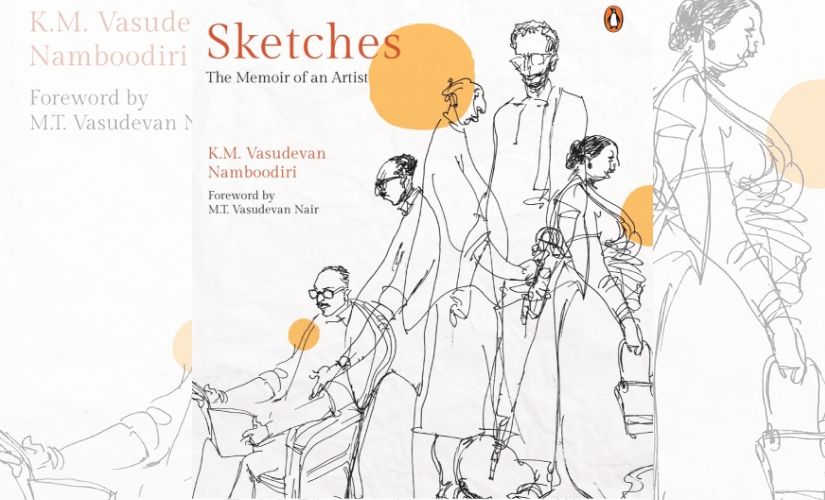

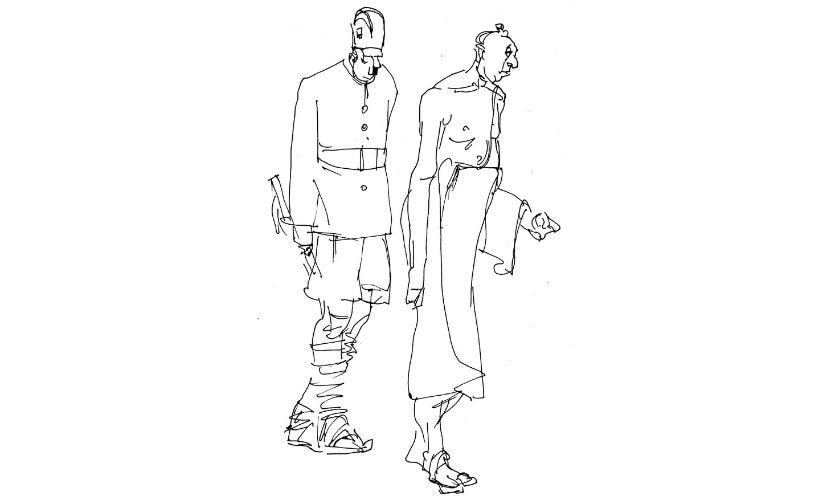

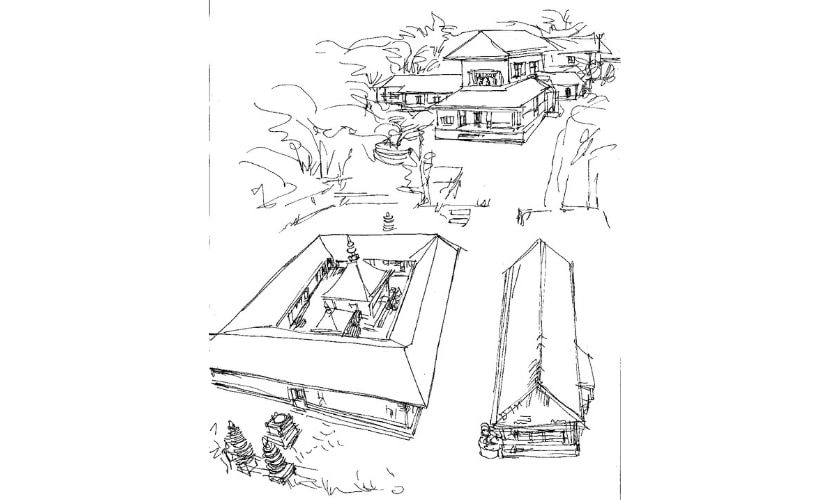

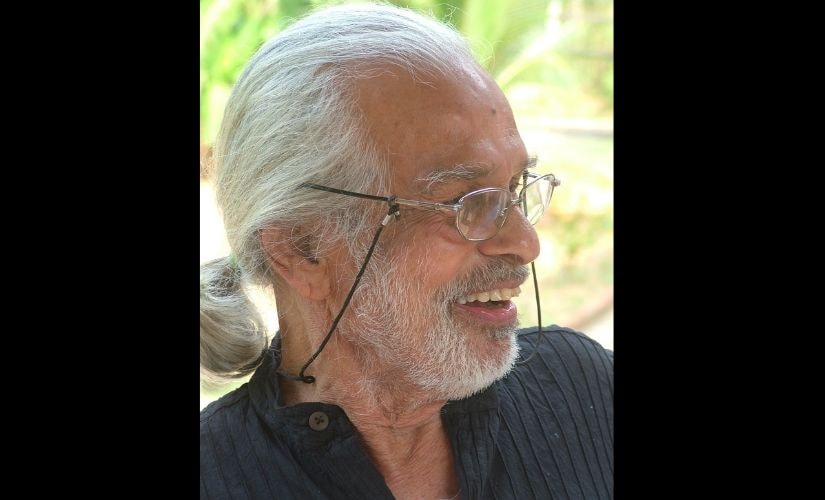

Recreating the charm of 20th century Kerala and its artists is Sketches: The Memoir of an Artist_, the intimate memoir of renowned artist, illustrator, and sculptor KM Vasudevan Namboodiri, better known as Artist Namboodiri. The book is interspersed with his sketches and translated for the first time into English by Gita Krishnankutty, with a foreword by MT Vasudevan Nair._ In Sketches Namboodiri recounts his life and the people that populated it, starting with his childhood and vividly portraying rural Kerala and describing community spaces that were centres of creativity and a place for cultural exchange. He also chronicles his time as an art student, having studied painting at the Madras School of Fine Arts and being a disciple of the renowned artist KCS Panicker, offering glimpses into the worlds of art and literature at the time. Related with humour, charm, and wit, Sketches is a visual and literary narrative of the life and times of the eminent artist in his own words. Today, on the occasion of his birthday, below is an extract from the book’s first chapter Ponnani_._ Sketches: The Memoir of an Artist by KM Vasudevan Namboodiri is published by Penguin Random House India and the following excerpt has been reproduced here with due permission. [caption id=“attachment_7333681” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Book cover of Sketches: The Memoir of an Artist by KM Vasudevan Namboodiri. All photos courtesy Penguin Random House India.[/caption] *** The most important temple in our village was the big Thrikkavu Temple that belonged to the Samoodiri of Calicut* — perhaps it would be more correct to say that the Samoodiri had acquired it, purely through his position of authority. It was surrounded on all four sides by madoms where Palakkad Brahmins lived, and samooham madoms, the community centres where they conducted their social and religious functions. The precincts of the Thrikkavu temple were, for us, a family space. I do not remember our house, which we had to move out of when we became involved in a lawsuit with the Chalappuram Bank; we eventually lost the case. What could have been the reason for this but mismanagement? The bank continued to operate for several days in our old house. We moved from there to Kannan Thrikkavu, and our illam, which is what the residence of a Namboodiri is called, now stands there. There is a temple there as well, the Kannan Thrikkavu Shiva Temple. Our present residence must have been the renovated madom where the chief priest lived. [caption id=“attachment_7332961” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Illustration from Sketches.[/caption] The deity of the Thrikkavu Temple is Durga and the temple is well known for the Navaratri festival during which a grand feast is served. This festival boasts of not just one but six or seven chatussathams, during each of which a hundred coconuts are used to make the payasam that is served to the deity as naivedyam. Besides coconuts, this payasam contains jaggery, rice and a small, sweet banana called kadali. On all nine days of the festival, the percussionists perform two or three thayambakas, solo performances on the drum that last for one or two hours. All the celebrated drummers in Kerala come to perform. Malamakkavu Keshava Poduval, the maternal grandfather of Thrithala Keshavan, who