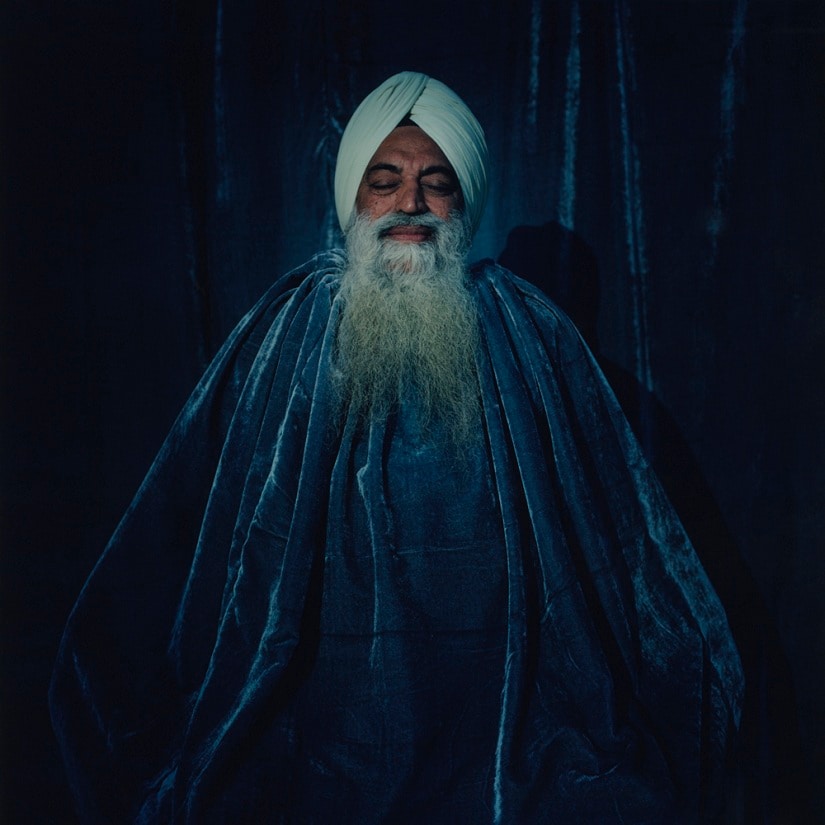

With the emergence and spread of social media campaigns like #MeToo, and #TimesUp, the reality of gender inequality has come to the forefront of political debate — globally. Hashtag autocompletetruth in Dubai exposed some of the horrifying auto-complete phrases seen on Google’s search engine, when terms related to women were searched. From ‘Women shouldn’t have rights’ to ‘Women shouldn’t work’, the sexism of the 21st century world shocked women across more than 100 countries. More than 24 million Twitter mentions uncovered the myth of gender equality in our so-called progressive world. When four women photographers looked into the world of women in Punjab and among the Punjabi diaspora in the Black Country (Wolverhampton, Walsall and Sandwell), UK, for a project titled ‘Girl Gaze’, they found that patriarchy still controls their lives in different ways — the way a puppeteer directs a puppet’s moves — with invisible hands. The hashtag campaigns on the web turn out to be reflections of the processes taking place in the real world. Phrases like ‘Girls shouldn’t do it’, issues like honour killing, rape, honeymoon wives, female foeticide and infanticide continue to plague society. ‘Girl Gaze: Journeys Through the Punjab & The Black Country, UK’ was a photographic exploration of these realities, being showcased at Punjab Kala Bhawan, Chandigarh. [caption id=“attachment_4409459” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Photograph by Jennifer Pattison[/caption] The viewer entered a world of silences — pulled in by the power of unuttered words — of the girls and women photographed and interviewed over a period of 12 months. The pictorial documentation of women’s love, dreams, rebellion, honour, and chudas (ceremonial bangles worn by a bride), their frozen cries and censored azadi (freedom), the life of chores and of their missing numbers in the census reports reflect an increasing tightening of traditional values on their lives. As the male-dominated society fails to grapple with the world changing outside their confines, especially in a foreign country, it turns more regressive towards women. Symbols of honour and izzat acquire social and cultural sanction, justifying women’s repression. The artistic exploration of these processes was layered with history, culture, memory, dreams and demographics. The project was part of Arts Council England and British Council’s Re-Imagine India cultural exchange programme. Under the programme, the artists were awarded funds to engage with local Indian diaspora communities in Wolverhampton, Walsall, Sandwell, and in cities and villages in Punjab. It took another dimension into consideration. “Women photographers are under-represented in India,” said Iona Fergusson, curator of the show. “We wanted to support the mid-career women photographers who often miss out on the funding required for their work to flourish. Each of the four artists (two each from India and the UK) brings their individual interests and distinctive narrative styles to the fore,” Iona added. The four artists — Jocelyn Allen (UK), Jennifer Pattison (UK), Andrea Fernandes (India) and Uzma Mohsin (India) — initiated a dialogue about the social realm through their art, touching upon multiple issues while engaging a wide range of audiences. The Black Country and Punjab Punjab shares a unique connection with the Black Country which boasts of one of the largest Punjabi diaspora populations outside of India. Since their arrival in the 1940s, they created a unique identity in the area, redefining the cultural, economic and social landscape. Despite the mark they have left in India when it comes to history, business, culture and education, the community feels disconnected from its roots. Bollywood films have become the only way to connect with their land of origin, which, unfortunately, offers only romanticised stories about life. The community missed the evolution of contemporary culture back home. The project, they believed, would help stimulate fresh dialogue with the India of the 21st century. The tapestry On a white wall, framed in white, Jocelyn Allen’s photographs of young girls and a few boys seemed playful, on the surface. Her camera allowed the girls to indulge in their idiosyncrasies in ‘You will live in this world as a daughter’. The pictures, as a result, revealed the dichotomies of their lives, which involve hiding and revealing, and the two sides of life, public and private. Allen’s investigation was