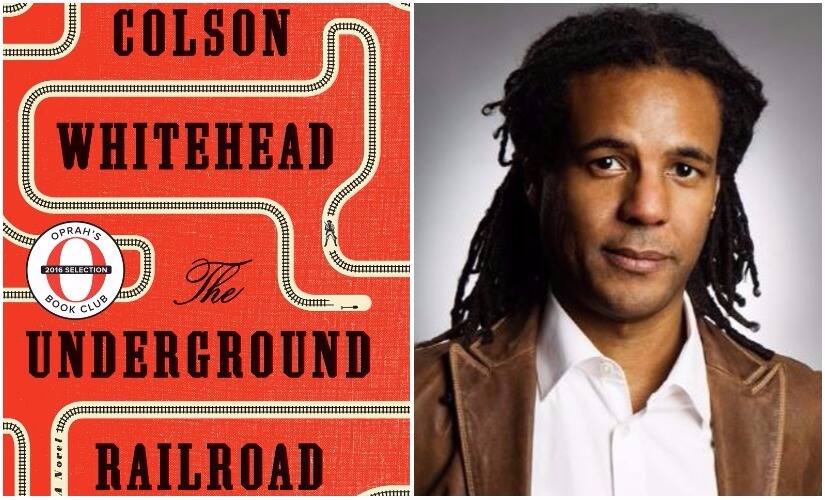

Editor’s note: Up to 13 September, when the Man Booker Prize 2017 shortlist will be announced, Firstpost will be reviewing all 13 books on the longlist. This is your guide to the Booker contenders, and which ones you should read. The title is literal. That’s the first stroke of brilliance. But Colson Whitehead has always been good at titles: A few years ago, when he wrote a memoir about the time he spent in Las Vegas taking part in the World Series of Poker, he called it The Noble Hustle: Poker, Beef Jerky, and Death (who doesn’t want to read about beef jerky?). He’s also good with opening lines: His first novel The Intuitionist, way back in 1999, was set in an elevator inspection service and opened with the almost-sadistic, “It’s a new elevator, freshly pressed to the rails, and it’s not built to fall this fast” (I can almost hear that as voiceover for the opening elevator scene from Speed). With his most recent novel though — The Underground Railroad — Whitehead is more subdued. The title, as I mentioned, refers to a literal underground railroad of trains and tunnels that startlingly juxtaposes on the historical metaphorical Underground Railroad — which was “a network of secret routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early-to-mid 19th century, and used by African-American slaves to escape into free states and Canada with the aid of abolitionists and allies who were sympathetic to their cause.” [caption id=“attachment_4001457” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad is on the Man Booker Prize 2017 long-list[/caption] The tunnels are built by mysterious hands, the trains and stations run by helpful station masters — both black (freemen) and white, and in the early-to-mid 19th century United States, this literal railroad is the one great source of possible freedom to the men and women enslaved across the country. Nobody knows too well where the trains go — deeper south and to misery, or to the free states and further north (Canada, where slavery was on the decline since the start of the 19th century and was fully abolished by 1834, was a refuge for many). But plenty are brave enough to get on the train. One such brave soul is our heroine Cora, and Whitehead’s first lines of the novel — “The first time Caesar approached Cora about running north, she said no. This was her grandmother talking.” — set the tone for an incredible and thrilling journey, quite literally, of one young woman in a time of almost-utter despair, as she traverses through half a dozen states and sees the “true face of America”. The Underground Railroad opens in the American deep south, on a cotton plantation in Georgia owned by the terrible and fearsome Randall brothers, who’re both like their father to varying degrees; in that they’re miserable and brutal white men who take immense pleasure in meting out all the imaginable and inconceivable types of torture that unfortunately defined slavery in the US. But this isn’t a story of the Randall brothers. This is a story of Cora, our teenage protagonist. A third-generation plantation slave, Cora is every bit her mother’s daughter and her grandmother’s granddaughter. Caesar, a northern slave who knows how to read, is willing to risk everything by making an escape attempt — he wants Cora to go with him because he considers her lucky. Why? We’ll soon find out. Almost immediately after Cora turns him down, we’re taken back to the life of Cora’s grandmother Ajarry — from her kidnapping in Africa to the unimaginable horrors she faces during her passage across the Atlantic, being bought and sold multiple times by numerous white folk, to the last place she ever sets foot on — the Randall plantation. Through failed suicide attempts on board to being treated as property, Ajarry marries three different men while on the plantation and bears five children with them. Only one survives — Mabel, Cora’s mother. In time, Ajarry dies a horrible death, on the Randall plantation: “As if it could have been anywhere else. Liberty was reserved for other people, for the citizens of the City of Pennsylvania bustling a thousand miles to the north. Since the night she was kidnapped she had been appraised and reappraised, each day waking upon the pan of a new scale. Know your value and you know your place in the order. To escape the boundary of the plantation was to escape the fundamental principles of your existence: impossible. It was her grandmother talking that Sunday evening when Caesar approached Cora about the underground railroad, and she said no. Three weeks later she said yes. This time it was her mother talking.” By the end of the first chapter, we know two things for certain: (1) Mabel escapes from the plantation, and (2) Cora is more like her mother than she’d like to believe. Cora’s relationship with her mother is one of the overarching themes of the novel. Ten years old when her mother takes off, without informing Cora of her plans, the hatred she displays towards the memory of her mother is understandable. Ironically, what makes Cora’s eventual escape attempt even more thrilling is her relationship to Mabel, not with her. Mabel’s eventual escape from the Randalls is not only a bone of contention for the plantation owners, but also a kick to the gut for the slave catcher whose desperate clutches she manages to elude — Ridgeway.

