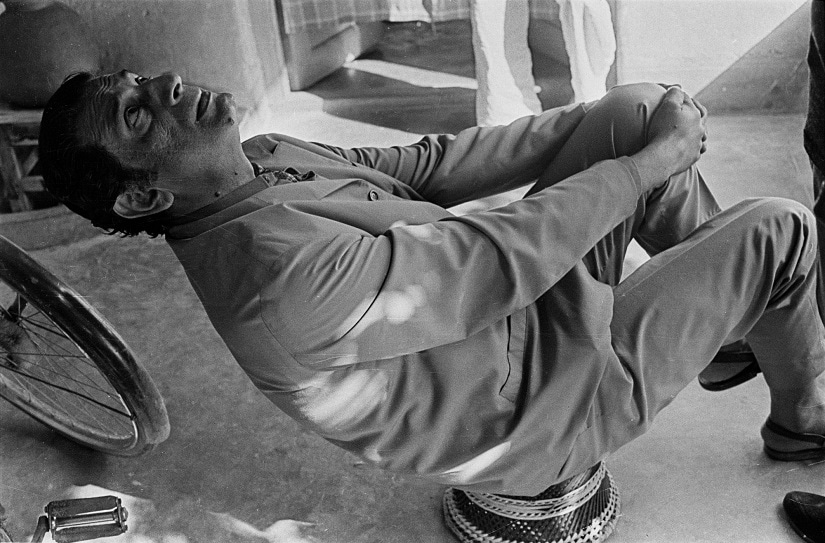

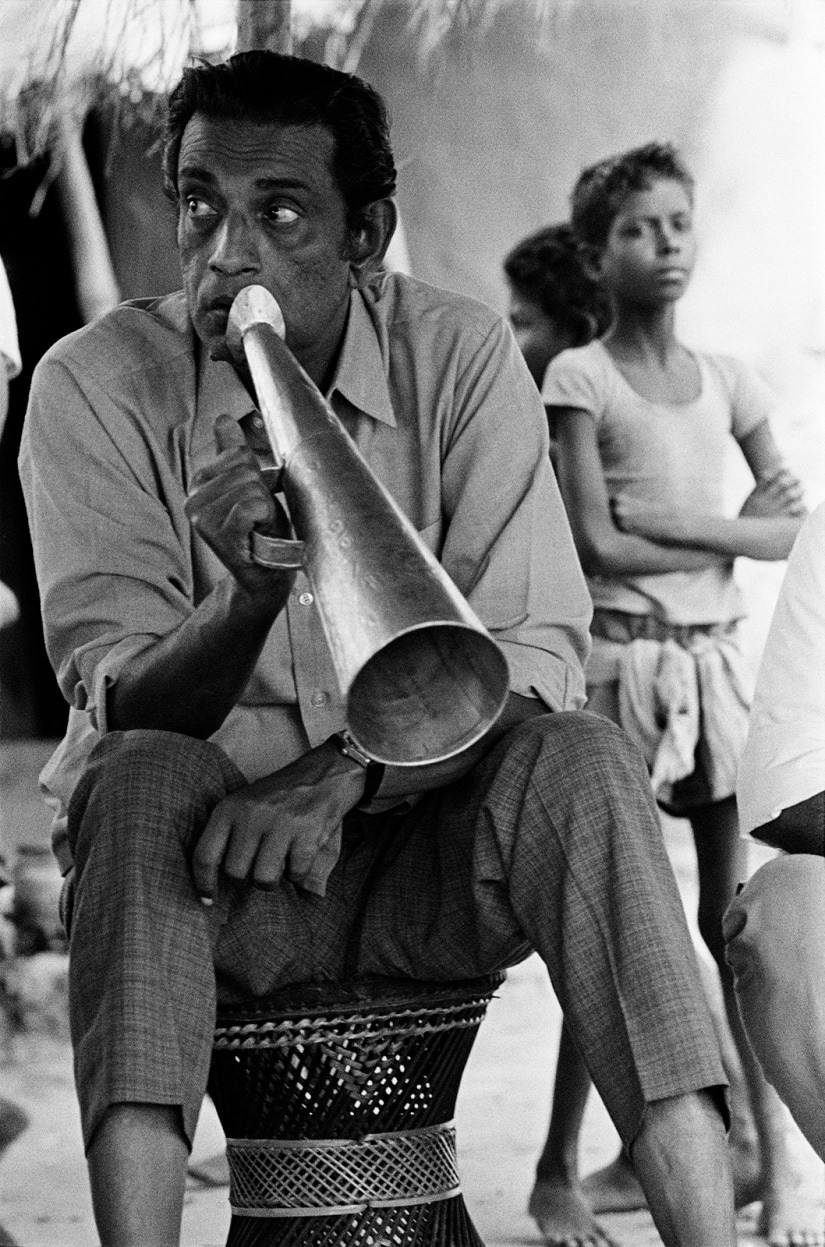

Satyajit Ray is widely regarded as the greatest Indian filmmaker to have ever lived. He is perhaps also one of the least watched Oscar-winning (honorary) directors in the world. Such is the history of our engagement with the arts: We name-drop Husain, Ray, Mangeshkar, Roy and others as if we are personally invested in their craft or would jump at the opportunity to do so, but respect and a studious approach to their work has always been lacking. However, there have been some who have dedicatedly chronicled the movement of genius, of the making and elevation of some of our brightest beacons. Nemai Ghosh, though just as well known for his documentation of Calcutta and other stars of Bollywood, is most easily identifiable for his photographs of the Bengali cultural icon — a man whose reputation has now superseded that of his work. [caption id=“attachment_4478325” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Jana Aranya (The Middleman), 1975. All photographs by Nemai Ghosh[/caption] A fact that many do not know is that Ray started out in advertising. A student who fared poorly at academics, he eventually joined Shantiniketan, and then left abruptly. Very early on, he had begun to write, draw and illustrate books and advertising campaigns. He famously went to Europe where he skipped meals to watch rare films. But Ghosh met Ray when the first blocks of his legacy had already been laid. “At that time, he was already an auteur,” Ghosh says, “and I was an amateur. Later, during the shooting of Aranyer Din Ratri, Sharmila Tagore told me to not to say that I was an amateur, but rather say ’non-professional’. I was in a trance when he called me in and praised my photographs. Not only that, he encouraged to me to pursue photography. That was my very first memory with Ray. That was how my association with him began. His sincerity, honesty, discipline and tenacity attracted me like a magnet. Later I became a regular unit member of his films.” [caption id=“attachment_4478331” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Joi Baba Felunath (The Elephant God), 1978[/caption] Ray’s oeuvre, its earthliness, its departure from convention and its crucial relocation to the fringes of socio-geographic situations have been lauded all over. But while these films earned plaudits and made little money on the side, the struggles involved in completing them were as poetically sombre as their very nature. “Funding has always been an issue with filmmakers, and it was no exception for Ray as well, although no other filmmaker could represent India like him. There had been many occasions where he had to postpone or stop shooting due to lack of funds. Before Gupi Gayen Bagha Bayen he had to wait for one long year, because it required a huge budget to shoot. No producer wanted to put their money on the film. From Ghare Baire to the shooting of Agantuk, nothing would have been possible without the help of the government of West Bengal or the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC),” Ghosh says. [caption