triggered by the knowledge of the demographic disparity in Punjab, where the child sex ratio was only 846 girls for every thousand boys, according to the 2011 census report. [caption id=“attachment_4409437” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Photograph by Jocelyn Allen[/caption] In Jalandhar, she came across girls from an all girls’ college, who were working towards achieving greater independence through the pursuit of sport. In ‘The Black Country’, she found girls who told her that grandmothers cry when a girl is born in their families, while their brothers and male cousins enjoy greater autonomy than them. Her visual language engaged with the ironies of being a girl born in Punjab. Jennifer Pattison’s photographs carried with them a tangible tenderness. ‘Rice pudding moon and the river of dreams’ was an exploration of a mother’s expression of love for her child, in the form of loris (lullaby) — a practice carried through generations, across seas. The magical quality of her photographs presented the world of dreams a mother invokes, by singing loris. The inspiration to work on loris comes from folklore, especially stories sung by the Bazigar communities, by Sufi saint Sakhi Sarwar and the ones popularised by Bollywood cinema. [caption id=“attachment_4409443” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Photograph by Jennifer Pattison[/caption] In her interviews with the women of the Black Country, she found that most women do not get time to sing loris. Their memory of loris is replaced by Bollywood lullabies. In the magical world of loris, there lurks a shadow; mothers would sing lullabies for the male child, while the girl would be doing chores in the background. The panorama “We understand incidents in connection with the environment, rather than in isolation. We allow this immaterial quality of life to permeate us when we open our histories and politics to someone else’s truth,” wrote Andrea Fernandes, for her project ‘You laugh as much as you cry’. The three-dimensional simultaneous display of her seemingly simple photographs on multiple panels — of uniform houses, solitary park benches, the deserted urban landscapes of the Black Country — engage in a dialogue with the buzzing markets and fertile flatlands of Punjab. This fleeting visual dialogue kept moving in a 24-minute loop of 1,300 photographs, with texts of her interviews with the women displayed. The viewer became a participant, determining their own path through this journey. The panoramic view does not offer a singular truth; it offers multitude of realities — real and imagined. [caption id=“attachment_4409445” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Photograph by Andrea Fernandes[/caption] In ‘Love & other hurts’, Uzma Mohsin wove the narratives of people, places and their histories, with “Phulkari threads of solace”. The display of her photographs and texts was woven like a web on the wall, in a Phulkari pattern (a kind of embroidery practised by women in Punjab). She used archival materials like old family albums, personal letters and found objects, layering her work with history and cultural context. [caption id=“attachment_4409447” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Photograph by Uzma Mohsin[/caption] Uzma likes to involve her subjects in the narrative process. She gave six of the women she interviewed analog cameras. By superimposing their pictures with hers, she conveyed the dualities and complexities of their lives. Her subjects came from diverse backgrounds. There are grandmothers; a girl with her wrists slit several times, juxtaposed with a picture of her with her lesbian partner; a Sikh girl with tattooed hair and arms, in defiance of the traditions; the woman in a skirt and chuda alone on a street. They told stories of resilience and courage, of their quest for a new life. Despite “…Silence of a cold life/ empty house, late night shifts/garam bistar shared by six/ hair short, unsparing hand/locked in my heart, love and other hurts/ The cooking, the cleaning/the foundries, the fears/ the lashes, the loathing/ deluge of tears, rivers of blood/ locked in my heart, love and other hurts…” The artistic interpretations of a reality — well known in the region — lent greater depth and insight. No one left untouched.

Girl Gaze features the work of 2 Indian and 2 British women photographers, who point their lens at the gender inequality in the Punjabi community | #FirstCulture

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)