There are stories, read long ago, which live on in the backrooms of the mind, becoming perennial furnishings of our mental lives, refusing to fade even after the passage of decades.

In this column

, every second Saturday of the month, I shall share one such story with you, a story which has nourished my inner life and which deserves to be unpacked and aired in the hope that it will bring you the same pleasure and insight that it brought me. *** The Death Of Ivan Ilyich isn’t just a story. It’s a spiritual re-orientation retreat. I read it every few years and each time I find new insights to mentor me, and also fresh corrections to my socially programmed life patterns. This story has been a textbook of life to many people, which is significant considering that it’s about death. One man’s intense interface with death throws into focus his late realisations of his mismanagement of life. Heart-stoppingly tracing the mindless trajectory of our superficially aspiring lives, our misplaced emphases on what constitutes success and our various flawed definitions of a life well lived. All construed in a context in which although we know that nothing endures, there is still the piercing need to believe in the ultimate worth of something. Ivan Ilyich is, at the close of his career – and his life – at age 45, a member of the Judicial Council of a Russian province. He is the achieving son of an official who, ‘in various ministries and departments in St Petersburg, made for himself the sort of career which brings men at last to a post from which, even though it is clear they are incapable of doing anything of true importance, it is impossible to dismiss them because of their long term of service and high rank.’ In other words, a cog in the bureaucratic machinery of Tsarist Russia in the mid-nineteenth century, one of those who hold ‘fictitious offices and receive by no means fictitious salaries.’ Ivan Ilyich has a career similar to his father’s, beginning as Special Commissions for the Governor of a province. A conveniently fuzzy designation from which he commences his climb up the bureaucratic ladder, later becoming an Examining Magistrate in a provincial court. He has sown some wild oats, but with bureaucratic discretion. Then he marries. For no other reason than because in the fitness of things, it is what is usually done by people of his class at his time of life. He enjoys a brief spell of happiness enjoying ‘conjugal caresses, new furniture, new dishes, new linen’. Then after the birth of his first child he sees his wife change to a temperamental shrew. Ivan Ilyich withdraws into his shell, realising ‘that conjugal life, while offering certain conveniences, was actually a very complicated and difficult matter’, that one must ‘put up a decent front to win the approbation of society and, as in a professional career, one must work out definite principles.’

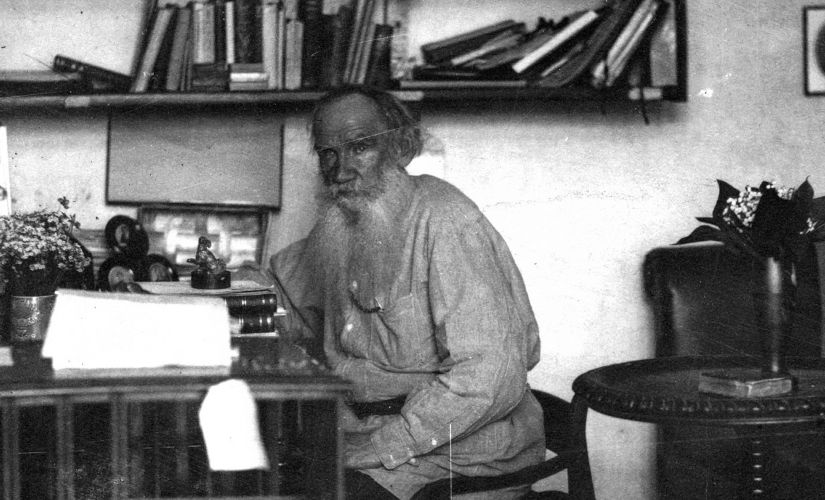

Leo Tolstoy in his office. Wikimedia Commons[/caption] There is only one real solace and that comes from the poor, unlettered peasant boy who comes to help him with his bodily functions, to lift him from toilet seat to bed, to change his position or keep his legs raised in a way that reduces his pain. The boy has a healing touch. Nothing revolts him, no smell or mess or demand is too trying. His great physical strength and his patient kindness in small acts of service to Ivan Ilyich’s dying body bring him in grateful contact with some holy well-spring of living mercy. All he can do is draw comfort and silently bless the boy that he too should have someone kind, strong and caring at his bedside when his time approached. Close to death, largely neglected by his circle and more-or-less reconciled family, Ivan Ilyich realises what his life has lacked – the warm flow of human kindness which alone is worth anything at all. Ivan Ilyich dies. His friends visit. Some frown on sentimentality, some whisper about the post he has vacated, his wife worries over money due to him, the priest and the undertaker get into their act. Of all Tolstoy’s writings, this panoramic story works its wisdom viscerally into the reader’s experience, compelling us to slip into a two-minute silence when it ends – for Ivan Ilyich, for all humanity, for our own narrow self-project that keeps us distracted from the closure that awaits us all. Look out for it and read it. If you’ve read it before, read it again.

