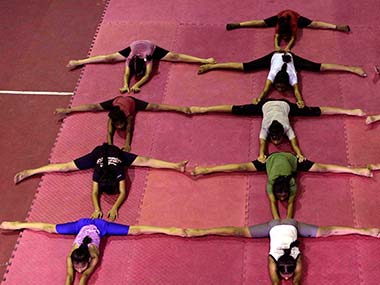

Disclaimers are normally posted at the end of a piece. This time, however, I feel it is safer to begin with one. I am not a parent. I am a loved and loving aunt to a bunch of nieces and nephews but that is like comparing diet cola to the real fizzy thing. I am a mere bystander to the parenting process, watching from the sidelines. As such, I am often in awe of parents, especially the mother. Their commitment to their children is intense and unabated. Note to Joss Whedon: Mommy 2013 would make a fabulous addition to The Avengers should the Hulk ever drop out. Seriously, though, all the admiration aside, this extreme investment in their offspring is proving to be a double-edged sword. While it gives children more direction and equips them with tools for success, it fails to give them room to experiment and even fail. The really scary part – this single-mindedness about the child’s success has spilled over to all aspects of his or her life. Indian parents have always been overly competitive and demanding about their children’s academic performance. We know that. But the pressure used to come off outside the classroom. For instance, back in ’80s and early ’90s, there was this thing called a ‘hobby’. You may have heard of it. They comprised activities that children took on for pleasure and left when they got bored or found something they enjoyed more. It could be a musical instrument or a sport or even stamp-collecting. [caption id=“attachment_710536” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  Representational Image. Reuters[/caption] An extreme example of this was someone like me. I was probably an outlier but I remember trying out every musical instrument possible, joining various art and dance classes, collecting stamps and coins by turn and even planting vegetables for a lark. ‘For a lark’ – a phrase very few children belonging to the new-age, reasonably affluent, educated parent would even be aware of today. My mother would get irritated at my lack of focus but that was more from a practical, financial point of view. Her anger was directed towards the wastage of time and money rather than her daughter’s failure to become the ‘best’ at what she does. Sometimes I wonder if I might have become a great pianist had she insisted on waiting for me outside the class, quizzing me about what I learned that day and discussing my flaws and strengths with my teacher on a regular basis. And then I stop wondering because the pressure of expectations to excel in what was supposed to be a time-out from the drudgery of academics is unacceptable. And unnecessary. When did play and work become the same thing? This question began as a random observation which I shared with friends and family but the more I discussed my views, the more ratification I found, even from parents admitting to their own inability to give their child room to stumble, fall and then pick themselves up. I recently found this study mentioned in The Atlantic in an article title Why Parents Need To Let Their Children Fail that corroborated, to some extent, my sense of where we are headed. The study describes the phenomenon as “overparenting” where the child isn’t given the chance to resolve his or her own issues. Their needs are swiftly taken care of and the path to success is smoothened, yet again. My premise has been that by ensuring our children always succeed, we are somehow setting them up for failure. You need to allow them to do things on their own, yes. But I would like to add this: They should also be allowed to do things they may not be good at. That experience is as important as it is to know the winning feeling. Take this eight-year-old boy who wanted to join an art class but was forbidden to do so by his mother because she would rather he focused on football. The time freed up from the futile painting fetish could be used for more useful pursuits. In another case, just because this seven-year-old girl is creative and artistic, her parents are already drilling into her head the prospect of design school in New York. I don’t know if you watch One Tree Hill, an American teen drama which ran in the US in the 2000s, that has recently started airing on Indian television again. Scratch the surface of the usual teen angst that the show necessarily contains and you find some interesting parenting insights. One of the two protagonists of the series, Nathan Scott, is a basketball player much like his father. But since Scott Senior wasn’t able to take his own talent to the big league, he is shown as obsessive about his son’s career. Their entire relationship is centred on the sport with the father pushing the son so far over the edge with the burden of his expectations that Nathan drops out of the team altogether. It isn’t that he doesn’t love the game but his father’s bullying – and there is no other word for it – made him learn to hate it. This comment may seem to be a harsh judgment on parents. And it certainly appears to be a sweeping statement on all. But it isn’t. Parenting is a grey area. It is also the toughest job in the world. No parent intentionally sets out to ‘bully’ their own children. They always want the best for them but too many factors have compelled them to also want their children to be the best. Consider, for one, the sharp increase in difficulty levels for college admissions. “The percentage cut-offs for top Indian colleges are ridiculous, so we have to think about sending them overseas,” said one mother. And the CV value of doing well in a sport or any other extra-curricular activity cannot be overstated. Then I was told the cost of putting them through a sport or any other pursuit. “There are different shoes for different sports, did you know that? Badminton has one version, tennis another and football yet another,” another parent pointed out. Even though the demographic of parents I spoke to wasn’t short of funds, the points they made didn’t lack sense either. “If each sport costs me thousands per month, why should I not want my child to do well in it? And what kind of message am I sending him if I allow him to jump from one sport to another at a whim?” a father said to me. Like I said, this isn’t the ’80s or even the ’90s. And I get it. But every now and then, even well-intentioned parents need to slow down and look in the mirror and see if they aren’t letting the pace of the world chase their child’s playful innocence away too quickly. They may be little but they absorb the sense of expectation faster than we think. My friend’s nine-year-old boy asked her today if he was ever going to make it to a real team. This was after he had played some top-notch football to help take his school team to the semifinals. His mother’s voice was tinged with sadness at her child’s anguish. It’s too soon for such disappointment. The hardship of being a parent, especially a mother, isn’t lost even on me. Thankfully, for them, there are several help-groups and communities that have sprung up online showing that they are not alone. One such, called First Moms’ Club, is currently a Facebook group comprising 1,500 mothers that seek comfort in each other’s tales. The knowledge that another mother has grappled with similar issues and perhaps dealt with it in a non-conventional, non-aggressive manner can be a way to turn the tide back in the direction of normalcy and childhood again. All this being said and done, there is another little tip that a new study offers the Indian parent. Don’t worry, it isn’t preachy. In fact, it has the potential for some fun learning. The article, again in The Atlantic, titled How Parents Around The World Describe Their Children, In Charts, indicates that American parents tend to describe their kid as ‘intelligent’ while their European counterparts talk more about happiness, ease of handling and even-temperedness. It doesn’t require a nationwide survey to figure out which side of the globe Indian parents tend towards. American aggression and competitiveness has always been attractive and aspirational to us. But diluting that with a dash of European laidbackness may be just the tonic that not only our children need, but also their beleaguered, demonised parents. The author writes on popular culture, cricket and whatever else takes her fancy.

Sure, we have pushy moms who want their kids to excel in studies. But playtime? Is it now more about play, or one more competitive rat-race?

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)