The old city of Jaipur was recently accorded the status of a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and this recognition of Rajasthan’s built heritage is certainly a reason for celebration. Formal recognition will only aid in conservation efforts and sensitisation. This is then a good time to introspect on the intangible heritage of the state, which is now inches away from extinction. The vehicle of intangible heritage is language, and since Independence, there has been no official recognition of Rajasthan’s language. This means that it is neither a recognised medium of instruction in schools and colleges, nor does it have recognition in the state’s courts or in its Vidhan Sabha. DD Rajasthan is broadcast primarily in Hindi, the local film industry is dead, the Rajasthani print media barely has any circulation. Even the business of gram panchayats, where the medium of communication is almost solely the local language, must be carried on in Hindi.

Rajasthani remains a language that is not associated with any economic opportunity and completely excluded from public spaces, and increasingly, private spaces too.

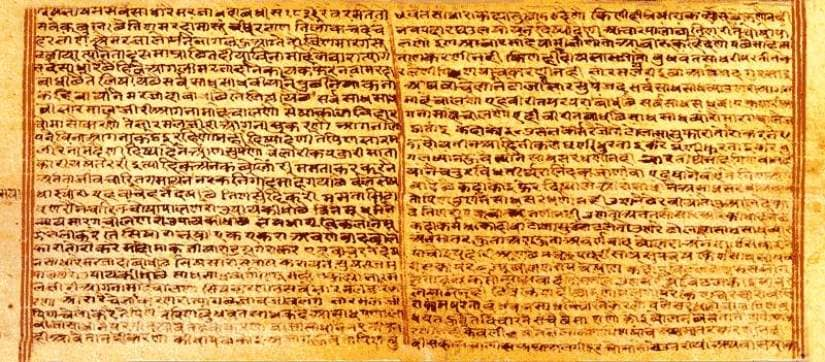

Consider, for example, Rajasthan’s folk music: On the surface, it may appear to be thriving. International festivals which curate the state’s music traditions are rated among the best in the world, its artistes and performers are sought after and perform around the globe alongside other artistes of international standing. However, not looking at the larger picture can be misleading. Shubha Mudgal observed that the repertoire of the famed Manganiars of Rajasthan remains a mere fraction of what it once was. It consisted of thousands of songs, but today, the Manganiars can be found largely singing ‘Sufi’ songs which listeners can jive to, or they participate in ‘fusion’ projects with other music genres, which rely solely on their musicality. Among the thousands of Rajasthani folk songs to be found on Youtube, probably not a single one has been composed within the last 50 years. Most of these centre on shy women — conducting coy romances — who seek the help of the postman or migratory Siberian cranes to deliver their love letters. [caption id=“attachment_7388491” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Representational image. Wikimedia Commons[/caption] The puppeteers in the state, a common fixture in hotels and reduced to being only showmen today, were actually storytellers and genealogists who narrated ballads and histories. The audience for folk music — so heavily narrative in nature — continues to dwindle, as fewer people can follow the lyrics at all. Art forms which do not have a visual or aural spectacle to offer have completely vanished; these include poetry, storytelling and narrative recitals. We are witnessing the ‘fossilisation’ of intangible heritage, caught between ‘Kesariya Balam’ on the one hand, and jam sessions on the other — a process by which this heritage will soon exist only as an anachronism on the one hand, and as exotica on the other. Language has been the rallying point for various sub-national movements across the country. The recent push for the One Nation-One Language model has been met with sharp resistance and criticism from many parts of the country, including Assam, West Bengal, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. Rajasthan, on the other hand, is as quiet as quiet can be. It has been so for seven decades now. The census data on mother tongues (see for example, the Linguistic Survey of Rajasthan, 2011) records that out of a population of nearly seven crore people in the state, 4.75 crore people are speakers of Rajasthani in one of its many forms. How then did a language which traces its origins back to the classical Dingal and Pingal literary traditions end up in this situation? Its close cousin Gujarati is alive and kicking, both in the spoken and written forms. Migrant Gujarati families continue to speak the language, even those settled abroad. Those involved in the campaign for the official recognition of Rajasthani cite various historical reasons for this, ranging from pointing out that at Independence, Rajasthan’s bureaucracy was dominated by Hindi-speaking migrants, to the fact that Marwari business stalwarts who funded and were closely involved with the Independence movement gave priority to Hindi as the language which would unify the newly formed nation. Contemporary interventions by urban Hindi- and English-speaking elites have avoided the issue of language altogether. Chandraprakash Dewal, scholar and writer in the Rajasthani language, says that for 70 years now, generations of students have not had the chance to be educated in their mother tongue. It does not find a place in the three-language formula. Even as this article is being written, the Rajasthan Public Service Commission has advertised for the recruitment of school lecturers. Out of the 5000 vacancies announced, 782 are for Geography teachers, 613 for History, 304 for English, 15 for Punjabi and so on; but a mere 6 are for Rajasthani. At home, a child may learn to call a crow ‘kagla’, but once she begins to go to school, the teacher insists on calling it ‘koua’. In the mind of this child, what is spoken at home becomes an ‘apbhransh’ — a delegitimised distortion, a mere colloquial tongue to be confined to private spaces. It is no wonder then that Rajasthani is now being pushed out of homes too, with parents choosing to speak to their children in Hindi as opposed to the