Leo Tolstoy in his office. Wikimedia Commons[/caption] There is only one real solace and that comes from the poor, unlettered peasant boy who comes to help him with his bodily functions, to lift him from toilet seat to bed, to change his position or keep his legs raised in a way that reduces his pain. The boy has a healing touch. Nothing revolts him, no smell or mess or demand is too trying. His great physical strength and his patient kindness in small acts of service to Ivan Ilyich’s dying body bring him in grateful contact with some holy well-spring of living mercy. All he can do is draw comfort and silently bless the boy that he too should have someone kind, strong and caring at his bedside when his time approached. Close to death, largely neglected by his circle and more-or-less reconciled family, Ivan Ilyich realises what his life has lacked – the warm flow of human kindness which alone is worth anything at all. Ivan Ilyich dies. His friends visit. Some frown on sentimentality, some whisper about the post he has vacated, his wife worries over money due to him, the priest and the undertaker get into their act. Of all Tolstoy’s writings, this panoramic story works its wisdom viscerally into the reader’s experience, compelling us to slip into a two-minute silence when it ends – for Ivan Ilyich, for all humanity, for our own narrow self-project that keeps us distracted from the closure that awaits us all. Look out for it and read it. If you’ve read it before, read it again.

The Stories in My Life: Leo Tolstoy ponders mismanaged, superficial living in The Death Of Ivan Ilyich

Neelum Saran Gour

• August 13, 2019, 13:20:11 IST

Of all Tolstoy’s writings, the panoramic story of Ivan Ilyich works its wisdom viscerally into the reader’s experience, compelling us to slip into a two-minute silence when it ends – for Ivan Ilyich, for all humanity, for our own narrow self-project that keeps us distracted from the closure that awaits us all.

Advertisement

)

He loses himself in his upward mobility program, works hard, is promoted to Assistant Public Prosecutor. ‘The consciousness of his power, his right to ruin anyone he desired to ruin, the weightiness of even his appearance as he entered the court and spoke to his subordinates… all these things brought him joy..’ He is obliging with social superiors, officious with social inferiors, as he advances in life. Once he loses a promotion and it all but breaks him. He changes his position for a better one, a higher salary and superior perks. There isn’t much of an emotional bond with his family but he rejoices in choosing a beautiful apartment for them, exactly the kind of apartment that people of his class inhabit, and he decorates it with passionate interest, buying all the appurtenances and artefacts that people of his class value and revel in. ‘Precisely what a certain class of people create so as to make themselves like all other people of this particular class.’ The family moves in, delighted with their home and his new position. But when a house is actually lived in, its occupants come to feel that it lacks but one room to make it perfect, just as his new income ‘needed but the least little bit more… to make it sufficient.’ So, going to court, coming home, suffering pangs at every little scratch and dent and stain in his beautifully done-up home, throwing elegant parties, playing cards, moving in the best circles, finding a highly eligible match for his daughter… these things fill up the days until Ivan Ilyich falls ill. A wee bit of discomfort, a strange taste in the mouth, a continuous depression is how it starts. A string of medical specialists spell out technical details about kidneys and caecum, the reports of tests, medicines prescribed and changed and many experimental alternative cures tried. But the pain in his side does not go. He has flaming rows with his wife. He believes he is getting better, only to take a turn for the worse. The weeks turn to months. The devastating realisation comes that the whole thing is not some exercise of theoretical medical formulae about kidneys and caecum but a terminal wager between life and death. And then the excruciating agony of intensifying pain with the certainty of death ahead. The body suffers without respite while the mind tortures itself with panic-stricken speculations about his soul’s future. There is no idea of God left in this darkness and no religion functioning effectively any more. All ideas become deactivated and turn into failed constructs in the dire aloneness of his plight. [caption id=“attachment_7126761” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

End of Article