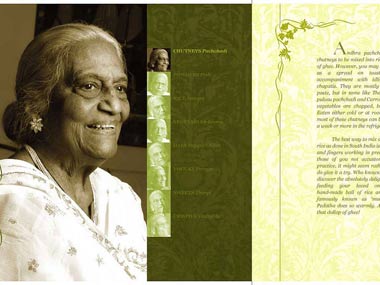

My first book assignment was an easy one. It was no great work that would demand hours of creative toil. Or so I thought. The job on hand was to compile a treasure house of my mother’s little-known, typically Iyengar recipes. Having always dreamt of seeing my name on a book cover some day, I agreed with alacrity. And I felt a secret thrill: perhaps now my friends would realise that South Indian food stretched beyond idli and sambar. Three months down the line, I was a mess. My brow was furrowed, as if I had spent time in a kitchen with no fan, toiling over that old-fashioned stone grinder my mother used in her younger days. [caption id=“attachment_146353” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=“Representative image. Cover of Cooking at Home with Pedhatha published by Pritya Books. PrityaBooks via Flickr”]  [/caption] The recipes themselves were just fine. They would each produce aromatic tastebusters if put to the test – by my mother. The problem lay in translating her expertise into knowledge that could be shared with the uninitiated — in converting a legacy of ‘pinches of this’ and ‘a handful of that’, a ’little of this’ and ‘some of that’ into cups, teaspoons, and kilos. Having been a food editor in the past, I knew that cookbook recipes require an order and a method, that the ingredient used in the largest measure goes first on the list, followed by the rest in descending order. The method of preparation too has to be perfectly linear. We, however, are a nation of chefs who cook by instinct, tutored not by cookbooks but at the side of our mother, grandmother, aunt or mother-in-law. The creation of each dish is a spontaneous act, like a poem written in a moment of inspiration. There is little guarantee that a dish will taste exactly the same every time. There is no recipe to consult, no measurements to weigh out laboriously. It comes by habit and instinct, the mix and match of a yummy recipe. (It is, of course, the undoing of every young bride whose man wishes his sambar or rajma to taste exactly as that of his mother, but that’s another story.) More importantly, the traditional Indian cooks blind. If she does forget by some catastrophic mishap to put in salt in the rasam, she will never know — and will have to bear the embarrassment of having it pointed out at the table. In a traditional kitchen, an Indian woman does not taste the food as she cooks. Food prepared in Indian homes is an offering to the gods; the food is theirs to taste before mortals can partake. Then there is the concept of jhutha, the idea that once-tasted food is unclean and cannot be offered to others. This is the test of a great Indian cook: to be able to make a great dish, usual or unusual, without tasting it once. No room then for finetuning, for dumping that panful of sauce because it is not quite right… the test of the pudding, as they say, is really in the eating! Given my love for all things culinary, my latest obsession is MasterChef Australia. I love it all: the easy camaraderie and intense passion of the contestants, the twists and turns, the sheer excitement of hunting for secret recipes across New York City, the mystery ingredients: sea urchin, pigs legs, hmm… The imagination boggles even as my taste buds hide in horror. Yet hooked on to competitive cooking shows like MasterChef Australia (or India), we forget the multitude of Indian mothers, daughters and wives who face far more rigorous tests each day — in their own kitchens. What if, for example, MasterChef Australia went truly native? Would this impressive lineup of chefs flounder without their trusty recipes or the gleaming array of measuring cups and spoons? It might indeed be an idea that can take wings and fly Down Under to challenge the chefs who wear their Michelin stars with such pride. Given that the most seasoned among them lose out to rank amateurs when denied the printed recipe as reference, this twist to the tale might be the ultimate teaser, the irresistible mystery ingredient that sends TRPs flying into the stratosphere. Finally, a truly Indian masterchef to challenge the world!

Forget all the brouhaha over MasterChef Australia. Indian cooks face far more rigorous tests each day in their own kitchen. Tests that most Michelin starred chefs are likely fail.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)