A 2013 interview by The Guardian mentions that writer Lucy Ellmann “has been described as ‘one of modern literature’s most well-kept secrets’”. In 2019, her eighth book, Ducks, Newburyport, has made it to the Man Booker Prize shortlist , alongside Salman Rushdie, Elif Shafak, Margaret Atwood, Bernardine Evaristo, and Chigozi Obioma. The American-born British novelist, however, is no stranger to accolades. Her debut novel, Sweet Desserts (1988) came at a time when she wrote on art for the Times Literary Supplement; the book explored the convoluted lives of two sisters with an Oxford art historian father. It went on to win the Guardian Fiction Prize the same year. In her latest literary outing, Ellmann tells the story of a middle-aged woman who is a mother of four and a survivor of the “most embarrassing kind of Cancer” from Ohio.

Devoid of paragraph breaks, Ducks, Newburyport, unleashes the serpentine, perambulating thoughts of Ellmann’s nameless narrator in towering blocks of words — made of a single sentence.

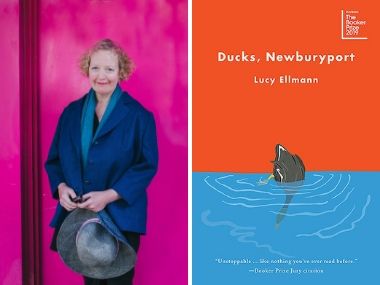

Sample this excerpt: …[T]he fact that I don’t like licorice, I just like the way Good & Plenty look, though sometimes they look like microbes_, if you’re not careful, which is none too appetizing, gosh, Goshen, New Philadelphia, the fact that the stink that came out of that chicken place was a scandal long before the tornadoes, chickens by the trillion, the fact that the whole idea of keeping animals in such numbers is disgusting, disgusting, the fact that there’s something really sick about it, one hundred and ten billion chickens, zillion, trillion, trillium, Goldfinger, the goose that laid the golden egg, the fact that trillium’s the state flower, frillium, brillium, fritillaries,_ ‘twas brillig and the slithy toves_, trivium, trivia, the fact that Ohio is like a trillium petal hanging off Lake Erie,…_ The narrator’s mind veers from the mundane to the frightening, from chicken and eggs, to Trump’s politics of racist horrors — which she’s relieved that her parents aren’t around to witness — all within the span of a solitary sentence. While it spans a formidable 1,000 pages, Ellman’s Booker-nominated story of an Everywoman in the 21st century reflects on an eerily familiar world that’s already hit the self-destruct button. In an interview with Firstpost, Lucy Ellmann talks about the success of her latest book, her connection with James Joyce, and why she prefers Anne Elliot’s story over Elizabeth Bennet’s. [caption id=“attachment_7331361” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Lucy Ellmann, author of Ducks, Newburyport, which has been shortlisted for the Booker Prize, 2019.[/caption] Ducks, Newburyport is a 1,020 page-long novel, which is essentially a nameless narrator’s train of thought, or what I felt was a lucid jumble of associated ideas. Did you expect the book to get such a positive response, considering it’s so experimental in nature? (Your regular publisher, Bloomsbury, passed it up — it was later picked up by a small, independent press…) Galley Beggar Press is extraordinary. They work on a shoestring, but their taste in writing is so bold, so artistic. They bravely took on this massive book, which was very expensive to produce, and they made a huge success of it. My admiration and gratitude are boundless. But I don’t consider my novels ’experimental’. They are simply an attempt to say what I want to say. Each inevitably demands a different form. There’s no point in writing the same book twice! The word ’experimental’ makes the whole enterprise sound so dubious and tentative, so doomed to failure.

I don’t consider originality such an outlandish aim for a novelist.

Did I expect this sort of reception for Ducks? I really had no idea what people would think of it. It’s been thrilling to find out. I still don’t really know though what it’s like to read it, only what it was like to write it. (Exhausting!) You just have to write something you believe in, and hope for the best. The restless mind of the narrator does not seem to have the luxury of dwelling on something for too long, like most people her age. She seems to treat the banal and the exciting equally, without assigning any hierarchies to her thoughts. Why did you think this technique would make for compelling storytelling? Thoughts don’t wait quietly in an orderly queue. The mind is an undemocratic unruly place. Over time though, recurrent thoughts do suggest what my narrator cares about most, maybe even what I care about – what you call ‘hierarchies’. But that is all up to the reader to decipher. I wouldn’t call the narrator’s mind inherently ‘restless’ either: she’s actually probably quite a calm person, if circumstances were right. But she’s surrounded by the horrors of American life, and these take their toll on her equanimity. Sorry to be so picky with this question, but I kind of object to the word ‘storytelling’ too. Are we children? The ‘story’ I tell in this novel is about the play of thoughts that jostle for attention in the mind. You seem to have a penchant for heroines who would conventionally be thought of as “past their prime”. In Ducks, Newburyport your central character is middle-aged. In Mimi (2013), the heroine was going through menopause… That doesn’t mean you’re not in your prime! I don’t agree that women become valueless once they reach 40. Quite the opposite, in fact.

