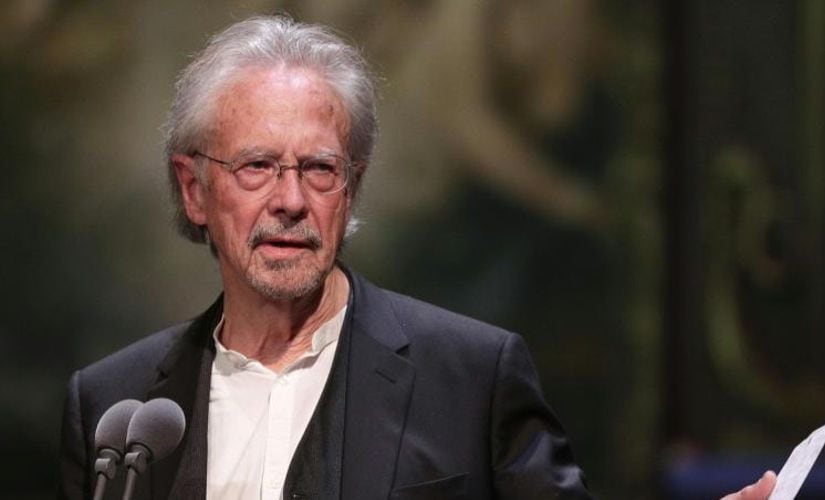

The Swedish Academy just can’t get it right, it seems. The Jean-Claude Arnault affair, which saw the Nobel Prize in Literature being postponed last year, is still fresh in public memory — Arnault, husband of Academy member Katarina Frosterson, lost an appeal against his sexual assault conviction just five months ago, in May. Also, it came to light that Arnault and Frosterson had leaked the names of past winners on several occasions, so that their friends could profit off winning bets. So when it was announced that the Prize was resuming this year, with not one but two Laureates (one for 2018), one assumed that the Academy would seek to repair its image with its choices. Instead, they picked Peter Handke as one of the winners (Polish writer Olga Tokarczuk, who also won the Man Booker International Prize in 2018, was the other). The prolific 76-year-old Austrian writer is known for his experimental plays and novels — and collaborating on several screenplays with the German director Wim Wenders, most notably the acclaimed 1987 film Wings of Desire (later remade into the Nicolas Cage/Meg Ryan starrer City of Angels aka the film for which The Goo Goo Dolls wrote the song ‘Iris’ ). Unfortunately, Handke is also known for being an apologist for Slobodan Milošević (1941-2006), President of Serbia in the 1990s and one of the most infamous war criminals of all time, dubbed “the Butcher of the Balkans”. [caption id=“attachment_7490871” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Peter Handke. Photo credit: Facebook @ROLOFFPETERHANDKEPAGE[/caption] In 1996, Handke wrote a series of essays, later collected in a book called A Journey to the Rivers: Justice for Serbia, where he claimed that Serbia was the real victim of the Yugoslav Wars. Later that year, in an article for a French newspaper, he condemned Serbia’s critics, comparing them to “Pavlov’s dog”. Handke wrote: “Let’s stop associating the ‘snipers’ of Sarajevo blindly to the ‘Serbs’. (…) And stop attributing the rapes to only Serbs. And let’s stop connecting the words unilaterally, like Pavlov’s dog.” He even delivered a brief eulogy at Milošević’s funeral in 2006. Significantly, his defence of Serbia’s war crimes follows a script quite similar to say, a diehard Trump defender today — “both sides” of the story aren’t being heard, the media is biased, liberals are lying for political gains and so on. As expected, not long after the Academy’s announcement, strongly-worded criticisms started pouring in on social media, from readers and writers everywhere. Among them was novelist Salman Rushdie, who tweeted that he “had written about Peter Handke’s idiocy twenty years ago”. The essay that Rushdie was talking about, Moron of the Year, is part of the 2002 collection Step Across The Line. In true Rushdie fashion, it begins: “In the battle for the hotly contested title of International Moron of the Year, two heavyweight contenders stand out. One is the Austrian writer Peter Handke, who has astonished even his most fervent admirers by his current series of impassioned apologias for the genocidal regime of Slobodan Milosevic; and who, during a recent visit to Belgrade, received the Order of the Serbian Knight for his propaganda services. Handke’s previous idiocies include the suggestion that Sarajevo’s Muslims regularly massacred themselves and then blamed the Serbs; and his denial of the genocide carried out by Serbs at Srebrenica. Now he likens the NATO aerial bombardment to the alien invasion in the movie Mars Attacks! and then, foolishly mixing his metaphors, compares the Serbs’ sufferings to the Holocaust.” Nobody — certainly not Rushdie, who expressed his admiration for Wings of Desire later in the same essay — is claiming that Handke’s work is inherently unworthy. On the contrary, Handke’s short, intense novels, like The Left-Handed Woman (1976), The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick (1970), Across (1980) and Don Juan: His Own Version (2010), have received universal praise. These are provocative books — Handke’s existential protagonists often find themselves, a la Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov, committing sudden and horrific acts of violence. In Across, for example, the narrator Herr Loser, a mild-mannered professor of ancient languages who playfully refers to himself as a ‘thresholdologist’, chases and kills a man who he catches inscribing a swastika into a tree. In The Goalie’s Anxiety… the titular goalkeeper Joseph, upset at conceding a goal without even trying to save it (he was sure the referee was going call offside), picks up a woman near a motel. Soon, rough sex escalates into flat-out violence until Joseph murders the woman. Neither of the unlikely murderers faces up to what they’ve done, there’s no regret to speak of. Neither faces comeuppance in the conventional sense, too. And yet, the act changes them at a visceral level — Handke brings this out in deceptively written conversations that feel mundane, but unpack a kind of dream logic beautifully. Handke is thus different from other controversial European writers like Michel Houellebecq, for example, whose works are as misogynist and Islamophobic as the author himself. And yet, his win is a major misstep for the Swedish Academy. After the initial wave of criticism it received over Handke, the Academy claimed that a writer’s political views are not part of its mandate. They seem to have forgotten that Alfred Nobel wanted the prize to go to “the most outstanding work in an ideal direction” — in other words, he wanted to seek out idealism. Now, one may argue that more than a hundred years down the line, the Academy has leeway to chart its own path. But it’s a bit rich of them to claim political neutrality when Nobel’s words explicitly contradict any notions of being ‘neutral’. Instead of cribbing about the backlash, they should have picked a worthier candidate than Peter Handke — it’s that simple, really.

Instead of cribbing about the backlash, the Swedish Academy should have picked a worthier candidate than Peter Handke.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)