Ghulam Mustafa Khan, mesmerising at 88 and a recent recipient of the Padma Vibhushan, sang a bhajan in Bhairavi. Nizami Brothers, of the Hazrat Nizamuddin Dargah fame, sang Amir Khusrau’s ‘Chaap Tilap’, one of the few songs that elicited requests for an encore. Rashid Khan had the audience requesting specific songs and when he got up after his allotted time ,successfully urge him to take the stage again for yet another rendition. Moinuddin Khan was also among the performers. Artists of this stature may often be a part of an event’s line up so why is it worth writing about? Well, because the event was held in a temple – the Sankat Mochan Temple in Varanasi, no less. [caption id=“attachment_4433789” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Artistes at the Sankat Mochan Music Festival. Photos courtesy Facebook/@sankatmochansangeetsamaroh[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_4433809” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Artistes at the Sankat Mochan Music Festival. Photos courtesy Facebook/@sankatmochansangeetsamaroh[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_4433809” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

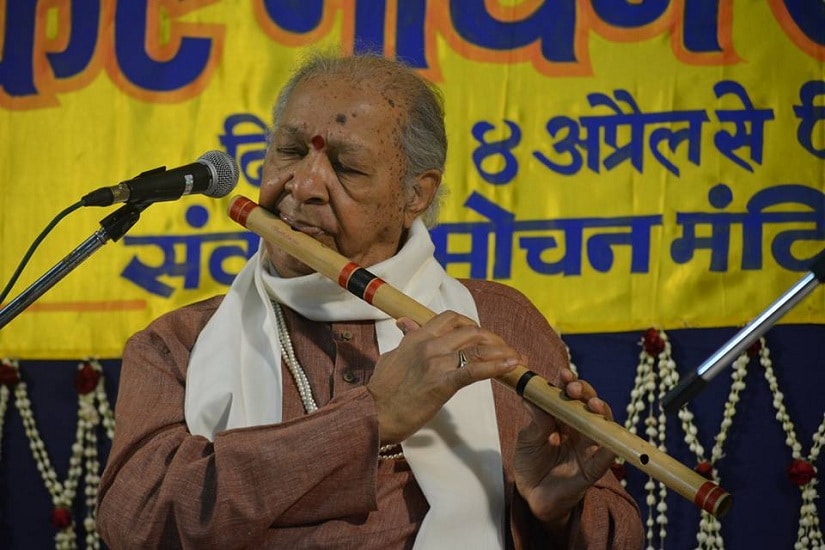

Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia at the festival[/caption] The Sankat Mochan Music Festival (aka Sankatmochan Sangeet Samaroh) is a musical event which throws the western concept of the concert out of the window. The acoustics are at best average, there is no hall — the audience fits itself into spaces within the temple precincts, devotees’ visits to temple continue (Saturday, being the day for Hanuman, witnessed quite the rush), people chat and move around. But, as I realised, this is a festival which has its heart in the right place. One where the organisers are clear about what they’re doing, and the artistes on stage are all smiles. It is ‘Indian’ at its core — fuzzy as the term may be, it’s apt in describing the ambience. Entrenched in local mores, the appreciation is not controlled claps but a very Banarasi ‘Har Har Mahadev’ (with both hands raised and vocal cords stretched); the stage is simple, basic and small, and the event has open and free access and is decidedly non-elitist. TM Krishna, during a recent visit to Varanasi, had talked of caste and hierarchy in Indian music – he has eloquently elaborated on the topic in his columns and books – I am curious about what he would have made of this festival. The festival, a two-day event during the 1960s, has by its 96th edition in 2018 become a six-day (rather, night) affair. Beginning at 7.30 pm, the performances last well into the morning hours. A photo exhibition is also organised at the venue. The absence of mobile phones (banned in the temple since the 2006 bomb blasts) helps, as does the presence of the prasad shop. The sweets here are well-known even in this town of sweets, lal peda and besan laddu being the stars. The ‘uncle’ at the water-point hums and sings as he pours water into the cupped palms of thirsty music lovers and devotees. Conscious simplicity also means less generation of plastic trash. Nandini Majumdar in ‘Why the Sankat Mochan Music Festival in Banaras is so special’ writes: “A festival like Sankat Mochan – in which artists perform for free, citing their devotion to Hanuman as a reason for doing so, in which ordinary people turn up in the hundreds all night long to listen to ‘classical’ music, and in which the overall ethos is one of the intimate, the humble and the humane – is an example of living, practiced, everyday bhakti that is quite amazing to witness, and is a striking reminder of how it continues to infuse life for many in India’s smaller places with meaning.” [caption id=“attachment_4433791” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia at the festival[/caption] The Sankat Mochan Music Festival (aka Sankatmochan Sangeet Samaroh) is a musical event which throws the western concept of the concert out of the window. The acoustics are at best average, there is no hall — the audience fits itself into spaces within the temple precincts, devotees’ visits to temple continue (Saturday, being the day for Hanuman, witnessed quite the rush), people chat and move around. But, as I realised, this is a festival which has its heart in the right place. One where the organisers are clear about what they’re doing, and the