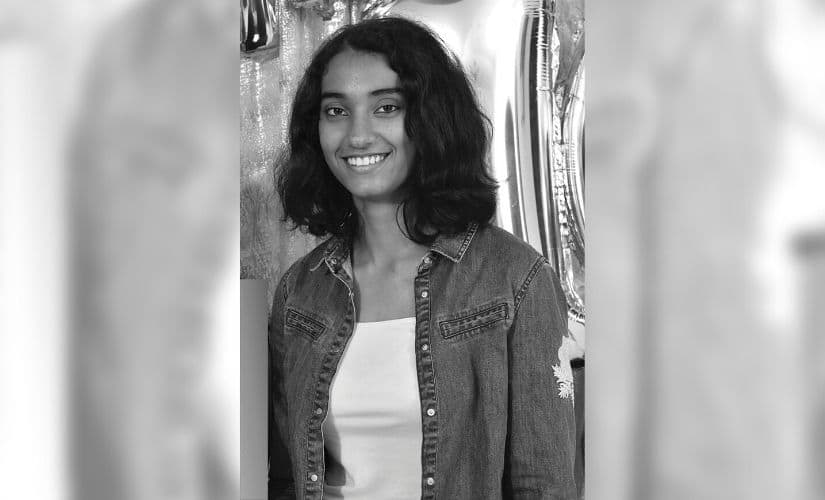

Harper Collins has just published a collection of stories written by a 16-year-old author. Titled This Is How It Took Place, the book is a collection of interconnected short stories, by author Rudrakshi Bhattacharjee, who attended school in Bengaluru. She received both encouragement and recognition at an early age, besides getting mentorship from a senior writer courtesy of The Adroit Journal, a prestigious platform focusing on younger authors. She also got a chance to attend Stanford University’s residential course in creative writing at the age of 14. Tragically, Bhattacharjee left us at the age of 16, passing away in 2017. She would have been 18 when her first book came out. Though the book has been endorsed by Jeet Thayyil, who calls the writer ‘Prodigious, gifted, precocious,’ many of the stories remain raw and uneven. And yet, the three stories that are truly complete — the title story, ‘A Vacancy’, and ‘La Mer’ — are enough to justify Thayyil’s blurb. As someone who dreamed of being a writer since he was nine, I, too, received encouragement and minor praise for my writing, but at no point was I good enough to conceive a plot like the one in ‘This is How It Took Place’. In it, teenager Bhattacharjee imagines a 27-year-old woman in love with two men, one her age, and another an older, underemployed poet. She deftly switches from one strand of the plot to another, reaching a conclusion full of psychological insight. [caption id=“attachment_7679791” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Late Rudrakshi Bhattacharjee. Image courtesy: https://harpercollins.co.in/[/caption] One can see in the story the instincts of a storyteller: a natural grasp on point of view, an ability to create fully realised characters using short strokes, and, most of all, the engine of a plot. When writer Akhil Sharma spoke to my Master of Fine Arts class, he said the one thing most students seemed to lack was a grasp of what gets a plot going. What makes you feel like you cannot put the book down?; what makes you curious to find out what happens next? The basics of these seem so much in Bhattacharjee’s control that on the basis of this one story alone, one can project a career as an author. Bhattacharjee also has an unerring eye for moments with dramatic tension. One short story again lacks many of the basics of storytelling, but contains a living, beating heart: the experience of the girl who finds herself not popular enough, and trailing after her popular friends who are studiously ignoring her. The feelings that this storm-in-a-school-teacup induce are violent and catastrophic, even though the canvas is small. The small creature who inhabits that small world — the adolescent — is as disturbed by the dislocation of her social position as an adult would be at losing their job, or a city would when faced with a natural disaster. These feelings are telegraphed through potent images. Bhattacharjee writes: “But then I trip, and my friends are moving away too fast for me to reach them and I am so far behind them that I only see the ends of their dusty sports shoes and their legs which look like peach ladles. They are bounding away and crushing the spines of fallen leaves, breaking the bones of venturing scorpions, leaping into the oncoming dusk.” Similarly, she picks the moment of moving into a new housing colony and discovering over there, amid perfectly nice people, three nosy women, who remind me of the dreaded gossipy aunties, adroitly policing the reputations of young girls even in big Indian cities. The parts of the book that are not praiseworthy are also telling in their own way. In Bhattacharjee’s work, like in my own as a younger writer, — and in that of many other younger Indians I have encountered writing in English — the character names are almost always western. So much so that one-third of the stories have their lead characters named Romeo and Juliet. What is it about us English-educated people that disconnects us from our own people? Why do our stories not use Indian names and settings? Even ‘This is How It Took Place’ is set in New York. Similarly, the other stories lack something my professors drilled into me: clarity of setting. We never quite know where we are, and there are very few passages that set the scene. This, once again, feels like postcolonial dislocation. I remember being taught not to use Indian languages — what Purushottam Agarwal calls deshbhashas, as an alternative to the less desirable connotations of the term ‘vernacular’. I