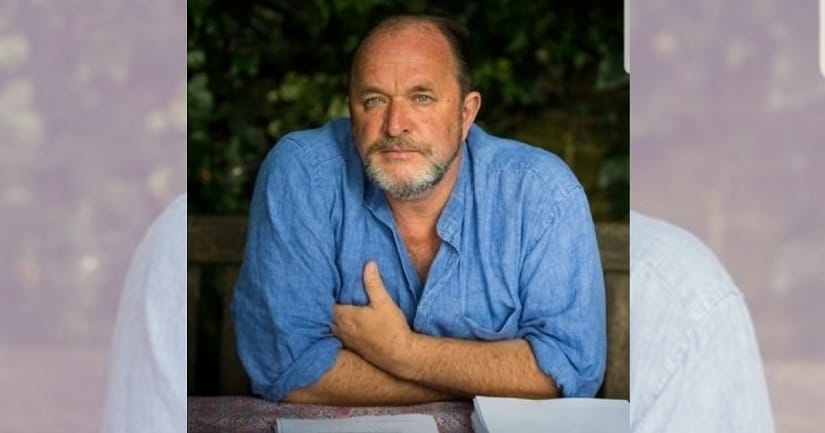

William Dalrymple walks into the business centre of the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel in South Mumbai, a little rumpled. He’s been travelling near incessantly, on a publicity tour for his new book, The Anarchy: The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an Empire. Clad in one of the blue shirts he seems to prefer, Dalrymple takes a look at the television in the room — a telecast of Queen Elizabeth II addressing the British Parliament — scoffs, and having gathered the cushions on a large couch into a comfortable, supportive heap, is ready to talk about the book. A book that incidentally, contains a fair sprinkling of Dalrymples: A Stair Dalrymple, and a James, and an Alexander. Namesakes, or family? “Oh my lord. Yes, they’re related,” Dalrymple says. “We’re a very small family, and we are exactly the kind of family from which the East India Company would recruit. It was never the top aristocrats, the earls and the lords and the dukes and so on. Three-quarters of the 16-year-olds who went out as writers with the Company never came back. But those that did come back, did so with very large fortunes. So it in particular attracted vicars’ sons from Northern Ireland or Scotsmen with larger social aspirations than their pockets or estates could provide for. Stair Dalrymple was brought up in the same house and place as me, and James was his cousin — so not a direct forebear — who married into the family of Noor Jehan, actually. Alexander Dalrymple was a cartographer who, when the Company captured Pondicherry, put together all the English and French maps and realised there must be one big landmass that he called Australia. He organised the expedition to go find it, but ended up throwing a hissy fit because the command of the expedition was given to somebody called James Cook! So yes, all the same family.” [caption id=“attachment_7502221” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  William Dalrymple. Image via Twitter/@DalrympleWill[/caption] The Anarchy is a sprawling history of the East India Company’s conquest of the Indian subcontinent, beginning with a meeting in 1599 in London, to the moment in 1859 in Allahabad, when the then Governor General Lord Canning announced that the Company’s Indian possessions were being nationalised and passing into the British Crown’s control. Several compelling characters people the pages of this history, from Company employees like Robert Clive and Warren Hastings to the Mughal emperor Shah Alam, the Bengal nawabs like Siraj-ud-Daula, Maratha leaders such as Mahaji Scindia and rulers like Tipu Sultan. Dalrymple points out that although three of his books were set against the background of the East India Company, but he’d never actually written about the East India Company before. “White Mughals is a micro study of Hyderabad from 1795 to 1805; The Last Mughal is miniature of Delhi from 1856 to 1858; Return of the King is Afghanistan, 1839-42. So I’d written these little, detailed stories, deeply researching a very short period of time in history. But I’d never actually stood back and looked at the wider picture. That’s what this is an attempt to do: to try and see the Company as an entity from 1599, and particularly the period from 1756 to 1803, when it goes apeshit and conquers India,” says Dalrymple. What drew Dalrymple to narrating the East India Company’s history was that it was “such an unlikely story”. He pulls out a picture of the Company’s headquarters in London: a fairly nondescript structure. “It’s one tiny building, five windows wide, three storeys high,” Dalrymple remarks. “And out of that small building, one English company — England at that point generating 1 percent of the world GDP, while India is generating about 37.5 percent of the GDP — one English company, somehow, improbably, using Indian capital and Indian soldiers, conquers this entire subcontinent.” Through Dalrymple’s enjoyable 400-page tome, a study in contrasts emerges: the juxtaposition of the Company’s rise in India with the Mughal empire’s collapse, the personalities of the emperor Shah Alam and Robert Clive, and quite importantly, the perception of the ‘Raj’ in India versus the reality of a corporate, profit-driven enterprise being at the helm. This last owes something to Victorians “who sort of confused the story by talking about it being a ‘British national project’,” notes Dalrymple. “They were embarrassed