id=“attachment_4478337” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Ray on location while shooting The Inner Eye, 1972[/caption] A photograph of Ray sitting at the far end of his motley crew, eating lunch out of a paper plate is suggestive of the sheer managerial task filmmaking was. It wasn’t just about the lens, it was about handling people as well. Even in a photo as candid as this one, Ray is seen facing the wind — giving himself a little space perhaps, to think and plan his next move. He was, after all, in uncharted territory — portraying a side of India that mainstream Bollywood was not interested in showing. “People often misjudge him and his works, accusing him of glorifying the poverty of India. It is misplaced. He always followed his subject religiously and shot meticulously to underline the emotions of the characters, faithful to the context. When he shot Shatranj Ke Khilari, he used exotic landscapes because the subject demanded it. Be it Pather Panchali, Sonar Kella or Hirak Rajar Deshe, he used his landscapes to the peak of perfection,” Ghosh says. [caption id=“attachment_4478339” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Ray on the set of Asani Sanket (Distant Thunder), 1963[/caption] Both Ghosh and Ray have had love affairs with Kolkata. Both brought nativity to its perception — a treatment all colonial cities require. Ghosh also captured some of the rising stars of Bollywood through the 60s and 70s. But no one cast doubt on his most fruitful association, more so because of the trust Ray put in the people around him. “While shooting Shatranj Ke Khilari the producer told Manik Da that it would be convenient for him if a photographer from Bombay worked as the still photographer for the film,” Ghosh says, “Publicity design and promotion of the film would be made a lot easier that way. Manik Da agreed. Others asked, what would Nemai do? Manik Da assured everybody, saying that I would do what I have always been doing. ‘He will capture me.’ Later, the eminent photographer from Bombay failed to match the pace of Manik Da’s work, shook hands with him and left the set. I did all the photography for the film. It was, and still is a moment of pride for me. Such was the charm of Manik Da’s magnanimous personality. I don’t think I would ever be able to put it into words,” Ghosh says. [caption id=“attachment_4478353” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  A still from Ghare Baire (Home and the World), 1984[/caption] The latest exhibition of photographs by Ghosh is a resounding reminder of the need to look at Ray — not just through his films — but as a person attempting to get past challenges, like any of us. Even in his most candid moments, he seems cut from a different fibre altogether. Does he compare with anyone else in the Indian film industry? “Ray’s comparison is Ray himself,” Ghosh says. Satyajit Ray and Beyond is housed by the DAG and will be on show at the Nehru Memorial Museum until 30 May

Nemai Ghosh, who is displaying the candid photographs he took of Satyajit Ray, speaks about how the filmmaker encouraged and mentored him

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)