is now a well-known artiste, comes regularly. His younger brother, Achutha Poduval, is a brilliant player. A thayambaka as splendid as the one they perform cannot be imagined. The audiences are extremely appreciative and there are often excellent performers among them. The temple no longer serves a feast, as they used to in the old days. It was served in several places: first within the temple, then in the community hall. The Saits and the Brahmins competed with each other to serve the best meal. Each community would undertake the arrangements for an entire day. With each day, the feast would become tastier and more elaborate. The Saits, who were Gujarati merchants, were different only in the clothes they wore; in all other aspects, they were exactly like Keralites. They traded mainly in coir, copra and pepper. They had large tracts of land filled with coconut palms. They spoke a language that was quite different from Hindi. The men spoke the Malayali Muslim dialect, while the women spoke the pure Malayalam of the Valluvanad region. This was because they had each adopted the speech of the particular group they mingled with. [caption id=“attachment_7332971” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Illustration from Sketches.[/caption] Ponnani was a harbour from olden times and that was how several people, including Tamil Brahmins who favoured trade, came to make a home there. Another reason people frequented the town was because there was a court in Ponnani. The Brahmins were also the first high-school teachers in that area. The first headmaster was a Tamil Brahmin — a Swami, as we called them. They taught science and mathematics. Communities like the Variers came as teachers much later. Many Tamil Brahmins left the place after a while, to go to towns like Palakkad and Madras. The Canoli Canal is a cultural phenomenon. It passes through Ponnani and reaches Vadagara, cutting through stretches of backwaters and rivers on its way. There is a tributary of the Bharathappuzha that flows to Tirur by way of the Ponnani bazaar. Houses in which very poor, goodhearted Muslims live crowd it on both sides. The Hindus live on the east of the canal, the Muslims on the west. This region has always been densely populated. The Canoli Canal goes through Andathode, the village that KCS Paniker belongs to, by way of Chavakkad. People used to go this way by boat to Guruvayoor in the old days. They had to walk a short distance after getting off the boat. The Namboodiris of northern Kerala always used this route. My illam used to be a midway place for them to rest awhile, there being no other illams on that route. People would start arriving at our house by evening. They came that way for various reasons — some needed to settle matters in the court or meet a lawyer, others wanted to clear doubts about their legal affairs with Father. Namboodiris were involved in numerous litigations in those days. The Canoli canal was part of the waterway to Thiruvananthapuram. Namboodiris going for a murajapam, a fifty-six-day-long festival held in the Padmanabhaswami Temple in Thiruvananthapuram, went by this route. They usually went in two groups; one was that of the Azhvanchery Thambrakkal, the chief of the Namboodiri community, and the other was that of the Thirunavaya Vadhyan, who is the officiating priest for all ceremonial occasions, as well as a teacher of the Vedas. Both groups arrived in Thiruvananthapuram as guests of the state. A royal messenger was sent from the palace