Eighty-three year old Meena Talwar recalls her time as a 15-year-old college student at Delhi University’s Miranda House in 1952. Passionate about cricket, she played for the Roshanara Club, one of the earliest cricket clubs in Delhi, and was called “Demon Meena” by the Women’s Cricket team of the British High Commission in India for her excellent bowling. Once she started taking wickets, she could not be stopped. While the college’s institutional history can be traced through official and bureaucratic records, and has been well-documented on their website , it is such individual histories that Dr Shweta Sachdeva Jha, Assistant Professor at the college’s English department, has set out to collect through the Miranda House Archiving Project (MHAP).

The idea sparked when she was looking for older issues of the college magazine. Instead, in an old trunk in the attic, she came upon photographs and documents from early decades of the college, which was founded in 1948. The photos piqued her interest in understanding what these women felt, and how they experienced the college space. “[Institutional] history needs to be understood from the point of view of college students,” she says. “The idea is to document what young women felt like when they went to college in the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s.” For instance, “I don’t want to know more about Sheila Dikshit the politician. I would have loved to know Sheila Dikshit the student,” points out Jha. What did she feel like as a student? What were the things that were happening around her, and how was she responding? How was she feeling about the politics of the time? With MHAP, it is such personal, intimate histories that Jha has set out to collect. [caption id=“attachment_8959661” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

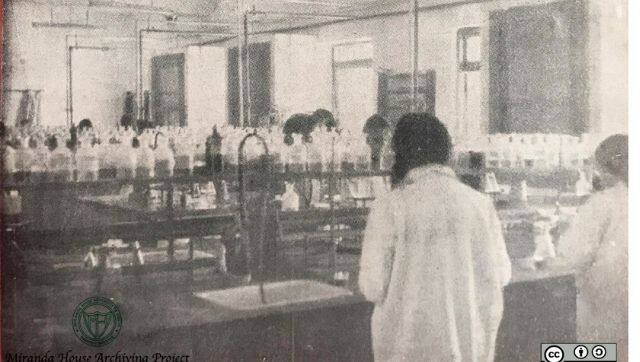

A laboratory in the science lab[/caption] While oral histories rely on memory and are never entirely objective, such people-oriented stories offer insight that one would not normally find in traditional archives. For instance, by asking alumni about how they got to college and the challenges of public transport, one can understand if and how much the hardships women face today have changed, and how much we, as a society, have moved forward. “To me, it’s very important because the university space is changing very fast. [It’s also] going through a lot of changes in terms of politics and solidarity. It’s important for us to figure out where we are right now. And I think young people, especially women, should know where we come from,” says Jha. Besides giving a voice to individuals, and providing an alternate history of the institution, such anecdotal histories are also highly relatable. This is especially important since the university has become more diverse over the years, with women from different backgrounds and from various parts of the country coming to Miranda House. And through following these stories, common threads start to emerge, allowing for connection. “History can be very academic and jargon-oriented, but I think [such] stories are something that anybody can connect to,” says Jha about MHAP’s individual, experience-based histories. [caption id=“attachment_8959651” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

A laboratory in the science lab[/caption] While oral histories rely on memory and are never entirely objective, such people-oriented stories offer insight that one would not normally find in traditional archives. For instance, by asking alumni about how they got to college and the challenges of public transport, one can understand if and how much the hardships women face today have changed, and how much we, as a society, have moved forward. “To me, it’s very important because the university space is changing very fast. [It’s also] going through a lot of changes in terms of politics and solidarity. It’s important for us to figure out where we are right now. And I think young people, especially women, should know where we come from,” says Jha. Besides giving a voice to individuals, and providing an alternate history of the institution, such anecdotal histories are also highly relatable. This is especially important since the university has become more diverse over the years, with women from different backgrounds and from various parts of the country coming to Miranda House. And through following these stories, common threads start to emerge, allowing for connection. “History can be very academic and jargon-oriented, but I think [such] stories are something that anybody can connect to,” says Jha about MHAP’s individual, experience-based histories. [caption id=“attachment_8959651” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

