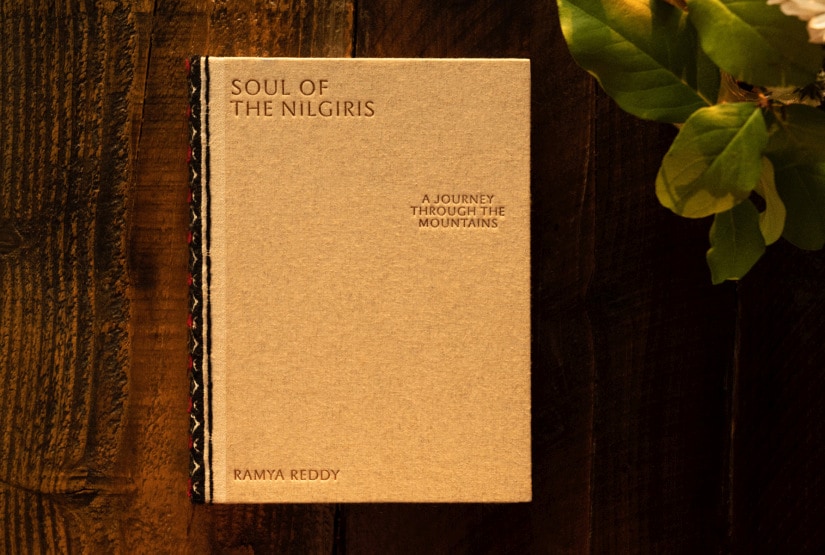

Soul of the Nilgiris, photographer Ramya Reddy’s new book, “is the story of a place told through a personal tapestry of oral narratives, conversations, writings and over 300 photographs — taken over nine years, drawn from the creative abundance of this millennia-old mountain land and her centuries-old inhabitants.” In a conversation with Firstpost, Reddy talks about working on the decade-long project, her interactions with the indigenous people, the intensive research involved, self-publishing, and much more. Q. What was your connection with the Nilgiris and what are your earliest memories there? My connection with the Nilgiris goes back into my childhood. Nippy weather, misty days, and the freedom to wander about on my own, the attachment was natural. So much so that growing up, holidays meant a possible escape into the mountains. There was the golden mountain light that drew the photographer in me there and became one of the inspirations for this project. I came back to study photography and later began to explore the mountains with my husband Rajesh and mountain-loving dog, Yogi. [caption id="" align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  An elder. From Ramya Reddy’s Soul of the Nilgiris. All images courtesy of Ramya Reddy[/caption] Q. Did you start looking at the region differently once you knew your project was going to be a book? For one, I made the transition from wanting to take pretty pictures to tell stories with pictures. Sometimes, I didn’t shoot at all and just listened — to the people, to the mountains, to the sounds of the forests. This was important in not just building real relationships, connections and trust but also sharpened my seeing process and brought more sensitivity into it. Q. How did you go about your research for Soul of the Nilgiris? Much of what is in the book came from my personal interactions with the indigenous people. Transcribing these interviews and conversations gave me a lot of prompts for writing too. I was very lucky in that I had mentors who are eminent Nilgiris conservationists, historians and writers whose guidance informed my research and the course the book significantly. Needless to say, over the years, I read almost every possible book, academic journal and paper on the Nilgiris I could lay my hands on or had access to. These were very important in that they gave me a basis with which to work and understand the context and the people better. While I depended on the many books, online resources and the guidance of my mentors, I stayed in constant contact with the members of the indigenous community. There was so much wisdom coded into these interviews and the more I listened and tuned in, the more I could draw out the essence of these exchanges. While I have tried my best to present their narratives as faithfully as possible, I have also made all efforts to verify broader claims. [caption id="" align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Honey hunters. From Ramya Reddy’s Soul of the Nilgiris[/caption] Q. What are some of the most fascinating things you discovered about them (the communities) during your work? I am constantly amazed at how perceptive, intellectually astute and sensitive the elders are in a quiet way that gives them an almost otherworldly presence. The native elders have long been able to predict the weather by observing subtle signs, using intuition and experience. For a long time, Toda elders predicted the onset of the monsoon with stunning accuracy. However, with drastic changes in climate and environmental degradation, the monsoons themselves have become unpredictable. The honey-gathering Kurumbas and Irulas maintain that honey can be harvested only at specific times in a year. Harvest quotas are restricted based on the ecological health of the region in the given season. Once again, these understandings, passed down generations over thousands of years, are embedded in the songs and stories of honey gatherers. The Irulas had simple, scientific methods to avoid crop damage by birds, weeds, and insects. They grew natural repellents with the crops, and sowed and harvested in conducive seasons. What also struck me was that they have the gift of an expansive perception of time, they live their lives slowly and fully with a sense of history that goes back many centuries and a sense of the future that one is responsible for. Q. Why did you choose to self-publish the book? How do you classify your book and do these classifications bother you? The process of self-publishing was challenging but very engaging because you have complete control over the final output. You have the full opportunity to live out your vision and this was important because I had nurtured this project over many years and if it didn’t turn out the way I had envisioned it, it would be a pity. My husband Rajesh and I took the hard call to self-publish because there was a fundamental mismatch in the vision of the publishers (who were interested in publishing the book) and how I had envisioned it. Around 30 women from the Toda community became involved and over two years, they hand-embroidered the spines for all books. Almost every spine is