artistes on stage are all smiles. It is ‘Indian’ at its core — fuzzy as the term may be, it’s apt in describing the ambience. Entrenched in local mores, the appreciation is not controlled claps but a very Banarasi ‘Har Har Mahadev’ (with both hands raised and vocal cords stretched); the stage is simple, basic and small, and the event has open and free access and is decidedly non-elitist. TM Krishna, during a recent visit to Varanasi, had talked of caste and hierarchy in Indian music – he has eloquently elaborated on the topic in his columns and books – I am curious about what he would have made of this festival. The festival, a two-day event during the 1960s, has by its 96th edition in 2018 become a six-day (rather, night) affair. Beginning at 7.30 pm, the performances last well into the morning hours. A photo exhibition is also organised at the venue. The absence of mobile phones (banned in the temple since the 2006 bomb blasts) helps, as does the presence of the prasad shop. The sweets here are well-known even in this town of sweets, lal peda and besan laddu being the stars. The ‘uncle’ at the water-point hums and sings as he pours water into the cupped palms of thirsty music lovers and devotees. Conscious simplicity also means less generation of plastic trash. Nandini Majumdar in ‘Why the Sankat Mochan Music Festival in Banaras is so special’ writes: “A festival like Sankat Mochan – in which artists perform for free, citing their devotion to Hanuman as a reason for doing so, in which ordinary people turn up in the hundreds all night long to listen to ‘classical’ music, and in which the overall ethos is one of the intimate, the humble and the humane – is an example of living, practiced, everyday bhakti that is quite amazing to witness, and is a striking reminder of how it continues to infuse life for many in India’s smaller places with meaning.” [caption id=“attachment_4433791” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

The audience at the Sankatmochan Sangeet Samaroh. Images courtesy the writer[/caption]

The audience at the Sankatmochan Sangeet Samaroh. Images courtesy the writer[/caption]

Varanasi's Sankat Mochan Sangeet Samaroh celebrates the city, and the Indian classical music tradition

Nimesh Ved

• April 18, 2018, 20:23:01 IST

‘Banarasi’ is the term which best describes the Sankat Mochan Music Festival — like the town, it is difficult to comprehend, thrives on chaos and defies logic.

Advertisement

)

It is only befitting that an event which is emblematic of diversity is helmed by a person with wide range of interests: Vishwambhar Nath Mishra, the mahant of the iconic temple, which is believed to have established by Tulsidas (who wrote Ramcharitmanas) during the 1500s, is a professor of Microelectronics at the Indian Institute of Technology, Banaras Hindu University. He is also the president of the Sankat Mochan Foundation which is at the forefront of a movement for cleaning the Ganga. Coming back to the artists, the mind-blowing line up of the festival this year also included Niladri Kumar, Vijay Ghate, Sonal Mansingh, Dr L Subramaniam, Birju Maharaj, Malini Awasthi and Hariprasad Chaurasia besides others. It is not just the artists but also the audience who maketh a festival! The local newspapers mentioned Radheshyam Tiwari of Patna who celebrated a golden jubilee of attending the event during this year’s edition. A friend, when asked whether or not he would attend that evening, replied: ‘If Birju Maharaj can dance at 80, I can surely attend at 65’. He came on most days with a steady companion – his pillow. Many in the audience happily lay (provided they found the space) in the open courtyard and enjoyed the music and mahaul on the large screen. The festival did broadcast performances live on Facebook! Local publications also highlighted a well-known out-station school visiting – the local schools however were conspicuous by their absence. Where else could students experience music of this calibre at such close quarters, I wondered. ‘Banarasi’ is the term which best describes the festival — like the town, it is difficult to comprehend, thrives on chaos and defies logic. And despite all this, much like town, the festival has an indefinable quality which makes it work; it touches people and how! The writer loves long walks and silences. He blogs

here

and can be reached at nimesh.explore@gmail.com

End of Article