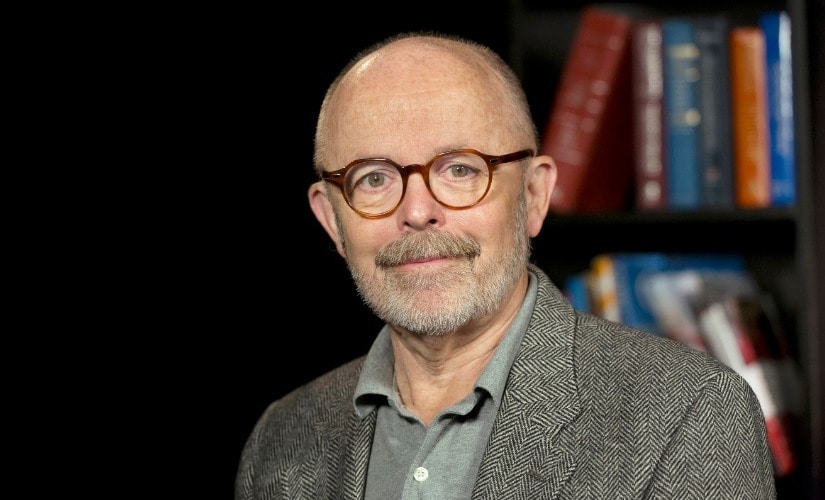

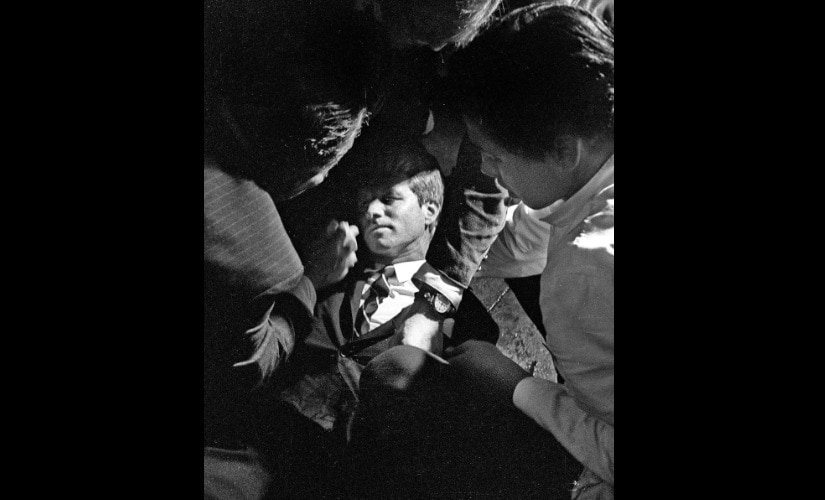

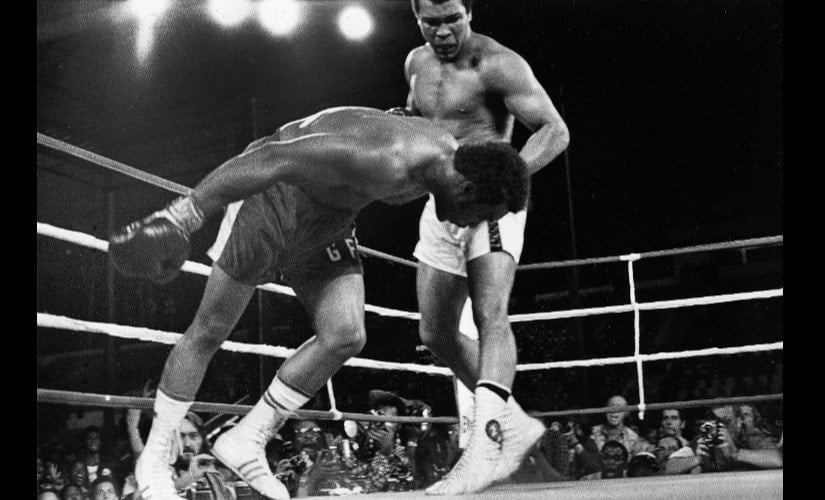

Nearly two decades after he took them, Richard Drew’s photograph of a man falling from the World Trace Centre’s North Tower during the 9/11 attacks draws polarising reactions. The Pulitzer Prize winning photographer, currently in Hyderabad for the Indian Photography Festival, spoke with this correspondent about the fateful day when he shot the image now known globally as “The Falling Man”. Drew was covering the first day of the New York Fashion Week, chatting with a CNN videographer during a break, when the latter received an alert about a plane hitting the WTC. “Seconds later, my editor called and told me the same,” Drew remembers. “She said, ‘Bag the fashion show, you have to go’ and so I did, taking the subway from the Times Square station.” On reaching ground zero, Drew began working on auto-pilot: “My adrenalin was pumping. All I was thinking about was getting the pictures,” he says. “I was so caught up in the moment that when the first tower began to fall, a rescue worker came and pulled me away, saying we had to leave, or we would be crushed. I resisted even as he pulled me forcibly down the street. I continued shooting pictures until he had dragged me to safety.” [caption id=“attachment_7361861” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  The photo known as The Falling Man: A person falls headfirst from the north tower of New York’s World Trade Center, 11 September, 2001. AP Photo/Richard Drew[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_7361871” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  The World Trade Centre collapses during the 9/11 attacks. AP Photo/Richard Drew[/caption] For over 48 hours, Drew focused on the technical aspects of his work and shut down all emotion. He remembers feeling like a robot, and operating on adrenaline — so much so he couldn’t go to sleep at night. His wife later told him that he was up at 4.30 am (the next morning), vacuuming the apartment. “Working nonstop was my way of postponing reality,” Drew says. “I’m told my symptoms were consistent with PTSD. It was several days before the trauma had subsided enough for me to realise the magnitude of what had actually happened.” On the third day, Drew’s three-year-old daughter called him on the phone; she told her father she loved him. Hearing her voice made Drew think of all the people who hadn’t survived 9/11 — who wouldn’t see their children ever again. He broke down. “I walked the five miles home from Ground Zero, carrying my gear, and went to bed for several days,” Drew says. “To this day, my daughter calls me on 11 September — wherever I am — to say that she loves me.” [caption id=“attachment_7361831” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Richard Drew[/caption] The reactions to Drew’s ‘Falling Man’ photo were mixed — some editors withdrew the image from circulation for years, others labelled him ‘unfeeling’. “So many people called in to complain about it to the Des Moines Register, Iowa’s leading newspaper, that the paper’s publisher printed a letter on the front page the next day apologising for running it,” Drew says. It was only two years later, when Tom Junod wrote a 7,000-word article for Esquire magazine examining why the photograph had so upset people, despite the absence of visible or obvious gore in it, that the general opinion was reversed. (Incidentally, it was the article’s headline — ‘The Falling Man’ — that the photo came to be identified as.) Academic dissertations were written on the photo, which has been named among the five most historically significant in the world. What was once considered offensive is now widely accepted as a masterpiece of photojournalism. And yet, the image itself hasn’t changed — only people’s response to it. While he is known most for the Falling Man, Drew’s career as a photojournalist has seen him capture many a landmark moment. As a 21-year-old working for the Pasadena Star-News, Drew photographed the assassination of Robert F Kennedy, just after he won the presidential primaries in South Dakota and California. Even