unique. Integrating this element, for instance, was a no-no for those who showed interest in publishing the book. Regarding the classification, I hear the word ‘coffee-table book’ a lot and ‘non-anthropological’ too sometimes. An anthropologist told me — without even asking to read — “nice pictures, but book reviews may not take on this book since it lacks anthropological basis.” He may be right and it bothered me at first, but it doesn’t anymore. This book is not an anthropological record but a personal chronicle of experiences with the land and the indigenous people from a region in India that requires anthropology as one of the moving parts to communicate the context and subject with clarity. Anthropology is not the essence of the book, and that helps to ‘un-slot’ it in my mind. The book is about the authentic spirit of a place and its people. [caption id="" align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Bride. From Ramya Reddy’s Soul of the Nilgiris[/caption] Q. Why did you decide to write yourself and what was the process? Did it affect your gaze as a photographer? I like to write and I felt I had to tell the stories in my own voice. They say photographs need no words but writing helped me see better. It has a way of clarifying and opening up new avenues of inquiry and enriching the seeing process. Images and words can have a powerful synergy. Throughout the process of making this book, writing and photography fed off each other. Q. Nearly a decade in the making, is this how you planned it? I hadn’t planned on any timeframe really. It was a research-intensive project and I just let it flow. But what was incredibly interesting is that I started working on this project, slowly, just after the last Kurinji cycle, about a decade ago. This cycle — which I thought I would never see — coincided serendipitously with the project’s completion. In fact, the last image I photographed for the book was a hill swathed in Kurinji blossoms. [caption id=“attachment_6274001” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Kurinji. From Ramya Reddy’s Soul of the Nilgiris[/caption] Q. You speak of several subjects including indigenous communities and the ecological degeneration of the region. What is the larger objective of your work? Lots of anthropological and scholarly work on the Nilgiris has been done over several decades by anthropologists, linguists and historians. In that regard, Nilgiris has been very well represented. However, I believe the real story of a place has to be told through the stories of the indigenous people in their voice, with their narrative and sensibilities, for it to touch a larger audience in a comprehensible way. My objective is to help people connect with the region in a deep emotional sense. Perhaps we can start by opening ourselves to other ways of living and alternative ways of seeing the world. We can learn from the indigenous people, and include some of their cultures and symbiotic practices in our mainstream education. Q. What according to you would be the key takeaways for a reader? The stories, knowledge, and world views of indigenous people answer urgent questions about long term sustenance. Sadly, aboriginal societies with subsistent levels of production are seldom a part of the mainstream culture of their country. Although they contribute to its cultural wealth, they are invariably pushed to the side to make way for a version of progress we have all unimaginatively given into. The rich diversity of humanity, our world views, and unique perspectives contribute to our collective human experience. As anthropologist Wade Davis explains, this is not to suggest that we mimic the ways of the indigenous people, but simply recognise that our way of thinking is just one of many that emerged from one set of historical and cultural circumstances. *** [caption id=“attachment_6273971” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Ramya Reddy’s Soul of the Nilgiris[/caption] The following is an excerpt from the book — Dreams of a Primordial Forest. Almost every time I hiked around the Sholas, my adivasi companions would invariably point to a grove, peak or piece of sky, and launch into a folktale. Initially, I considered them fairy tales or moral stories. But gradually, I learnt that to the communities, they were the stories of genesis, as real and layered as the bed of leaves we were walking on. Stories hold great power. Personifying a tree as a grandfather meant you would never have the heart to bring an axe to it. Not only did these folktales evoke an urge to protect so alive and personable a forest, but they also created a humbling mystique about nature. You can never know all, it seemed to say. In the millennia-old mountains, a human was but a flailing infant. *** Ramya Reddy’ Soul of the Nilgiris is available on www.soulofthenilgiris.com

Soul of the Nilgiris, photographer Ramya Reddy’s new book, “is the story of a place told through a personal tapestry of oral narratives, conversations, writings and over 300 photographs — taken over nine years, drawn from the creative abundance of this millennia-old mountain land and her centuries-old inhabitants.”

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)