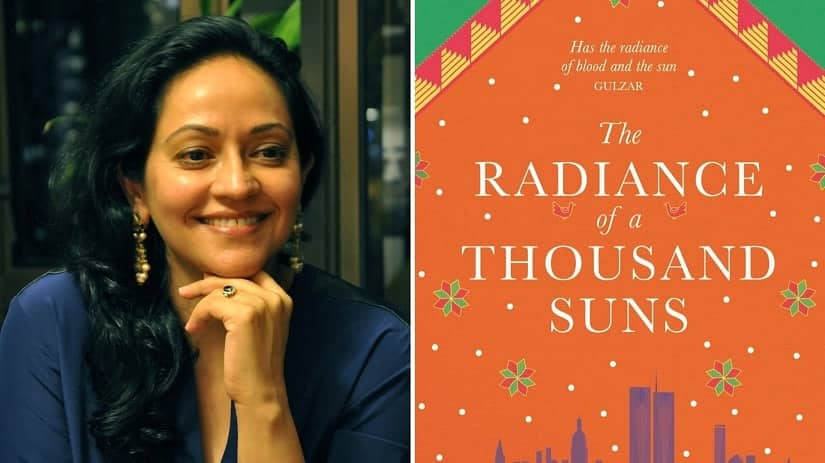

Like the massacre it deftly documents, Manreet Sodhi Someshwar’s The Radiance of a Thousand Suns is an inter-generational affair with continuing implications. In this exploration of the 1984 anti-Sikh violence, grief recedes from being all-encompassing to a solitary moment in a drawing room. The book begins in the pastoral lands of rural Punjab and ends in sync with the frenetic cadence of New York City, its characters learning to let go with each chapter. On the 35th anniversary of the carnage that changed India forever, Someshwar spoke with Firstpost about what inspired The Radiance of a Thousand Suns, the women of the narrative, and why the story is theirs to tell. Edited excerpts below: When did it dawn on you that you must write a book on the 1984 riots? Writing snuck upon me in the guise of a tai tai, a Chinese colloquial term for a woman of leisure. I was to take a sabbatical from the corporate life in Singapore. On my way to realising this barmy prospect, I collided with the plains of Punjab. Rather, its fields. That grew mustard and wheat and rice and, for a period in the eighties, militants. Which made my little town on the Indo-Pak border a militant hotbed. And images started to swim up, of a time that I had left behind, or so I thought…I tried to resist, but one memory led to another, then a labyrinth opening up for me to wade in. [caption id=“attachment_7569721” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  File image of Manreet Sodhi Someshwar; cover for The Radiance of a Thousand Suns.[/caption] To make sense of those memories, I started asking questions. The writing of the book was another labour altogether as never having studied Literature or Creative Writing, I had to teach myself to write. Seven years later, I finally had my book: The Long Walk Home, which is the first fictional examination of the turbulent 20th century history of Punjab. How long have you nursed the idea that became The Radiance of a Thousand Suns, and how challenging was it to see it to fruition? For 20 long years! A desire to understand and explore the pogrom of 1984, was my entry into writing. However, I felt I had not been able to do justice to it in The Long Walk Home. In hindsight, I realise I wasn’t skilled enough yet to write the book that is now The Radiance of a Thousand Suns. I needed to grow as a writer, mature as a woman, develop my perspective in order to bring to text what I had in my mind. The anti-Sikh violence of 1984 couldn’t be written in isolation — there was an entire history, and mythology, which undergirded that cataclysm. Additionally, I wanted it to be a narrative of, and by, women. But women exist only as data in documentation and books on Partition and ’84. So I had to seek out women’s stories via oral testimonies to hear what they had been saying all along but which nobody was hearing. For instance, in their witness testimonies to the commissions set up in the wake of 1984, since women used the euphemism of “dishonour” and “humiliation”, the crimes of rapes were not registered or accounted for. Trauma is pervasive in your books, especially in the lives of its women — Nooran, Biji, Niki, and Jyot. Were there tropes you consciously avoided or embraced while depicting their pain? In the telling of any story, it is also important how we tell the story. I structured my novel such that it reflects the theme of trauma, the past forever intruding upon the present. It was deliberate since we as a people have not been able to live down the orchestrated violence of 1947, which replayed in almost identical fashion in 1984, 1991, 2002. Women bore the brunt of this violence. However, the depiction of violence against women has been commodified to an extent where it is a trope in itself. And yet, the reality is that women’s stories are stories of extraordinary courage in the face of violence, in the impossible choices they are forced to make to keep their loved ones safe, to keep living when so much has been snatched from them, in the camaraderie they share with other women, in the stories they tell to share their secrets… It was clear to me that this narrative would be women’s to tell. Why did you see a link between the chapters of the book with certain episodes of the Mahabharata? I knew that Radiance would be built on a scaffolding of the Mahabharata. It is our foundational epic, one that also gave us Draupadi, who is a leitmotif in the novel (along with Heer, that feisty woman of Punjabi folklore.) In order to grapple with the present, sometimes, we have to engage with the past — a close scrutiny of tradition, an exploration of homilies so we can parse the narrative for our stories and question the status quo. We must ask ourselves why, after over 70 years of Partition, have we not been able to lay the ghosts to rest? In 1947, when women’s bodies became the battlefield, did that template of sexual violence derive from our foundational epic? Does the fact that women bore the brunt of that violence echo in this time of #MeToo? I worked in the parallels as I wrote, sharpening them with subsequent drafts. As Vyasa says, “What is not in the Mahabharata is nowhere else.” How does a writer get through the ‘death’ of characters with immense promise — Jinder and Nooran in your case? Whilst writing the first draft, which was an organic process since I wanted the characters to lead the story, I recall I went to a live concert. The manuscript was in its early stages and I was tremendously excited with how Nooran was shaping up. And then, abruptly, my stomach hollowed because I realised that for Niki to grow fully into the person who would fulfil her father’s legacy, I would have to cut her umbilical chord with Nooran. The thought devastated me. I will circle around that scene forever, keep delaying having to write it, until I absolutely must. Fiction mirrors life.

On the 35th anniversary of the carnage that changed India forever, Manreet Sodhi Someshwar spoke with Firstpost about her book based on the 1984 anti-Sikh riots, The Radiance of a Thousand Suns, the women of the narrative, and why the story is theirs to tell.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)