though Drew wasn’t on duty on that night, he’d wanted to be there for Kennedy’s victory. He was on stage as Kennedy gave his speech, then preceded the Democratic candidate into the kitchen. Drew stopped to get a glass of water, Kennedy passed him and was shot. [caption id=“attachment_7361771” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Robert Kennedy campaigns in San Gabriel, California, 21 May 1968, two weeks before he was assassinated. Photo by Richard Drew/Pasadena Star News[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_7361791” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Robert Kennedy lies on the Ambassador Hotel kitchen floor after being shot by Sirhan Sirhan, in Los Angeles, California, 6 June 1968. Photo by Richard Drew/Pasadena Star News[/caption] “I briefly saw the gun pointed at me, and I hit the floor. Shots rang out, chaos ensued. I joined a UPI photographer standing on a kitchen utility table to get a better vantage point for my photography. I remained calm, mentally going into coverage mode to record the events as they happened. The other photographer and I had to hold each other up afterwards as we realised the enormity of what we had just witnessed. We still talk about it to this day. I had to find my car, and drive to the newspaper, where the editors were astonished to learn that I had been there and had photos. My pictures and page one, first-person story ran in the next day’s paper,” Drew remembers. Many celebrities found their way into Drew’s viewfinder: The Beatles (when they arrived in Los Angeles to mass hysteria), Frank Sinatra and Jackie Kennedy Onassis (while out on a date; Drew’s is the only photograph of the duo together), Muhammad Ali (during his “Rumble in the Jungle” fight against George Foreman), Prince. But Drew emphasises that it’s important not to deem any subject, or assignment, as unimportant. [caption id=“attachment_7361801” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Challenger Muhammad Ali watches as defending world champion George Foreman goes down to the canvas in the eighth round of their WBA/WBC championship match in Kinshasa, Zaire, 30 October 1974. Foreman is counted out by the referee and Ali regains the world heavyweight crown by KO in the bout dubbed Rumble in the Jungle. AP Photo/Richard Drew[/caption] “You may take a picture of a minor politician who years later becomes the leader of a country. Or they might get arrested for a horrible crime, and suddenly your old picture is used everywhere. A friend of mine took a picture of OJ Simpson and his wife Nicole at a nightclub that no one cared about when the retired football player was a has-been. Two years later, OJ was charged with killing his wife and led the police on a televised high-speed car chase down a Los Angeles highway, before starring in the most widely watched trial in American history. My friend had the most recent photograph of OJ and his wife together. He lived for two years off the sales,” Drew says. Drew — who has been working as a photojournalist in the eras that saw a transition from black and white to colour and then digital photography — says it’s essential for those in the field to keep up with the latest innovations. What has also helped him? Prioritising resourcefulness over confrontation. “I have a friend who keeps a giftwrapped box — large enough to hold his camer — in the trunk of his car,” Drew shares, and laughs. “When a subject is in hospital, he grabs the ‘gift’, walks right past the other photographers thwarted by security personnel, rides the elevator to the VIP floor, and takes his shot.” His tip for aspiring photojournalists is to keep it simple and straightforward: Befriend the gatekeepers, show up early for events, and Drew says, “Dress nicely. Be polite. It gets you into more places.” — All images courtesy of Indian Photography Festival and Richard Drew

The Pulitzer Prize winning photographer Richard Drew, currently in Hyderabad for the Indian Photography Festival, spoke with this correspondent about the fateful day when he shot the image now known globally as “The Falling Man”.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)