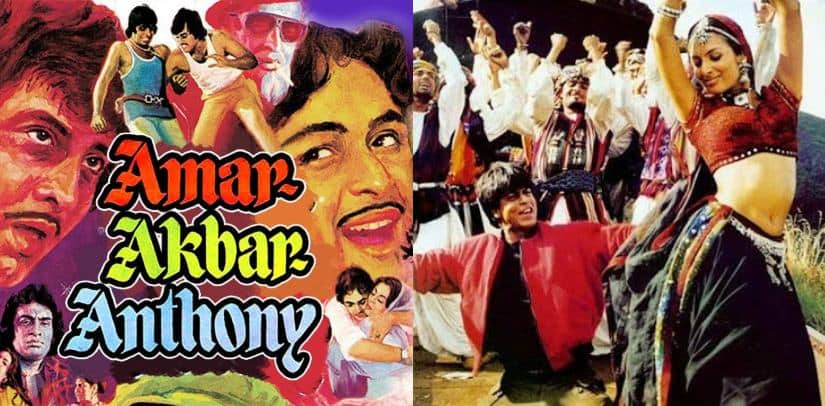

If you turn up your nose at masala movies, Jonathan Gil Harris may have a thing or two to say to you. Jonathan Gil Harris, PhD, is professor of English at Ashoka University. He is, perhaps, better known as the author of the book Masala Shakespeare: How a Firangi Writer Became Indian. Harris is also a champion of masala Indian movies, and says they reflect the idea of pluralistic India, an idea that is under attack from fanaticism. As this type of movie nearly vanishes from our theatres, Harris speaks to Firstpost about his love for masala movies, how the disappearance of these movies parallels growing communalism in Indian society, and how not all is negative about the ‘item number’ song. What are the historical forbears of masala cinema in India? You speak of sangeet natak, I think, in this connection? Yes, the most obvious ancestor of masala cinema is the sangeet natak that the Bombay Parsi theatre produced in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Like its filmi descendant, the Parsi sangeet natak was a mixed entertainment — it blended tragedy and comedy, shayari and gaali, dishoom and naach-gaana, stories from Kalidasa and Shakespeare — and was staged for a mixed audience that crossed many communities and languages. But this investment in mixed styles wasn’t unique to the Parsi theatre. So many forms of ritual and performance throughout the subcontinent mix up sacred and profane, religious and everyday, high and low. Whether it is a Ramlila play in which gods are played by Muslim as well as Hindu villagers, or a cross-communal Holi celebration that mimics Krishna and Radha’s dance as an instance of both earthly and divine love, or a theyyam ritual in which a lower-caste actor becomes a god for the duration of the performance, we find numerous popular traditions that mix the low and the high. And we might mention, in this context, deliberately syncretic rituals such as the Urdu mushaira, in which divine poetry and earthly pleasures commingle, or even Kathak dance, which seems to have begun as a Mughal experiment in blending elements of Persian Muslim and local Hindu cultures. All these have left their imprint, no matter how indirectly, on masala cinema, which — unlike today’s more ‘modern’ film styles — venerates stylistic impurity, the congress between the divine and the mundane. Little wonder that the experience of seeing a masala movie — paying money to sit with a highly mixed audience in a single-screen cinema hall, screaming and swooning and throwing coins at the stars as they make their first on-screen appearances — is both a profane and a religious experience simultaneously. You have a definition of ‘masala’ in cinema. What is a masala movie according to you? For me, a masala movie is any desi movie in a mixed style for a mixed audience in a large cinema hall. We have come to associate the genre largely with the movies of the 70s and the 80s, and with Manmohan Desai’s escapist blockbusters in particular. But his films use the same mix of elements that we find in Hindi movies from previous decades, and in the sangeet natak of the Parsi theatre. Masala movies don’t have to be ‘Hindi’, by the way. Many of the best masala films I have seen come from other regions of India, particularly the south. Any film that combines laughter and tears, that interrupts its dialogues with music and dance sequences, that celebrates a multiplicity of styles and languages and communities for an audience that itself traverses rich and poor, male and female, high and low caste, Hindu and Muslim (and Christian and Sikh and Jain and Buddhist), is a masala film in the most literal sense of ‘masala’ — a mixture. [caption id=“attachment_6102741” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Amar Akbar Anthony, Dil Se. Youtube screenshots[/caption] Why does masala cinema exist in India? Does it exist in other countries? That it exists here has to do with the extraordinary cultural mixtures that we find throughout the subcontinent. It’s not just that India is so astonishingly diverse. Syncretism — the fusing of different traditions — also has a long history here. But something like masala exists in other parts of the world too. Shakespeare’s entertainments are also invested in mixture, and for similar reasons: He was writing not just for the popular theatre, but for an audience that spanned classes, religions, and even dialects, so