remember knowing the names of more British trees than Indian ones, all because so much of my reading had been of western writers. Interconnected short stories haunted by dysfunction The form of the book mimics a collection of interconnected short stories — a form I particularly cherish and have attempted in the past. A great example of interconnected stories is Junot Diaz’s Drown (who has been called out as a harasser). Like Drown, Rudrakshi Bhattacharjee’s collection features many variations of similar themes. We have the rebellious adolescent girl, typically the protagonist, though in one affecting story, ‘Who Else Will Love the Damned’, she is the idolised elder sister of the narrator. The mothers are neglectful and uncaring, preferring their book clubs or sneaking out at night after the daughter is asleep to do what is left only as implication; where a mother is caring, it is in the most grotesque of ways, with one story playing on the ‘Manchausen’s-by-proxy’ trope. This phenomenon has seen a renaissance with two major television shows based on the syndrome — one, a true crime story called The Act, and the other a fictional take, Sharp Objects, based on the novel by popular literature superstar Gillian Flynn. Meanwhile, the fathers are all absent — either inveterate travellers, or adulterers, or deserters who have left deeply selfish mothers alone with their daughters. Like Drown, there is one story where a living father makes an appearance, waltzing in after three years. Indian fathers are shown as so disconnected from parenting that they think their 14-year-old is still studying the Pythagoras theorem. Underlying many of her dramatic plot points, Bhattacharjee reveals truths for any with the stomach to decipher them. But the writer does not stop there in her indictment of masculinity — apart from their absence, these men are also often unemployed, or engaged in meaningless jobs. The upshot is that all these fathers are ignoring their children while doing little of consequence. The ‘anger against bullshit jobs taking their parent away while the mother raises the child’ is palpable. [caption id=“attachment_7679801” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Cover of This is How It Took Place, by Rudrakshi Bhattacharjee.[/caption] Meanwhile, the rebellious teenage daughter is also severely distressed emotionally, battling severe guilt, or attempting suicide, or having within her a desire to lash out and hurt people close to her. Bhattacharjee captures, with great fidelity and insight, the experience of mental illness in adolescence. In a well-wrought story, ‘La Mer’, she describes anxiety: “By the next day, the daughter has chewed and bitten her fingers to the point where the side of each is bleeding. In school, the daughter sucks her fingers violently, almost devouring the dried metallic blood on the sides, a beast baring her fangs, licking her arms and trying to stop her hand from aching. It is no longer just an irritation: it has been transformed into a threat, a slice of agony, a retelling of torment. She fantasizes that she’ll need anesthesia, and she’ll have about the twenty minutes of pure, uninterrupted rest, when her brain will no longer click and her insides will no longer churn, and all she’ll feel is the humdrum swaying of her own shallow breathing. She will become a quiet, downy body. She will not be ruffled; she will not be waylaid. She’ll be like a piece of thin, cool marble, a slate of stone, steadfast and rooted, she will not drown.” The Kids Are Not Alright It is this last story that is the most telling. Of late, I have been thinking through what it means for people to tell their own stories, exploring their own experiences, instead of it being explained to them by so-called ’experts’. Recent years have seen an explosion of Young Adult novels, but apart from rare exceptions like Christopher Paolini’s Eragon, the books are mostly written by adults, with genre conventions that they feel will suit the sensibilities of younger readers. In Rudrakshi Bhattacharjee’s work, we get the rare opportunity to see what this generation has to say for itself. In this, I compare her to an absolute phenom in the US — Billie Eilish, who, unlike earlier teen sensations, seems to own her songwriting and her talent. Both Bhattacharjee and Eilish take a sledgehammer to any genteel conception of adolescence. Rudrakshi exposes the dysfunction in families, with deranged adults anxious to show the neighbours up while simultaneously furiously repressing their own flaws. Parents repeatedly