language they inherited from their own parents. It is a testament to the tenacity of oral traditions that Rajasthani in its different forms survives to this day, and that too so widely. There are those who point out that Rajasthani is not one language, but more an umbrella term for a collection of dialects such as Dhundhari, Hadauti, Mewari and Marwari, among others. They add that there is no standardised written form, which is why it should continue to remain a dialect. One response to this argument is that the standardisation of a language usually comes about by institutionalisation within the academy. Many regional languages underwent this process in the 19th and 20th centuries. Barna Parichay, the treatise by Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar, which laid out, in large measure, the foundation for the modern written form of Bengali, was published as late as 1854. Hindi as it is known today is itself a mixture of so many dialects, and its present spoken and written form attained widespread currency only in the years after Independence, when it was positioned as the language which could unify the country, through the effort of writers and scholars such as Hazariprasad Dwivedi and Maithalisharan Gupt. These arguments lead us into the heart of the tension between the ‘folk’ and the ‘classical’, and between the oral and the written. Contemporary discourse has gone beyond the quest for standardised and institutionalised identities. An oral tradition is not a signifier of inferiority. In fact, the vastness of oral traditions can sometimes outweigh written ones in terms of richness. The diversity of the spoken dialects of a language are not a weakness, but in fact its strength. Considering this, what is the need for institutionalisation at all? Is there a need to formalise the recognition of a language whose spoken form is said to change every twelve miles? The answer in how the way knowledge is produced and transmitted has changed. At Independence, Rajasthan’s literacy rate stood at a mere 6 percent. Today, government figures peg the literacy rate at 66 percent. For many centuries, knowledge was mostly transmitted within families and communities, and the site of most learning was the home. Today, that site has shifted to institutions, where the traditional vehicle of knowledge has no recognition. Dularam Saharan, writer and convenor of the Prayas Sansthan in Churu, points out that the fight for recognition is not only a fight of principle. Recognition will almost immediately open up economic opportunities associated with the language. Positions in schools, colleges and universities, allocation of funds for research, formalised language fluency requirements for bureaucratic postings, immediate requirements for translators in the functioning of the government; recognition and opportunities for writers and scholars of the language; a bare minimum space in the print and digital media. The efforts of the linguist Suniti Kumar Chatterji in the 70s enabled the recognition of Rajasthani as a language by the Sahitya Akademi. Almost immediately, the pioneering work of Vijaydan Detha came into the national limelight, enabling its recognition and translation. To this day, the Sahitya Akademi announces an annual prize for Rajasthani literature. This recognition has enabled the survival of a literary scene, however meagre it may be. The benefits from constitutional recognition promise to be wider and bigger. Formal recognition will not solve all the aforementioned problems. The inferiority complex associated with a regional language, aspirations to an identity that is ‘global’ — these are deep-seated prejudices in our minds and societies.

Recognition will, however, give the language of the people of Rajasthan legitimacy.

It will bring the language into public spaces, or at least, the right to be in public spaces. And most importantly, one hopes, it will inspire confidence in its speakers to speak it without shame and embarrassment. We have put forward and won a case for the international recognition of our built heritage. The irony then, of refusing to recognise our intangible heritage in our own nation, is inescapable. The demand for recognition is not necessarily to establish a new hegemony based on parochial regionalism, but rather a demand for the bare and basic legitimacy of our mother tongues, our stories, our songs, our sayings and the centuries of our knowledge crystallised in our language. Kanhaiyalal Sethia, the foremost of modern Rajasthani poets, whose birth centenary we have just celebrated, left us with the line that has become the call of the movement for recognition: Rajasthani binya kyaro Rajasthan! (Without Rajasthani, what is Rajasthan) The current Chief Minister, himself a speaker of the language, hails from a city in Rajasthan renowned for the sophistication with which it speaks Rajasthani. The government at the Centre prides itself on its cultural revivalism. There is an ever increasing recognition and understanding of the state’s tangible heritage. To preserve our oral traditions is to preserve living and mutating strands of the human experience. The fate of these strands now hangs by a thread; we may be the last generation of parents who will speak to their children in the mother tongue. The time is right, and this may be our last chance. Vishes Kothari translates from Rajasthani to English. He was trained as a mathematician and currently works as a financial consultant

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)