by the commercial, corrupt, venal plunder that preceded the Raj. They saw the Raj as this civilisational project, brought out by the kindness of Her Majesty, helping this poor, benighted nation — and the grubby reality of the loot, plunder and asset stripping by a private company of this incredibly wealthy era, was shocking. So they turned the story of Clive in India as sort of this great Imperial general. And Indian nationalists bought that story and reversed it, so that it became a story of national oppression, followed by national liberation.” Dalrymple reminds us in The Anarchy that it wasn’t actually a national story, but a commercial, corporate story. “The British no more conquered India than Facebook did. The Company was not Britain any more than Facebook is America, or Google or Exxon Mobil, or any of these giant corporations of today. And as soon as you realise it’s a corporate and commercial subject, it doesn’t absolve any of the Company’s sins, it makes them much worse. It’s so much more horrifying and shocking and unlikely. A hundred years into its history, the East India Company only had 35 full time employees and in India, never had more than 2,000 goras at any time. But they had borrowed so much money from the Marwaris and the bankers of Benaras and Pune that by 1799, they had 2,00,000 sepoys — twice as many troops as the British Army. The more you look at it, the more improbable it is, and the audacity of it — that’s what I’m trying to bring out.” [caption id=“attachment_7502231” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  The Anarchy | William Dalrymple | Bloomsbury[/caption] In documenting the Company’s history, The Anarchy delves into several turning points. The Battle of Plassey has perhaps cast an outsized shadow over several other equally important milestones in the popular imagination, but in this book, they’re all carefully chronicled — from the battle of Buxar to the treaties of Allahabad and Bassein, even the impeachment trial of Warren Hastings. And there are also the turning points that do not otherwise get their deserved attention, according to Dalrymple: the East India Company’s defeats against the Marathas in 1779, and Haider Ali and his son Tipu at Pollilur in 1780. “At that point, the Company was being held together by paperclips. One extra blow from Haider Ali could have expelled the Company from the whole of south India. But he didn’t quite have the confidence to push on. He didn’t realise how weak the Company was. And the Marathas didn’t move on Bombay, which was a big mistake,” says Dalrymple, adding with a laugh, “Or you could have had the Shiv Sena much earlier!” Some of the Company’s history, as set down in The Anarchy, reads like a modern-day cautionary tale. For instance, when Dalrymple writes of the banking crisis of 1772 that led to the East India Company having to approach the Bank of England for a handout, the parallels with the 2008 subprime crisis are hard to miss. It’s a chapter of the Company’s story that even 20-30 years ago, historians ignored because it had no modern parallels. “This is an example of how history looks very different depending on where you’re looking at it from,” Dalrymple says, adding that the 1772 crisis was important for another reason as well, because it marked the first time — 170 years after it was started — that the Company was subjected to government regulation: “In this story of the battle of the power of the corporation against the power of state, the state wins because the Company fucked up. The Company strangled the goose that laid the golden egg, allowing the government to step in. What’s interesting from a modern perspective is that with Facebook and Google and Exxon, they haven’t reached that point yet. And we don’t know what the quid pro quos are, between the huge campaign donations given by these companies to democratic governments.” Corporate lobbying was part of the East India Company’s legacy: it was the first institution to try and bribe Parliament. “It was caught with its hands on the till, offering MPs share options, in 1697 — 1697!,” Dalrymple exclaims, “in return for extending their (trade) monopoly. And they were caught, and the governor of the corporation had to go to the Tower of London with the Lord Privy Councillor.” And although the concept of a joint stock company wasn’t invented by the Company, it was certainly the first one to have such a global presence: by the 1780s, opium cultivated in Bengal