to escort them. The murajapam held in the Padmanabhaswami Temple was a great festival for all Namboodiris. Held once in twelve years, the feasts were its highlight. There was a rule that the Namboodiris had to be given whatever item of food they asked for. Many jokes came to be associated with this practice. The Namboodiris of northern Kerala visited Travancore only for a murajapam and had no other connections with that state; Travancore was another country to them. My elder brother went once or twice, journeying through canals, rivers and backwaters in turn. On one of those occasions, while returning from Thiruvananthapuram, he received the news that the boat that had left just before the one he had taken had capsized — it was named Redeemer, in which the poet Kumaranasan was travelling when he died. [caption id=“attachment_7332981” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Illustration from Sketches.[/caption] People on their way to Guruvayoor alighted from the train at Tirur and came by boat to Ponnani. Or they went on a CC Brothers bus to the Chamravattam river, crossed the ferry and took another bus. All those who halted at our illam would have an oil bath and then be served dinner. A huge pot of rice was cooked for them and a vegetable curry with a very watery gravy. The Namboodiris who came to our illam seldom spoke to one another but this was not because they were unfriendly. The most they would ask each other was, ‘Where are you from, Namboodiri?’ We heard the names of innumerable illams in this way — such as Kasargode in north Kerala — new as well as oft-repeated names. I remember an amusing incident. One of the Namboodiris became entangled in a lawsuit involving a promissory note and landed in jail. The police treated him with great respect since he was a Brahmin. They escorted him to our illam for lunch every day. He would first have an oil bath, then go the temple and chant the Gayatri mantra a hundred and eight times and perform elaborate worship. Ultimately, he would be very late for lunch. Father would wait patiently for him at the illam and eat with him no matter how late he was. Father himself would serve him, then sprinkle water around his own banana leaf and sit down for lunch as well. ‘So you’re going to eat, Karuvadu?’ The Namboodiri would ask Father at this point. Karuvadu was the name of our illam. ‘Yes.’ ‘Now who will sprinkle water around my leaf after lunch?’ ‘You could always use your left hand to do so.’ ‘I’ve never done that.’ And he had just come from jail! ‘Well, you can start today,’ my father would retort. This became an oft-told story among the Namboodiris. If someone had to do something he had never done before, he’d be told, ‘Well, you can start today.’ [caption id=“attachment_7332991” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Illustration from Sketches.[/caption] We knew another character named Dishi Raman — Dishi was the name of his illam. He was known as a mattideshakkaran, which is what people who belonged to Mezhathur or Thrithala were called. It was a derogatory term. VT Bhattathiripad, the well-known Namboodiri reformer, was called one as well. Mattideshakkarans were believed to be ugly. Even the names of their illams were deliberately mispronounced. Dishi, for instance, would be transformed for a joke into Patheelu or something like that. To catch sight of Dishi Raman was considered an evil omen. If someone cut his hand or fell down, people would say, ‘Dishi Raman must be on his way here.’ And the poor man would arrive! He was tall and very old, with sunken cheeks and a long, dark face. He carried several bundles and a stick. He wore a shirt and something that looked like an old coat over it. He would hold both edges of his dhoti tightly as he walked. He was a magician of sorts and rumoured to know black magic. Altogether, he looked a bit like the red-bearded villain in Kathakali. He usually came our way to conduct a lawsuit. Kullan Subramanya Iyer (known as ‘Kullan’ because he was short) was his lawyer. People said most of the lawsuits were to do with fraudulent money transactions. Dishi Raman always came directly to Karuvadu. He would spend most of his time in the dining hall of the temple. He’d have a long bath and then perform worship. It was said he always did things the wrong way round and that he performed the thevaram, the ritual of worship performed for household deities, as if it were black magic. No one dared watch him, we children were afraid to even go that way. Dishi was a dashasandhi, a harbinger of evil fortune. Did he ever clean his teeth or wash his clothes? I do not remember seeing him do so. Not that I’m implying there’s any harm in that. An evil omen of some kind was always associated with Dishi’s arrival. An odour of asafoetida clung to him; he had a store of it in his bag. Besides this, he carried onions, red chillies and other spices he would need with a meal. He would set out all of these before he ate. Cooked food would be sent from our illam — rice, gravies and vegetables—and either Father or one of us would serve him. He always arrived late for lunch after his visits to the lawyer. If Father had eaten by the time he arrived, he would chide him: ‘So you’ve already had lunch, Karuvadu?’ Father seldom gave him occasion for this accusation. [caption id=“attachment_7333001” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  KM Vasudevan Namboodiri[/caption] He visited us often, sometimes staying for a week at a time. He spoke only to Father during this period. He always behaved authoritatively, but Father never said anything to displease him, it was his way to tolerate everything Dishi did. Father actually made up a verse, the gist of which was: ‘I am the hero who has never said an impolite word to Dishi Raman.’ A great title indeed! Visitors to our illam who had not come in connection with lawsuits were usually bound for Guruvayoor. They would first have a bath, then lunch. After a short nap, they would eat dinner and continue their journey. A huge boat would be waiting near Kutti Vaidyar’s bridge over the canal. They would get into it and go to sleep. The boat left at ten o’clock at night and reached Chavakkad early morning. They would walk from there to Guruvayoor. I have often travelled by this route. Most of the time, the boatmen did not have to row at all. Holding on to the oars tied to both sides of the boat, they would walk along the canal. There was no direct bus to Guruvayoor. There was a boat service for some time but it folded up because the sandbank gave way. Only the Canoli Canal endured. *Samoodiri is the hereditary title of the rulers of Kozhikode (Calicut) and the surrounding territory in Malabar, Kerala. The English rendering of Samoodiri is ‘Zamorin’.

Sketches: The Memoir of an Artist is the intimate memoir of renowned artist KM Vasudevan Namboodiri. The book is interspersed with his sketches and translated into English by Gita Krishnankutty.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)