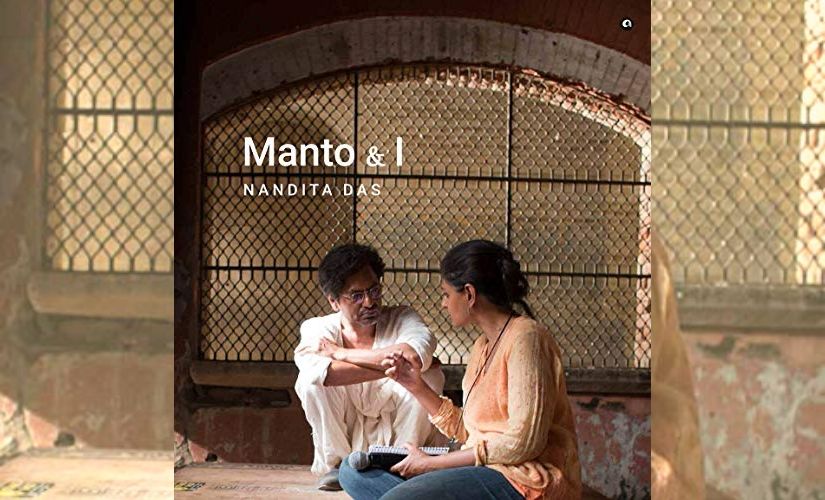

Nandita Das’s debut book Manto & I is a comprehensive exposition of her journey with the 20th century Urdu writer, Saadat Hasan Manto, through celluloid and beyond — a tale spanning six years of uncovering the man, bit by bit, every bone and sinew that made — and more often than not — unmade him. Only a year since her film Manto (2018) took her across the world to a myriad festivals and meets, Das is on the road yet again, with Saadat Hasan continuing to keep her faithful company. “What is it about Manto that doesn’t leave you, or you don’t leave him?” writer and lyricist Niranjan Iyengar asked the freshly-minted author at the Tata Steel Kolkata Literary Meet. A couple of hours before that, Das was sitting in a sunny poolside-cafe at The Taj, talking to us over lunch. “This is my breakfast, lunch, and dinner, as I am flying out right after my session,” she informed me, having landed from Jaipur (after a session at the Zee Jaipur Literature Festival) barely hours before our meeting. “Don’t you wish there were a term for such an all-in-one meal, like ‘brunch’?” I asked. With a nod and a laugh, she insisted we join her for the meal, warning us that she would only stop eating when the interview was over. “You might hear me go ‘chomp chomp’ in your recording,” she joked, as I set my phone down next to her plate, and dove right in. [caption id=“attachment_7964331” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Manto & I, by Nandita Das[/caption] In Manto & I, you mention, right at the outset, that after the gruelling 44-day-long shoot, you weren’t quite sure if the film you’d imagined would emerge. But on seeing the stills taken on set, you finally felt like there was a film there. Now that it’s been around a year-and-a-half since Manto released, do you think people have perceived the film you’d envisaged? I think so…largely. The feedback was very, very overwhelming for me. What really worked for me was that I made the film respond to what is happening today, and people were able to see the parallels in the film. Even though it was about something that was happening 70 years ago, people could see that it was coming from the concerns and the angst of today. For me, that was really important — how people could immediately see the parallels, and not perceive it as just a biopic. People could see the troubles of the times, Manto’s own struggles, issues of identity and censorship. At the end of the day, the audience’s response tells me more about them, than it does about the film. Film toh jo hai, so hai — good, bad…I know more about all the things that need to be fixed. But when people share what they like, didn’t like, what they felt, they are, in some ways, telling me more about themselves. To see how different people have reacted to the film across continents has been interesting. And thanks to Netflix, people across the world are watching the film. So, whether I take it to a campus in the US, or I show it in a small college in India, it really proves the power of art and cinema. It transcends boundaries and cultures, because at the core, human experiences are universal. [caption id=“attachment_7964341” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Nandita Das. All photos by Tanumay Naskar for Firstpost, except where indicated otherwise[/caption] In the book, quite interestingly, you mention that Manto reminds you of your father. Did this epiphany, if I may call it that, contribute to your process of understanding the writer any better? I don’t know if it was an epiphany, but I think that since I could immediately see the parallels between Manto and my father [painter Jatin Das], I felt emotionally more equipped to do the film, because otherwise, everything has to be understood from the written word. His family did tell me a lot about him, but most people who knew him are not even there anymore, as he passed away in 1955 at the young age of 42. So, to understand what he must’ve been as a human being beyond the written word that was available, became possible only because I realised my father was so ‘Mantoesque’ in so many ways. There were so many similarities between them — whether it’s about being a misfit, being too blunt, or telling the truth in ways that can almost be perceived as being rude at times, or having no relationship with money and being totally driven by one’s passion for work, being very generous and keeping the house doors open, — those were the same stories I would hear about Manto. He would constantly feed people even when they had no money, and his wife would complain. Manto would write in the middle of chaos when his children would be playing — my father would work like that…I work like that! So, in many ways, I felt that Manto was familiar to me. He wasn’t a quirky someone out there — I would’ve still made a film on him, because you can always imagine a character. So in some ways, knowing my father helped me understand Manto. And being with Manto for so long also helped me understand my father better…there is a connection.

