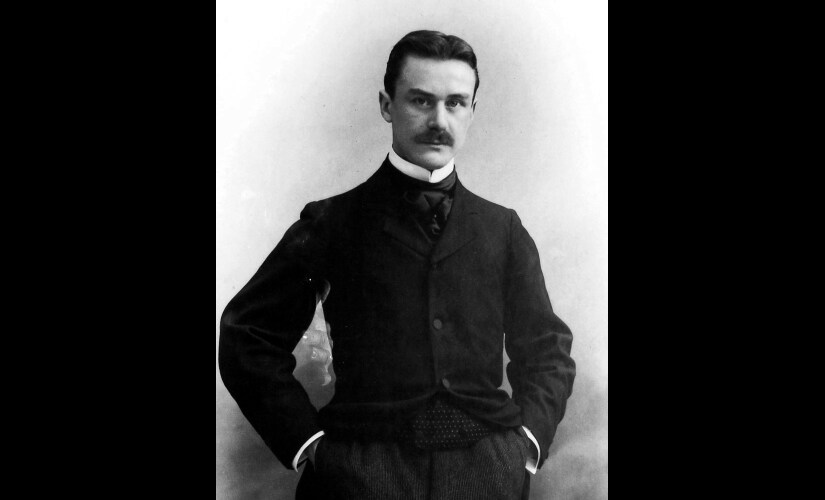

There are stories, read long ago, which live on in the backrooms of the mind, becoming perennial furnishings of our mental lives, refusing to fade even after the passage of decades. In this column , every month, I shall share one such story with you, a story which has nourished my inner life and which deserves to be unpacked and aired in the hope that it will bring you the same pleasure and insight that it brought me. *** Thomas Mann’s story Little Lizzy leaves an inchoate pang in the reader, the proverbial lump in the throat. For it deals with an uncategorised specie of victimhood, one of the denied, the deprived and socially damned, though never with a capital ‘D’ to dignify the situation. By convention classed as unforgivably idiotic and to be held up to public ridicule, this specimen happens to be that ungainly, pathetic ignoramus, the cuckold. For that is what Jacoby, the doting husband turns into – Little Lizzy. Grotesque, contemptible, the laughing stock, whose moment of truth is his moment of death. On the face of it, the central character of the story is Amra, an anagram for Anna Margaret Rosa Amalie, an exotic beauty, sensuous and mysterious, of ‘slow, voluptuous, indolent presence’ but also gifted with what the author describes as ‘a kind of luxurious cunning’. How malevolent this luxurious cunning can prove is what the story demonstrates. The victim is her grossly unpresentable husband, the lawyer Jacoby who is forty, fond and foolish. [caption id=“attachment_7942661” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Thomas Mann. Image via WikimediaCommons[/caption] Jacoby is as repulsive as his wife is attractive. And the author makes his tragic grossness come alive. ‘His legs, in their columnar clumsiness and the slate-grey trousers he always wore, reminded one of an elephant’s. His round, fat-upholstered back was that of a bear; and over the vast round of his belly, his funny little grey jacket was held by a single button… strained… tight.’ His head holds ‘narrow, watery eyes, a squabby nose and a wee mouth between cheeks drooping with fullness.’ They are an ill-assorted couple but they are well-to-do, live in a well-appointed home and entertain enthusiastically. To be precise, she entertains and he foots the bill and complies with every whim of hers, for he loves her to distraction. This dumb worship manifests in abject appeals to her to stay faithful to him despite his personal unworthiness and her own surpassing excellence. She responds with indulgence, as one would to a slavering dog. The whole town is aware that she has a lover, only her deluded husband believes in her fidelity. The lover is all that the husband isn’t – young, debonair, a dashing and talented musician and composer, not blest with true genius but clever and innovative. The affair is an enduring one and it achieves its finest stroke of artistic cruelty when Amra persuades her willing husband to throw a springtime party to celebrate the new beer produced in the town’s brewery cum outdoor restaurant. The entertainment provided, aside from the food and drinks and dancing, is a series of performances put up by the guests – singing, mimicry and skits. But the crowning event of the evening is something no-one is prepared for. The mild, obliging husband, who seems to be ever apologetic about his mere existence, sits on tenterhooks all through the evening’s roistering. He has been talked into agreeing to present a comic song-and-dance number called ‘Little Lizzy’. It is a composition written by the lover and it is played on the piano by four hands, the lover and Amra sitting side by side at the keyboard. The poor performer appears to be in acute nervous agony. He makes his appearance, dressed in the most absurd costume, a baby frock with puffed sleeves, cut low front and back to exhibit his puffy, corpulent form to its maximum disadvantage. He is miserable but he jigs stiffly before the audience, using his very limited repertoire of actions that only serve to highlight his ponderous bulk and provoke everyone to irresistible laughter. But no one laughs. The spectacle of a fat man rigged out in the most ridiculous costume, dancing in craven obedience to a wifely command stuns the onlookers. The cruelty of it as well as the pathetic shabbiness of his situation is shocking. The tune is brisk and the song is ‘Little Lizzy’. The pianists at the keyboard outdo themselves, evidently in a high state of glee. Suddenly the meek dancer realises. Some intuition pierces the illusion of doting trust with which the poor man has all along protected himself. He takes in the entire situation, the two mocking pianists, the look in the faces of the subdued audience and his own clownish attire. And he understands whatever is to be understood. It fells him like a blow. He collapses in a dead swoon, dressed in his awful costume, and dies of shock. Not like a hero but only like the figure of farce he had been turned into at the behest of a cruel woman he loved with an anguished, adoring faith. The pain and the shame make it a deeply disturbing story and there is a surge of classic pity and terror at the terrible ignominy of a poor man who is not cut out to be one of life’s romantic heroes or even one of its epic anti-heroes, but is fated to be just a clumsy, clodhopping oaf who loved and lost all. A very haunting story and extraordinarily moving. Look it up.

Thomas Mann’s Little Lizzy deals with an uncategorised specie of victimhood, one of the denied, the deprived and socially damned, though never with a capital ‘D’ to dignify the situation.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)