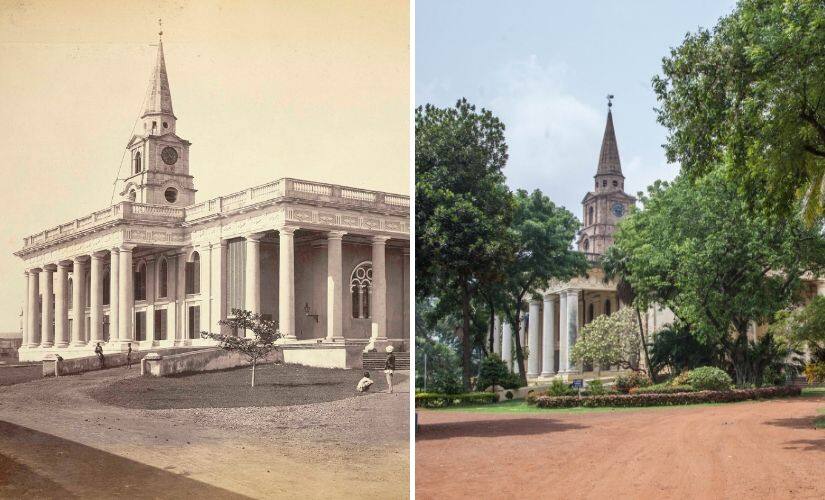

In popular culture, Kolkata’s images are dipped in sepia, while its background score slowly tunes into a scratchy gramophone record playing a Hemanta Mukhopadhyay song. For a city often heckled and burdened with charges of being stuck in time, Kolkata takes its past seriously, clinging to its yesterdays almost defiantly in a world that can’t wait to move forward. In a bid to save its profound socio-cultural heritage, ‘Envisioning the Indian City’ (ETIC), a two-year-long project (2013-2015) funded by the University Grants Commission (UGC) and UK-India Education and Research Initiative (UKIERI), propelled discussions on the “crucial role played by Indian cities in negotiating contact between India and the world, and Europe in particular.” The enterprise documented four cities: Goa, Kolkata, Pondicherry/Auroville, and Chandigarh. In addition to this, a second project enabled the development of an augmented reality app, ‘Timescape: Kolkata’, allowing people to access “rare archival images and data about heritage sites in Kolkata, as they walk through the city”. The initiative launched in 2015 was an offshoot of ETIC, funded by the University of Liverpool, and collaboratively developed by Jadavpur University and the British Library. Showcasing their work in a recently concluded, month-long exhibition at Kolkata’s Victoria Memorial Hall was 'Calcutta Collages' , an initiative of ‘Sustainable Heritage and Policy of Kolkata’ (SHPK) — a joint project undertaken by the University of Liverpool and Jadavpur University. “The tree of Calcutta’s heritage spreads out and branches in so many diverse directions that it is simply impossible to contain it all in one small room of exhibits,” says Aratrika Choudhury, curator of ‘Calcutta Collages’. Choudhury worked around the themes of “built heritage, lived spaces, and pertinent but less popular stories” while designing the exhibition. [caption id=“attachment_7102661” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Then and now — Left: St John’s Church, Calcutta, 1860s (Image courtesy: The British Library, UK. As used in the University of Liverpool-Jadavpur University Timescape app) | Right: St John’s Church, Kolkata, 2019 (Image courtesy: Kawshik Ananda Kirtania)[/caption] The idea of heritage has largely found unidimensional, almost intimidating definitions down the years, where conserving a historically significant place invariably entailed monumentalising it. This, in turn, excluded active community participation — an obstacle that projects like ETIC and ‘Timescape’ try to address from the forefront. “‘Envisioning the Indian City’ was more about looking at cities as spaces of colonial encounter. It didn’t quite focus on the heritage aspect. However, we were aware of the need to highlight the ecological heritage of the city and were very glad to have with us Sri Dhrubajyoti Ghosh (Special Advisor, Agricultural Ecosystems, Commission on Ecosystem Management, IUCN), who until his recent demise had fought tirelessly to save the East Kolkata Wetlands,” says Sujaan Mukherjee, researcher at Jadavpur University, who’s worked closely on both projects. About ‘Timescape’, Mukherjee mentions how the initiative also dabbled in the ‘digital humanities’. “The idea was to create an app that would enable people to learn more about the built environment. By pointing your phone at a building or street, you would be able to know more about the place and how it looked 150 odd years back,” he says. [caption id=“attachment_7102681” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Then and now — Left: Calcutta’s Writers’ Building many moons ago (Image courtesy: The British Library, UK. As used in the University of Liverpool-Jadavpur University Timescape app) | Right: Writers’ Building, Kolkata, 2010 (Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)[/caption] The idea of ‘sustainable heritage’ has gained currency in recent times, especially with global warming ushering in impending bionomic doom. As a result, the dialogue on conservation is not restricted to mere gentrification of structures and geographical entities anymore."‘Sustainability’ is significant for two reasons: one, in terms of conserving the built heritage — which, for any city, constitutes an incredible archive of its past. Sustainability is essential to ensure that spaces and histories that belong to the people include them in the decision-making. And secondly, sustainability is more important now than ever in the face of the ecological disasters that await us," Mukherjee points out. He cites a rather simple, yet potent example of how “building-visibility” in Kolkata has dipped with the city’s evolution, drawing one’s attention to clashing developmental and environmental goals. “One of the things we found while comparing the 19th century photographs of Calcutta with those of contemporary Kolkata, is that building-visibility was much greater in the past because there were fewer trees lining our footpaths. The increase in the number of trees on footpaths has been accompanied by the city’s own expansion at the cost of reduced greenery on its peripheries. So, to put it bluntly, do we compromise on trees for better visibility of these 19th century (and many 20th century) buildings, which were constructed with a certain optimal vantage point in mind? The answer, for me, is ’no.’ But in that case, how do we make our built heritage more visible? These are challenges that we need to address.” [caption id="" align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Then and now — Right: St Paul’s Cathedral, Calcutta, 1860s (Image courtesy: The British Library, UK. As used in the University of Liverpool-Jadavpur University Timescape app) | Right: St Paul’s Cathedral, Kolkata, 2019 (Image courtesy: Kawshik Ananda Kirtania). The spire, as seen in the old photograph, was said to have been modelled on the Norwich Cathedral. But on sustaining severe damage after the 1934 earthquake, it was rebuilt along the lines of the Bell Harry tower of Canterbury.[/caption] Additionally, the onus of generating interest in the dialogue on sustainable heritage among major stakeholders — comprising local communities, government and conservation authorities — has fallen on heritage enthusiasts undertaking initiatives that aim to not only engage people, but convince them into safeguarding their legacies too. In case of the Timescape app, the primary test lay in popularising it. “One significant challenge was in terms of the sustainability of digital technologies — it’s not enough to design an app, but to ensure that it is effective, user-friendly, and up and running is a long-term challenge,” says Dr Nandini Das of University of Liverpool, who, along with Dr Supriya Chaudhuri, Professor Emerita at Jadavpur University, initiated the projects in question. The desired long-term outcomes of the enterprises are almost directly linked to four of United Nations Strategic Development Goals, which “aim to develop actionable responses and solutions to heritage under threat, identified as a major global challenge by UNESCO,” according to Das. They also explore how such initiatives can aid in enhancing social welfare, increase economic productivity, and “support more self-reliant communities within the city of Kolkata.” Clearly, the approach towards ‘heritage’ can no longer be myopic, but a holistic one that refuses to compromise on any pressing concern whatsoever. The task at hand, therefore, is arguably daunting. “Our generation might very well know about the city’s heritage but that knowledge does not always entail active engagement. However, the scene is changing and we are seeing more and more collective and individual efforts in this direction. Dialogues are happening and results are following slowly but steadily. And this should not stop as it is an extremely important step towards preserving heritage. Heritage or all that we have inherited constitutes the city’s identity as much as new innovations and developments,” Choudhury mentions. However, in case of Kolkata, perhaps the city’s tendency to lean heavily on its past even to this day keeps it from “hitting the refresh button on its architectural legacy,” according to Mukherjee. [caption id=“attachment_7102691” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Then and now — Left: Prinsep Ghat, Calcutta, circa 1851-52 (Image courtesy: The British Library, UK. As used in the University of Liverpool-Jadavpur University Timescape app) | Right: Prinsep Ghat, Kolkata, 2010 (Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)[/caption] The urban studies scholar talks about the city’s propensity to building in “bits and patches, often covering up the urban fabric but hardly ever erasing it completely.” He adds: “Erasures have happened, but the fun part of this process, is that these stylistic layers stick to the city’s surface like palimpsests. We see many different kinds of architectural style here — the colonial British, the colonial zamindari Bengali, Indo-Saracenic, Gothic, Art Deco, and the many subtle variations that came with the different communities who gathered here (Jewish, Armenian, Scottish).” Now, at the end of the exhibition and related workshops, a comprehensive Advisory Policy Report is slated to be drawn up and prepared for publication later this year. “The report will be presented to the state government, identifying key areas that need attention and advocating best practices,” Mukherjee informs, reminding one to take a closer look at their surroundings next time. After all, ‘heritage’ isn’t exactly a thing of the past.

The dialogue on sustainable heritage has been initiated by two Kolkata-based projects: ‘Envisioning the Indian City’ and ‘Timescape: Kolkata’, which aim to address pressing issues of heritage conservation involving active community participation.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)