A laboratory in the science lab[/caption] In her efforts, Jha is supported by three former students — Gayatri Punj, Devika Gupta, and Shailee Rajak, along with non-teaching staff Pawan Kumar, and the Amba Wadia Fellowship by the SNDT Women’s University, which encourages the documentation of different aspects of women’s history. Their work includes connecting with the alumni network, scanning the photos they have found and identifying and tracking down the women populating them, and sending out a call for submissions. Although they share stories on social media, the eventual goal is to set up a website where these photos and their stories can be recorded and made easily accessible, while also finding a way of preserving the photos they have found. [caption id=“attachment_8959641” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

A laboratory in the science lab[/caption] In her efforts, Jha is supported by three former students — Gayatri Punj, Devika Gupta, and Shailee Rajak, along with non-teaching staff Pawan Kumar, and the Amba Wadia Fellowship by the SNDT Women’s University, which encourages the documentation of different aspects of women’s history. Their work includes connecting with the alumni network, scanning the photos they have found and identifying and tracking down the women populating them, and sending out a call for submissions. Although they share stories on social media, the eventual goal is to set up a website where these photos and their stories can be recorded and made easily accessible, while also finding a way of preserving the photos they have found. [caption id=“attachment_8959641” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

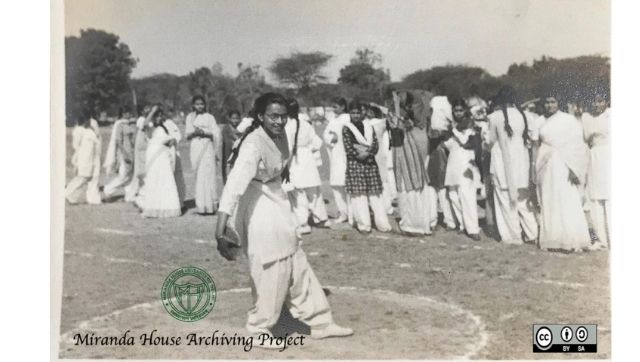

Sports day, 1952[/caption] In the team’s interviews with alumni, they follow the same procedure that is in place for collecting oral histories, sharing consent forms with participants and collecting submissions. The COVID-19 lockdown has rendered direct interviews almost impossible. “A typical oral history interview would have been more fruitful as it allows us and them to participate and recollect their experiences in a more intimate and warm manner,” says Jha about the direct method, which can also lead to more spontaneous revelations. Instead, they are engaging with interviewees online, who are often helped by their families. In one case, with an alumnus of the first batch who graduated in 1951, an online interview was not possible either. The MHAP team reached out to her daughters with a set of questions, who will record their conversations as audio notes for the archive. “This is collective history at its best, and very heart-warming,” says Jha. Featured image: Sports Day, 1954, when the Chief Commissioner gave away the prizes * — All photos courtesy the Miranda House Archiving Project

Sports day, 1952[/caption] In the team’s interviews with alumni, they follow the same procedure that is in place for collecting oral histories, sharing consent forms with participants and collecting submissions. The COVID-19 lockdown has rendered direct interviews almost impossible. “A typical oral history interview would have been more fruitful as it allows us and them to participate and recollect their experiences in a more intimate and warm manner,” says Jha about the direct method, which can also lead to more spontaneous revelations. Instead, they are engaging with interviewees online, who are often helped by their families. In one case, with an alumnus of the first batch who graduated in 1951, an online interview was not possible either. The MHAP team reached out to her daughters with a set of questions, who will record their conversations as audio notes for the archive. “This is collective history at its best, and very heart-warming,” says Jha. Featured image: Sports Day, 1954, when the Chief Commissioner gave away the prizes * — All photos courtesy the Miranda House Archiving Project

)