Yes, these are very polarising times. Everything has become a binary, a sound bite or 140 characters — there’s really no space for nuances. So, even if I say that yes, I am fine working with Paresh Rawal, I can be completely misunderstood, and be asked as to how can you say that the art and the artist are inseparable, when you’re fine working with him? But what I am saying is that I would like to engage with that disagreement, and I have engaged with him on multiple occasions. I am not brushing it under the carpet. However, I don’t want to be screaming and shouting — I have done that too in my younger days, and have gone on television debates and screamed at marches and have held posters.

I am in a different place in my life right now, and I feel like the only people I want to engage with now are the fence-sitters. For that, I need to listen in order to be able to understand why they feel a certain way. Because otherwise, we are only talking in our echo chambers, and posturing to each other as to how liberal we are. What’s the point in that?

I don’t want people to think they are coming to attend a lecture. We seldom celebrate our writers and artists. There’s really no film made on them. In fact, a journalist told me that there’s not a single Hindi film on a writer, besides Manto. And I was wondering, how can that be? And then I realised that there is one more film on a writer, and that is the one that Manto wrote on Mirza Ghalib. How sad is it that we don’t celebrate these people, who are the mirrors of our society.

I feel that when people come without guards and become vulnerable to the story, that is when they start absorbing what the film is trying to say. What cinema does is something very subtle — we can’t calculate or quantify a film’s impact. It seeps into our subconscious so subliminally that we don’t even know which books or films exactly have impacted us. But these are the things that actually change us. So, my core has been the same throughout, but I know I am not the same person I was 20 years ago. You have always been very vocal about your politics, like you mentioned earlier. However, several artists and actors across India, and not just in Bollywood, have refused to take a stance on political matters, and have identified themselves as ‘apolitical’… …Yeah, I don’t understand what that means. There are journalists who say that too. They think calling themselves ‘apolitical’ makes them objective. Yes. So do you think writers and artists have the luxury of being ‘apolitical’, without running the risk of being termed irrelevant today?

See, saying that I am ‘apolitical’, or that these issues don’t concern me, or I am not concerned about them, also shows your politics. It means you don’t care.

