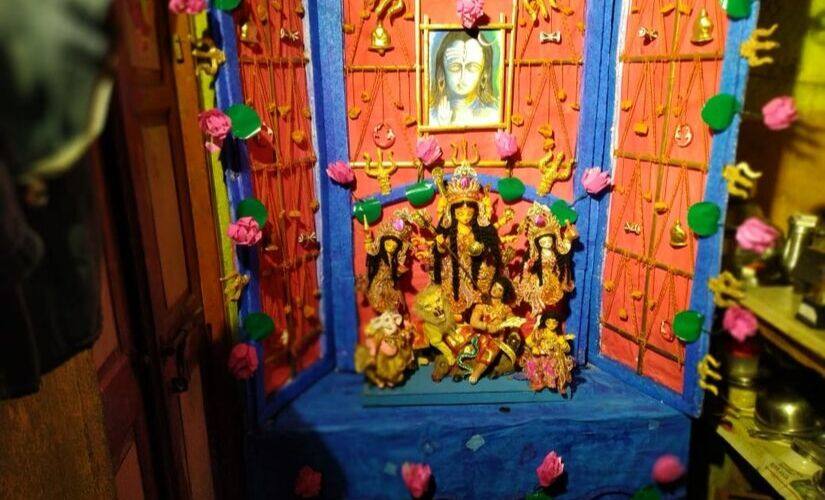

It’s that time of the year again, when the heady scent of the night jasmine fills the air and brings with it the festive spirit. For Pintu Majumdar, an artisan living in North Kolkata’s Kumortuli or potter’s quarter, it can only mean one thing — work, and more work. Only this time, there isn’t enough. “My family and I make jewellery and crowns for idols. I have been doing this for almost three decades, but have barely ever seen such abysmal business in years,” says Majumdar, one from among several generations of artisans settled in these narrow lanes in the old part of town. The annual week-long carnival of Durga Puja is undoubtedly the most anticipated event in Bengal, with several seasonal jobs generated yearly because of it. While smaller festivals comprise only a fraction of the workflow for the artisans making jewellery, most of them pin their hopes and rely heavily on this one time of the year for their livelihoods, as Durga is the most decorated of all gods. Organisations and individuals from across the world turn to Kumortuli’s trusted hands for their idols that are shipped globally. But the numbers have dropped drastically this year. “On an average, we do business for around 60-65 sets of such jewellery, which are made of paper, thermocol, beads, sequins, etc. This year, we’ve only sold 47 so far,” says Prasun Dey, owner of New Taraknath Stores. His father, Pradip Kumar Dey, founded the establishment over 30 years ago, following in the footsteps of his elder brother, who passed away recently. [caption id=“attachment_7341021” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Pintu Majumdar and Krishna Pal, artisans from Kolkata’s Kumortuli, make some of the last batches of jewellery ordered for this year’s Durga Puja[/caption] “It’s our family business, so some of our clients have been coming to us for decades now. The GST has gradually eaten into our business. Earlier, when a client would come to me and place an order for worth a lakh, he wouldn’t have to worry about bearing an additional cost of Rs 20,000, which now the GST imposes. But I am having to bear those extra costs while buying raw material, isn’t it?” Dey says. He goes on to elaborate on the crisis further. [caption id=“attachment_7341051” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  The jewellery is made of cardboard, thermocol, beads, sequins, all of which are put together either with glue, or by stitching[/caption] “There’s a family from Tripura, who’ve been coming to us for years now, since my father’s time. Even till last year they paid us 8,000 rupees for all the goods. This year, they said they can only afford to pay around five-and-a-half thousand. What do you do? They are old customers, you can’t turn them away, so you pay that difference from your pocket and shoulder losses. They may end up spending a lot on the idol, but once they come to us for the jewellery, they begin to bargain” he explains. [caption id=“attachment_7341061” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  A jewellery artisan at work in Kumortuli, days before Durga Puja[/caption] Dey’s shop employs eight artisans — including Pintu Majumdar — and all of them are from Kumortuli itself. Paying them on time is proving to be a challenge. “We did around 3.5 lakhs-worth of business last year during (Durga) Pujo. We obviously won’t reach those numbers this time,” he says, while putting the finishing touches on a four-foot-tall crown, being prepared for shipping to Bangladesh. [caption id=“attachment_7341071” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  A half-finished idol of Durga, waiting to be decked up[/caption] Their shop had crafted an 18-foot-tall crown two years back, tailor-made for a Durga idol owned by actor Prosenjit Chatterjee’s sister, Pallavi Chatterjee. No such projects have come their way this year. [caption id=“attachment_7341091” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Prasun Dey (left) and his employees at work in Kumortuli, as Durga Puja beckons[/caption] *** In the lane running adjacent to New Taraknath Stores is a narrow one-room establishment, where artists and their clay gods are elbowing each other for space. “Come in, Didi. Please watch your step. Those are the hands of Goddess Durga made by my sister Mala on the floor. She specialises in making hands for small gods,” says Gobindo Pal, aka Kalu. The orange warmth of a lone tungsten bulb lights up the walls that boast of several awards and certificates for his sister Mala Pal. Lined up underneath them are a dozen miniature idols of Goddess Durga with her children, in heights ranging from anywhere between a few inches to two-and-a-half and three feet. “Funnily enough, demand for small idols is incredibly high this time. It’s the first time that we are experiencing such a thing. The big idols aren’t doing that great, but smaller pujos seem to be picking pace,” informs Gobindo. He believes the reason behind this change points to the skyrocketing prices of goods, pushing people to celebrate on a smaller scale, with lesser money being spent on large idols, their clothing, jewellery, and transportation. In case of miniatures, the expenses are slashed down drastically. [caption id=“attachment_7448971” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Mala Pal at her workshop, modelling a miniature Goddess Durga out of clay[/caption] “These small ones cost anywhere between Rs 4,000 to Rs 12,000, or even Rs 21,000, as opposed to the lakhs spent on full-size idols. We even noticed how people celebrating at homes have become more keen on theme idols like they do in pandals,” Gobindo says. His sister has been in the profession since the age of 14. “This is a male-dominated business and my father would say that people object to a woman’s presence in this field. I would initially sit next to my brother and watch him work, and then I went to Delhi and enrolled in a handicraft course for a few months in 1986, a year after my father passed away,” she says. [caption id=“attachment_7448981” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  A miniature Durga[/caption] For the Pals, one of the handful of families making miniatures, and arguably the most renowned of the lot, business happens when Goddess Durga arrives. “The remaining year we do workshops and classes to get by. We are the only family in Kumortuli to teach and have students coming from different districts of Bengal. It’s only been five years that we’ve been doing this,” Gobindo says. A rival miniature business next door, also run by another Pal family, corroborates the fact that business for “chhoto (small) Durga” has picked up this year. [caption id=“attachment_7448991” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Mala Pal putting the finishes touches to a Ganesh idol.