Older women seem as neglected by fiction as they are by Western society as a whole. So many writers, even good ones, seem to believe that only young women are worthy of notice. But where’s the challenge in that? It’s all too easy to write about pretty young things, for whom the world constantly gushes its pressurising appreciation.

This is what makes Persuasion one of Jane Austen’s most touching books – Anne [Elliot] is past it. She’ll probably never be poor at least, but it looks like she will be alone and beholden all her life. That is actually much more interesting to me than Elizabeth Bennet’s rosy position. Eliza turns down marriage proposals like nobody’s business. Anne was forced, persuaded, to turn one proposal down years ago, and has lived to regret it with her whole being. Now, that’s a story! In my earlier books, I wrote about bodily functions but had nothing to say about the menopause, because I hadn’t personally been through it yet. After ten years of hot flushes, the case is rather different now! What infuriates me is silence around subjects like menstruation and the menopause. These things fill the lives of half the human population! Why are they never mentioned? They are shrouded in secrecy and embarrassment, which is a great way of keeping women down. Patriarchal societies learnt long ago to treat anything to do with the vagina or womb as shameful. But what’s really shameful is the unbelievable mess men have made of the world. [caption id=“attachment_7331371” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Cover of Ducks, Newburyport.[/caption] What, as a writer, do you crave to create at this stage in your career, now that you’ve been writing novels for more than half your life? Do you think your readers have changed, or evolved, over the years? To my surprise, many readers seem as impatient with crummy conventional fiction as I am. They’re hungry for something more strenuous, something that takes effort to write and to read. This book nearly killed me! But it seems to have been worth it. It’s been met with such a generous welcome. Are you attributing more guile to the writing process than there is? I don’t think writers plan out what they ought to write in the way you imply, nor worry about whom they’re writing for. I write for myself, and follow my nose. Nor can I assume my previous readers will still be there awaiting the next book, since it takes five or more years for me to write one. Ducks took seven. By the end of that, you feel about as far away from readers, or from humanity itself, as you can be! So it’s wonderful to find people are out there, good readers, ready and waiting. I’m in awe of their resilience. What do I crave to create? A second loo! People often boast about their writing huts but when you enquire further, there’s no loo. That is not a writing hut, that is a place to go in between loo visits. What writers need is a room with an adjoining loo, and preferably a little picnic basket with your lunch in it – so that bodily needs become as insignificant as possible, and you avoid breaks in concentration. Your father, Richard Ellmann, was James Joyce’s celebrated biographer, and Ducks, Newburyport is being compared to Ulysses, and the narrator to Molly Bloom, by so many readers and reviewers. There also seems to be a Finnegans Wake hangover in your novel, reminding one of the famous lines from the book: “My leaves have drifted from me. All. But one clings still.” How much influence has Joyce actually had on you as a novelist? I admire Joyce immensely. Ulysses really moved me when I first read it in my 20s. With help from my father, a handy guy to have around, Joyce changed my life, and my attitude to what literature could do. Other modernists have added to that sense of a magnificently flexible art form. But I haven’t actually read Joyce for years, and feel his influence on me is largely subterranean. To my shame, I’ve not read Finnegans Wake yet. (I’m glad you have.) I now feel ready for it though. It took me years to work my way to it. Which writers, or books, have been your biggest literary influences? [François] Rabelais, [William] Shakespeare, [Laurence] Sterne, [Jane] Austen, [Charles] Dickens, [Thomas] Bernhard, [Elfriede] Jelinek – and Jean de Brunhoff (Babar).

What right have we to decide the fate of all living things? Patriarchy has deliberately obliterated our ability to think about the common good. The human race was capable of more than this. So I’m an advocate of matriarchy too: it’s the only way to travel.

Recommend a book to our readers, and tell us why we should read it. Leila Aboulela’s work is always extraordinary. In some novels, she has examined the position of the foreign and devout within British society. In Lyrics Alley, set mainly in Egypt, she created a rich world, Dickensian in scope, ranging from the torments of a paralysed poet to the practice of female genital mutilation (FGM). But her latest work, Bird Summons, is her wildest excursion yet. It jumps effortlessly from the mundane into the sublime, through myth and hallucinations, and is incredibly profound. Anyone interested in the best contemporary writing in English should read Aboulela’s work.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)