New rules in place at Café Diem[/caption]

Hideaway Café and Bar in Vagator has seen business reduce to just 15 percent of what it was[/caption] In financial terms, it’s not just a question of rent. Restaurants have other overheads to meet. “Rent was not a concern for us, but the restaurant industry has heavy overheads which is making us bleed. These include staff costs, salaries and even something as basic as redundant stocks of beer — we did not sell anything illegally at astronomical rates,” says Shetty. Though Café Diem was open to takeaways during the lockdown, Shastry has spent the most money on diesel to run her generators. “We have a lot of power issues. When the lockdown began, we were fully stocked for summer and we have to run our freezers to ensure nothing is wasted,” she says. She had to send two of her staff members on furlough. On the other hand, there are some restaurants that haven’t opened. In Gangtok, sisters Bhavana and Manisha Sharma’s The Travel Café is still shut. “We didn’t do home deliveries earlier. It is unknown territory for us. When the café was open, we were just sustaining ourselves. It didn’t make sense opening again. Besides, people here are scared to order food,” says Bhavana. Bhat is hopeful that things will improve. He plans on opening two more outlets by the end of the year. “There will be losses but I have to find a solution. If your brand is good and you serve quality fare, you will get your customers back,” he says. The Shetty family remains positive too: “Durga survived the riots in the ‘80s, the economic crisis in 2008-09. We are expecting the government to provide some direct relief to the restaurant industry. We will get through this, together.”

Hideaway Café and Bar in Vagator has seen business reduce to just 15 percent of what it was[/caption] In financial terms, it’s not just a question of rent. Restaurants have other overheads to meet. “Rent was not a concern for us, but the restaurant industry has heavy overheads which is making us bleed. These include staff costs, salaries and even something as basic as redundant stocks of beer — we did not sell anything illegally at astronomical rates,” says Shetty. Though Café Diem was open to takeaways during the lockdown, Shastry has spent the most money on diesel to run her generators. “We have a lot of power issues. When the lockdown began, we were fully stocked for summer and we have to run our freezers to ensure nothing is wasted,” she says. She had to send two of her staff members on furlough. On the other hand, there are some restaurants that haven’t opened. In Gangtok, sisters Bhavana and Manisha Sharma’s The Travel Café is still shut. “We didn’t do home deliveries earlier. It is unknown territory for us. When the café was open, we were just sustaining ourselves. It didn’t make sense opening again. Besides, people here are scared to order food,” says Bhavana. Bhat is hopeful that things will improve. He plans on opening two more outlets by the end of the year. “There will be losses but I have to find a solution. If your brand is good and you serve quality fare, you will get your customers back,” he says. The Shetty family remains positive too: “Durga survived the riots in the ‘80s, the economic crisis in 2008-09. We are expecting the government to provide some direct relief to the restaurant industry. We will get through this, together.”

With Unlock 1.0's social distancing, sanitation guidelines, small restaurants in India face an uphill struggle in reopening

Joanna Lobo

• June 25, 2020, 10:44:01 IST

Much has changed in this post-pandemic world. The new guidelines, hygiene and social distancing norms, changed curfew time (which doesn’t factor in dinner), rent issues, restriction on liquor sales, depleted staff, and people’s hesitance to dine out could well sound the death knell for many a standalone eating house.

Advertisement

)

Shastry was able to make the required changes but for many, it isn’t as achievable. Most places are still standing because they opened for deliveries and takeaways, using minimal staff and tying up with aggregators like Swiggy, Zomato, WeFast or doing the deliveries themselves. Restaurants that didn’t do deliveries had to change their model or be creative in their outlook. The Goan restaurant, Fish Curry Rice — it has two outlets in Pune — opened for deliveries this week, serving only fish. “Fish is in short supply during this season so people are happy to order it in. Next month, Shravan will start and people will avoid meat. So, we decided to focus on fish,” says owner Sandesh Bhat. He has tied up with Swiggy and Zomato and has two dedicated personnel for deliveries. In a bid to stand out, Bhat is also serving marinated fish, and selling prepared fish by the kilo at discounted rates. Subko invested much time and money on their physical space and hadn’t planned a delivery kitchen. Reddy delivered many orders within Bandra on foot; now, they allow people to come by for pick-ups. “We have to be creative so that we can compel people to try a new brand,” says Reddy. Besides a strong social media presence, they also launched a social distancing store: a contactless menu that allows customers to order, key in delivery details, and pay. Hidden costs Though the delivery/ takeaway model seems to be the solution of the hour, the revenue earned is a fraction of what’s needed to run a business. In Delhi, Little Saigon opened for deliveries on 20 May with the three partners doing everything. Their business dropped to 20 percent. If they cannot manage rent, chef Hana Ho says they will shift to becoming only a delivery/takeaway space. Nathaniel Da Costa, partner at Hideaway Café and Bar in Vagator, has seen his business reduce to just 15 percent of what it was. “Goa doesn’t have a strong culture of ordering in. Many of our customers were freelancers who have now lost their jobs and cannot afford to order,” he says. To adapt, Hideaway is introducing affordable meals (a lunchbox), and have partnered with Swiggy. It isn’t enough. “We are running out of funds and losing money every day. I have another job but my partners do not. We won’t be able to afford rent for next year,” Da Costa says. They’ve even started looking at items within the restaurant they can sell. [caption id=“attachment_8477991” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

End of Article