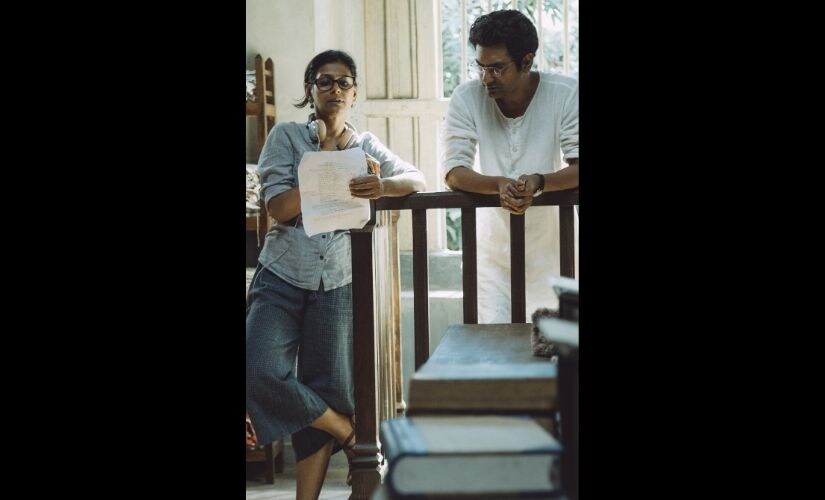

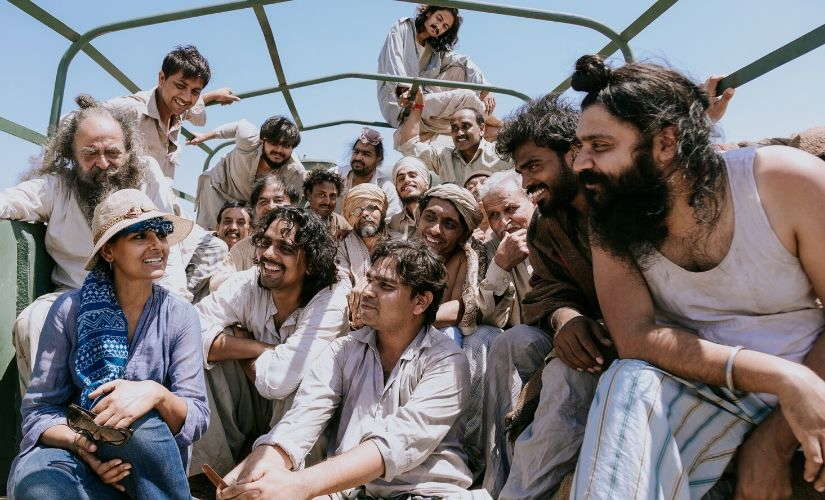

Do you think such statements reflect a kind of privilege, where said public figures can afford to not engage with issues that affect the common man? But in some sense we can all be that. Anybody who’s not having to toil for their daily bread is privileged — you and me, and some others. In some sense, we are all privileged, not just because we’ve had access to education, clothes, and a roof over our heads, but also because we are doing what we love to do. That in itself is such a privilege. Most people don’t have an option but to do what they have to do. So, I don’t think it’s so much about privilege, as it’s about a convenient way to distance yourself from what’s happening around you. We don’t live in isolation or on an island. If you want to be peaceful, even for selfish reasons, you’ve got to have a peaceful world. It’s not a ‘choice’, to be conscious of the environment, or the fact that the world is becoming more violent and bigoted. That should be your default response, your instinct. And that is what I am appealing to everyone, that it’s about being a human, a citizen. Please, show your humanity. Would you not want to be dealt with equally irrespective of your caste, the colour of your skin, your religion, sexual preference, or gender? It’s insane, the number of ways in which we are creating the ‘other’. This way, every person can be the ‘other’ for someone, right? [caption id=“attachment_7964511” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Nandita Das with Nawazuddin Siddiqui on the sets of Manto. Photo courtesy Aditya Varma[/caption] However, who are we to decide if someone is relevant or not? It makes us too righteous if we say that, “oh, you and I are relevant, because we’ve taken a certain stand”. These are celebrities, but there are also very regular people who are struggling with their daily lives — they are not putting out a political stand either. I think that if you believe in freedom, you must believe in other people’s freedom as well. You may disagree with them, and say that I can never see myself being that, but somewhere down the line, you should also give them the freedom to be the way they are. I don’t want to waste my time flogging others; I want to spend my time working towards another narrative that I believe in, and let people decide which narrative they want to subscribe to. This is true of films as well, right? There are so many hardcore commercial films, and people ask me as to what I think of the masala films that are regressive, and have item numbers, objectifying and stereotyping women. We are not going to be able to change that. And even people who watch it sometimes say that what do we do, those are the kind of films that come our way. It’s a vicious cycle, and only you can break it. Like the entire debate centred around the film Kabir Singh (2019), and the message it tried to convey… Right. I haven’t seen it, but I’ve heard it’s very, very misogynistic. But if it’s doing well, for me that is of greater concern, and not why somebody made it. That is that person’s perspective. However, if so many people are watching it, and if the channel that is spewing so much hatred is garnering the highest TRP, then the finger has to be pointing more towards us than them. For the corporates, it’s a business, and if it’s working, then why not go ahead with it. Finally, what are the projects you’re currently working on? I am developing a couple of projects — there’s a feature film I am writing, a short film that I am working on, a documentary idea that I am toying with. Nothing is a 100 per cent complete yet. I am getting a lot of acting opportunities, and I might work on some of them. [caption id=“attachment_7964521” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Nandita Das on the sets of Manto. Photo courtesy Aditya Varma[/caption] You know, it’s only one life, and I don’t want to be busy just for the sake of it, I’ve never done that. Also, with the digital boom, there was suddenly so much work just after I finished Manto, with people asking me to direct this, and show-run that, and direct two episodes of a show. There was so much money coming my way that all my friends thought I was being completely foolish, considering how nine-tenths of my work is pro bono. I don’t associate work with money as such — work doesn’t necessarily mean what you get paid for. For me, film is not really a business. I want to earn also, I am not saying I don’t need money. But if you keep your needs in check, you don’t need too much. And when are we seeing you on screen next? There’s this series I might do in March, I am not sure. Talks are still on. But directing is what I think I really enjoy. I am developing a few projects, and some producers are interested in funding them…I am doing them at my pace. I work from home, and my dining table doubles up as my work station. Now, for the first time, I feel like I want to get a separate space where I can work, and then come back. Otherwise, I am a distracted mother and a distracted working person. And I think that is the first step in the direction of instilling some method into my madness.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)