he gave them tragedies with clowns, lofty poetry alternating with gutter slang, and lots and lots of song and dance. What are the ingredients of a masala movie? What are the quintessential examples of masala cinema in India? I’ve mentioned the specific mixed stylistic ingredients — tragedy and comedy rolled into one, dialogue blended with naach-gaana, and so on. They hate walls — they want to break down the partitions that divide us, as we can see in films like Parineeta or Deewar (whose hit song is ‘Todenge Deewar Hum’). But there is another ingredient that seems crucial to me: In a masala movie, the language itself is a mixture. The worst-kept secret about the ‘Hindi’ masala movie is that it isn’t always in Hindi. It moves most obviously between Hindi and Urdu, with occasional detours into Punjabi and Bhojpuri and Marathi and English. And that’s why a good masala film is, at its heart, deeply inclusive. I think of a film like Amar Akbar Anthony. Not only does it present the sublimely nutty story of three brothers from three different religious communities separated at birth and reunited later in life; its dialogues swerve across languages, as do its song lyrics (“My name is Anthony Gonsalves — main duniya mein akela hoon!”). Rajnikanth’s latest Tamil blockbuster, Petta, also seems to me a particularly good, if increasingly rare, example of a masala film. Its story — about Christian and Muslim schoolboys who were once enemies coming together, under the mentorship of their Hindu hostel warden, to fight a UP-based Hindutva goonda opposed to cross-communal romance — strikes me as being the south’s ultimate masala revenge against the increasingly shuddhta-craving north. According to you, who are the movie makers of note in this genre? I am reluctant to single out individuals, because for me what is most striking about masala as a genre is that it can never be the expression of an individual. It is, rather, the expression of collectivities: the production team, the huge cast, the mass audience. That said, some directors and banners have been particularly striking in this regard. I have already mentioned Manmohan Desai; but I am a big fan of Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar’s scripts for films by Nasir Hussain (Yaadon ki Baarat) and Ramesh Sippy (Sholay). The last committedly Hindi masala filmmaker standing seems to be Rohit Shetty. Any memorable movie scenes that are quintessential examples of the genre for you? For me the most memorable moments of masala movies are always their item numbers — song and dance routines that distill the essence not just of the film’s story but also its larger, inclusive vision. ‘Kashmir Main, Tu Kanyakumari’ in Chennai Express is a good recent example. I love the item number ‘Jhalla Wallah’ in Ishaqzaade too. What might seem initially like a sexist sequence featuring a scantily clad naach-girl transforms, as you listen to Kausar Munir’s brilliant lyrics, into the most beautiful, creative celebration of love and language’s movement across boundaries of language and community. That song, like the film’s lead characters, like the film’s audience, is a wonderful mix of Hindi and Urdu, Hindu and Muslim, and is not reducible to either. Do you like masala cinema? Well, duh — obviously! I am a tip-top, fully-formed, 100 percent number one masala-bhakt. [caption id=“attachment_6102751” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  The cover of Masala Shakespeare, by Jonathan Gil Harris[/caption] What do you dislike about masala cinema, if anything? It doesn’t have a particularly distinguished tradition of progressive gender politics. And its inclusivity doesn’t usually extend to caste, though there are occasional, if flawed, exceptions such as Kachhra, the Dalit spin bowler in Lagaan. Is Indian cinema moving away from this genre? Yes. Since liberalisation, masala has been slowly dying. Indian tastes are becoming more influenced by Western movies, and production companies are catering to that. Most importantly, we have seen the more or less complete death of the single-screen cinema hall. Films are almost exclusively made for screening in multiplexes or view-on-demand platforms such as Netflix. As a result, watching a movie with a huge mixed audience is now an experience that most film-goers under the age of 25 haven’t had. What are the elements of masala cinema that are vanishing? Are there elements that continue