The Underground Railroad opens in the American deep south, on a cotton plantation in Georgia owned by the terrible and fearsome Randall brothers

Whitehead writes Ridgeway as a larger-than-life character (which, I suppose, is a prerequisite for a slave catcher) but also thoroughly vivid. He brought to my mind a mix of several famous characters from literature and television — something like a mix of Javert from Les Miserables and The Man in Black from Westworld. The descriptions of Ridgeway and his posse (which includes a white former gravedigger called Boseman who wears a necklace of ears that he won in a wrestling contest with a Native American called Strong, and a 10-year old black kid called Homer who voluntarily keeps himself with his former owner Ridgeway, rides their wagon, and maintains the “bookkeeping” of all things) are so evocative that you can almost hear the snarl in Ridgeway’s voice, the buzz of the flies that are drawn to Boseman’s prized necklace, or the indifference in Homer’s voice as he talks to Cora: _“_The driver of the wagon was an odd little imp. Ten years old…but imbued with the melancholy grace of an elderly house slave, the sum of practised gestures. He was fastidious about his fine black suit and stovepipe hat, extracting lint from the fabric and glaring at it as if it were a poison spider before flicking it. Homer rarely spoke apart from his hectoring of the horses. Of racial affinity or sympathy, he gave no indication. Cora…might as well have been invisible most of the time, smaller than lint.” Mabel’s escape haunts Ridgeway in a way that makes him double down on his search for Cora, and when he eventually does find her, Cora wonders if he knows that she hates her mother almost as much as Ridgeway does. Of course, the sad irony here is Mabel’s fate, as we find out towards the end of the book. The other major theme, of course, is the literal underground railroad. When Caesar first shows it to Cora, her surprise is obvious — but the more she gets to know of it and explore it, she realises that the railroad and the people associated with it, those who she loves and who help her, are her only chance at freedom. And she comes to respect it and savour it as one savours something that is rare and precious and sublime. This savouring is almost irritating — although we don’t read The Underground Railroad from Cora’s first-person narration, it clearly is her story. While she’s a quick learner, she steadfastly refuses to find more about the railroad. As a reader, my gripe with Whitehead and The Underground Railroad isn’t what many other readers seem to feel — that taking a revered figurative term and giving it a literal application belittled the actual underground railroad. On the contrary, I think it’s a genuinely sincere homage to the people who risked their lives and so much more, to be part of the underground railroad; however, I do wish Whitehead had elaborated more on this most fascinating mechanism. Every time Cora has an opportunity to actually ask someone about the railroad, when she’s in South Carolina or Indiana, she’s (relatively) happy. In that situation, she almost doesn’t want to disturb the status quo, which also explains why she’s often hesitant to leave. It’s understandable. But I feel like it was a narrative shortcut to leave such a gaping hole at the heart of the story. Whitehead manages to make up for that by indulging in several backstories — just like Ajarry’s quick background in the first chapter, we’re given small-but-useful-in-understanding-their-motives chapters for a few other characters — including Cora’s partner-in-escape Caesar. And Ethel, a god-fearing white woman who’s the reluctant wife of an abolitionist in North Carolina, who exhibits such a classic

white saviour complex it’s unnerving.

)