and Bihar was sold in China, the profits from which got the Company the Chinese tea that could then be sold in India, Europe and even America. (It was East India Company tea that ended up in the harbour during the Boston Tea party.) It was also a precursor to modern companies threatening to move their business elsewhere if a particular regime didn’t treat them favourably. For India itself, the Company’s biggest legacy was somewhat different, says Dalrymple. “In India, you can argue that it has been a spiritual unit, a cultural unit, and a geographical expression for millennia, but there was never a single pre-Company Empire which held all the land between [Travancore] and the Himalayas — not the Mauryas, not the Guptas, not the Mughals, although several came pretty close, most of all the Tughlaqs, though no one really talks about ‘the great Tughlaqs’. But the Company is the first force that politically unified the entire Indian subcontinent, which for the first time created a pan-Indian Army. Many of the regiments in the modern Indian Army still have the names of the original Company regiments — including a Dalrymple Platoon!” Running through this history of the Company in India is the thread of the Mughal emperor Shah Alam, and his fate. Dalrymple portrays him as a tragic, wistful, noble figure — a man always in the wrong place at the wrong time. His opposite is Clive, “a man of no civilisation, no culture, no interest in India, but very effective”, a “small town thug” later turned by the Victorians into one of the heroes of British imperialism to create the Indian Empire. “Bullshit. All he did was loot and strip for a private company,” counters Dalrymple. This revisionism has led to a clouding of popular perception. As Dalrymple notes: “In both Britain and in India, for different reasons, people are still obsessed with the Raj — with a capital R — which means, in their imagination, Kipling, Curzon, the great durbar, elephants, maybe with a walk-on part for croquet matches and tea with maharajahs in Jodhpur and ladies with parasols in Merchant Ivory films. But the Raj proper was only 90 years long — 1858 to 1947. That’s not even a century, while the East India Company was around for 250 years. It’s two-and-a-half times as long as the Raj, and yet somehow we’ve forgotten it or ignored it, turning the Company into the British, which it wasn’t.” And these are very different periods, Dalrymple emphasises. “What happened during the Raj and during the Company period was very different. The Company was about asset stripping, but it was a collaboration. It did that asset stripping, in collaboration first with the Jagat Seths and then the wider Hindu banking community, and finally the people of Bengal. The Jagat Seths and others realised that although the Company spoke English, not Bengali, was meat-eating and not vegetarian, Christian and not Jain — they spoke exactly the same financial language. They were all about interest rates and repaying by such and such time. And the Jagat Seths and the Marwari community realised early on that these guys were business partners they could deal with, and the Company realised this too, and a very close relationship that predated Plassey was formed.” With The Anarchy, Dalrymple hopes to underscore the commercial — and collaborative — nature of the East India Company’s presence on the subcontinent. “You aim with a book like this to do many things,” he says. “First of all, I hope readers will see it as a as an attempt at writing an unbiased and neutral, objective view. The second thing is, where history is often written by academics rather academically, I aim to write it with as much fine prose as I am capable of and with as much depth of characterisation as a novelist might employ to breathe life into their characters. It’s so I can bring back history in the way that I’ve always thought of it — as readable and important and relevant.” And with that, he takes off to look at a wooden sepoy he’s been told is for sale at a nearby antique store.

Through William Dalrymple’s enjoyable history of the East India Company, a study in contrasts emerges: the juxtaposition of the Company’s rise in India with the Mughal empire’s collapse, the personalities of the emperor Shah Alam and Robert Clive, and quite importantly, the perception of the ‘Raj’ in India versus the reality of a corporate, profit-driven enterprise being at the helm.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)