to linger on? The element that is most obviously vanishing is naach-gaana. I wouldn’t want to be a Bollywood choreographer these days, there’s less and less work for them. Karan Johar has announced that he will no longer have item numbers in his films, because he thinks they are sexist. But if we think of item numbers simply as vehicles for the male gaze to feast on the sight of dancing female bodies, then we miss the point they have served in masala films. They aren’t simply eye candy. They do a lot of other work too. A good item number brings outstanding lyrics, often in Urdu, into conversation with the larger movie. Just think of what Gulzar’s ‘Chhaiyya Chhaiyya’ does for Dil Se, beyond introducing us to Malaika Arora Khan on top of a train. “Woh yaar hai jo khushboo ki tarah, woh jiski zubaan urdu ki tarah” — that’s the theme of the film in a nutshell, of opening ourselves up to the ‘other’ as if it were a fragrance, as if it were Urdu itself. The film asks us to think outside the confines of our community or clan. But I wouldn’t want to suggest the sequence is simply about the lyrics rather than the visuals. The item number is meant to be repeatable by the audience, who will not only sing it but also imitate its dance moves at home, on the streets, even on train tops. It is an invitation to collective activity. That is so different from what a song does in a Hindi movie made for the multiplex or for Netflix. Songs are still vital parts of Hindi movies, but increasingly as background soundtracks or closing credit sequences. They are not invitations to think or to act collectively. They are invitations to download onto one’s private hard drive. There are some exceptions, like Sanjay Leela Bhansali and Vishal Bhardwaj, whose films offer amazingly interesting naach-gaana sequences. It’s no coincidence that both men are musicians. Why is Indian cinema moving away from masala? What are the artistic underpinnings of this development? I don’t see the underpinnings as artistic but as economic, social and political; the ‘artistic’ justifications for the move away from masala are shaped by those factors. Does the vanishing of masala cinema have anything to do with the current political climate? It’s no coincidence that the blockbuster masala movie, at least in Bollywood, has pretty much died in the last five years. There have been a few exceptions, but I can count them on the fingers of one hand and nearly all involve the Khans, who come from an earlier age. We are living in a time when the zealots of shuddhta and communalism are speaking in very, very loud voices. Films that champion inclusivity and mixture, that see India as a conversation between many cultural traditions rather than as a Hindu rashtra, are less appetising to bankroll. And on the rare occasions that filmmakers do ask us to think about the oppression of minority communities, as was the case with Mulk, they tend not to resort to masala as a genre — they prefer a kind of adapted version of the Hollywood ‘social topic of the week’ drama. You say that masala cinema refers to a certain idea of India. Could you elaborate? Masala cinema celebrates multiplicity — the more-than-me, the more-than-my-clan, the more-than-one. For a long time, the dominant idea of India was of its more-than-oneness, its often messy yet extraordinarily rich plurality. And masala movies were the cinematic corollary of this idea. This masala ethos is rather different from the rainbow ideal of plurality one finds in the West, where each cultural colour has its own integrity and doesn’t mix with the others. Masala is altogether messier, because the ingredients all become part of each other. In Hollywood, Amar, Akbar and Anthony would be three American immigrants from three different countries. In Bollywood, they are literally brothers; they are inextricable from each other. And that makes for a much messier state of affairs at a time when the new idea of India is all about uniformity rather than unity. We’ve become impatient with messiness; we want Swachh Bharat Abhiyan. It’s a dangerous wish. Bharat cleansing and ethnic cleansing, as we are seeing, are frighteningly close.

Author Jonathan Gil Harris on how masala films are a syncretic mix of traditions, what the significance of item songs is, and why the disappearance of single screen theatres has sounded a death knell for the genre

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)