[/caption] But a few houses away, Fanibhushan Malakar’s Sheetala Stores isn’t in the mood for celebrations, much like other jewellery-makers in the neighbourhood. The 60-year-old establishment takes to manufacturing and selling topor (traditional Bengali groom’s headgear) and mukut (traditional headgear) for Odissi dancers during off-season, in order to earn an extra buck. However this year, the season is yet to bring good tidings. “Ganesh Pujo went big in Bengal this time, but its scale is nothing compared to Durga Pujo. The market is sinking for Durga this year, and I am afraid we might go bankrupt and die of starvation if our sales don’t pick up soon,” an artisan at the shop says, while sewing beads into a half-finished crown. [caption id=“attachment_7341141” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  At Sheetala Stores, artisans feel hopeless about the business done this season.[/caption] *** As we make our way out of the tarpaulin-clad neighbourhood of god-makers in Kolkata, rows of dhaakis welcome us back to the mundane, beating their cylindrical drums strung from their shoulders to the familiar, feet-tapping beats. The dhaak is typical to Durga Pujo, scoring the background for the festival that ushers in autumn in the eastern part of India. The congregation of dhaakis intensifies as one approaches the Sealdah Railway Station, where a barricaded enclosure in the parking lot has transformed into a musical carnival like no other. “We usually arrive a day or two before Pujo kicks off,” says Bamcharan Das from Birbhum, who’s taken the Rampurhat Express with almost 60 others from his village, to reach Kolkata. [caption id=“attachment_7449061” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Dhaakis unite at the Sealdah Railway Station in Kolkata[/caption] “We are farmers. During this time of the year, we play the dhaak to earn some extra money. This has been our family tradition,” he informs, as he unties his jhola to take out his drumming equipment — two wooden sticks. His brother Nikhil Das lends a hand. Within seconds, the two begin drumming music in alternating beats that are perfectly synchronised, without exchanging a word. The long stretch of road facing the station building gradually fills up as the day progresses, with more and more dhaakis pouring in from all over Bengal. Sukumar Das and Sadhan Bain, also from Birbhum, take a moment’s rest just after setting foot in the enclosure, before getting to work. “We started coming to Kolkata during Durga Pujo to play the dhaak only four or five years back. We are farmers, and crop yield has been low in the past few years during these months. How will we feed ourselves if we don’t do this?” Sukumar says. They both enjoy their annual city trip, which earns them anywhere between Rs 7,000 to Rs 8,000 per person for a three-week-long stint. “We stay till Kali Pujo and then leave. A teacher gives us dhaak lessons back home,” Sadhan says. [caption id=“attachment_7449051” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  A group of dhaakis putting the decorative feathers on their dhaaks[/caption] For Murshidabad’s Montu Bain, being a dhaaki comes with the perk of witnessing some of the biggest pujos from the front row. “We only just arrived so we don’t know what the demand is like this year. I guess we will find out soon, now that we will venture out and go to different pandals to play,” he says, covering his dhaak with a red towel that was wrapping his head until then in the scorching October sun. But for Debu Das — a dhaaki from Birbhum’s Mallarpur Thana — the coming weeks hold promise like every other year. “Our job isn’t affected by a failing market. Even in the age of internet and CD music, no one can take our place. They might play cassettes of pre-recorded dhaak during other festivals, but not during Durga Pujo,” he says, as he watches a man in a white shirt put up a notice in Bangla that reads: “This area is for our dhaaki friends to wait and rest in.” [caption id=“attachment_7449071” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  The enclosed space in front of Kolkata’s Sealdah Railway Station occupied by dhaakis during this time of the year[/caption] “But this is unauthorised occupation. We aren’t exactly pleased about the fact that dhaakis come and take up space in front of the station every year,” the Station Master says. However, his disapproval barely dampens the festive spirit that has already set in, welcoming visitors the moment they step into the city. Scores of weary-looking travellers lugging their bags queue in front of the enclosure, holding their phones at eye-level. [caption id=“attachment_7449081” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  A moment’s rest for a group of dhaakis outside Sealdah Railway Station[/caption] “There must be close to two thousand dhaakis arriving and gathering here on any given day during Durga Pujo,” says a Travelling Ticket Inspector, on conditions of anonymity, as he taps his feet, almost involuntarily, to the beats echoing through the air. All photos © Tanumay Naskar for Firstpost

The annual week-long carnival of Durga Puja is undoubtedly the most anticipated event in Bengal, with several seasonal jobs generated yearly because of it. Firstpost goes behind the scenes and talks to people for whom the festival is more than just a few days of celebrations — it’s their means of livelihood.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)