react to tragedy with denial, failing to address their emotions and those of their children. Though the names are western, the themes are stridently Indian. Log kya kahenge? is the dominant concern, with what the children are feeling coming a distant second, to the point that this incomprehension and neglect turns the children suicidal. Both Eilish and Bhattacharjee show that they are raw nerves that not only register the world, but also register it keenly and powerfully. Eilish sings about self-loathing and death and drugs; her popularity seems to speak to an America raised on a steady diet of school shootings. In this, Eilish is the true heir to the alternative rock movement that smashed the polished pop of Michael Jackson with tracks like Pearl Jam’s J’eremy’ and Nirvana’s masterpiece, Nevermind. Much like the baby grubbing after a dollar bill on the Nevermind cover, Rudrakshi’s adults are often chasing some illusory idea of success that is always out of reach. Lastly, as adolescent girls, both Eilish and Bhattacharjee lay bare the way their bodies are policed. One Rudrakshi story turns on a brother taking photographs of his sister when she is unaware — the word used is ‘exposed’, suggesting the photos have violated her in a way left unsaid. He then publishes them online, where they go viral as ‘art’. The mother, originally horrified by her son’s violation, is thrilled when she realises the photographs are being praised by critics. Meanwhile, the young girl’s horror at being violated is swept away with a blithe ‘Stop being dramatic, they’re just pictures and you look lovely’. Unlike Britney Spears or Miley Cyrus, who respond to the horrible regime of insecurity instituted by a world obsessed with bodies by transforming their own, Eilish chooses to wear baggy clothes to refuse to participate in the game at all. She explains herself (ironically in a Calvin Klein ad), saying: “I never want the world to know everything about me. I mean, that’s why I wear big baggy clothes. Nobody can have an opinion ‘cause they haven’t seen what’s underneath. Nobody can be like oh, she’s something, she’s not something. She got a flat ass, she got a fat ass. No one can say any of that, ‘cause they don’t know.” Eilish’s fashion is as much of a sledgehammer as her music, a giant ‘f*ck you’ to toxic standards. Bhattacharjee’s response is different, caught in the twilight zone of deeply resenting these standards, while also being naked about the toll they take on her characters. In one moment that will be familiar to many girls, a daughter describes what her mother says to her: “At other times, what she said was more repugnant simply because it was true. And because my mother had an uncanny ability to sense where the blade would draw the most blood when she struck it. ‘Another plate, really, this is the age where you start to gain, don’t be naïve, you know how fast you put on.’ Her slippery tongue sliding in like a snake’s.” Of course, today I find it hard to really relate to Nirvana (though Eilish is very compelling). Perhaps what I have called the ‘basics of storytelling’ are just the scaffolding that ‘serious’ adults require; perhaps adolescents will read Rudrakshi Bhattacharjee’s prose very differently, and come off impressed, inspired, and with a feeling of being understood. As Jack Halberstam wrote, ‘when we enter a classroom and refuse to call it to order, we are allowing study to continue, dissonant study perhaps, disorganised study, but study that precedes our call and will continue after we have left the room’. These themes, ideas and emotions will continue to circulate whether they get the stamp of adult approval or not. As a result, perhaps what we should advocate is a different approach: where adults listen to adolescents and take them seriously. Even if we want to deny the clarity with which a Greta Thunberg sees the disasters we are heading towards, we can at least consider them as authorities on themselves, fully capable of expressing what they really need. We can put down our adult frailties and egos, and truly listen.

Rudrakshi Bhattacharjee’s This is How It Took Place is a collection of short stories written by the 16-year-old author, who passed away in 2017. Though the book has been endorsed by Jeet Thayyil, who calls the writer ‘Prodigious, gifted, precocious,’ many of the stories remain raw and uneven. And yet, the three stories that are truly complete — the title story, ‘A Vacancy’, and ‘La Mer’ — are enough to justify Thayyil’s blurb.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)