Belgian scholar and curator Chris Dercon, who is the former director of London’s Tate Modern, curated a programme titled ‘Convoys’ at this edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale. The programme featured films like Repetitions (Marie Andre), Die Afrikanische Frau (Alexander Kluge), The Coming Society (Susanne Kennedy, Richard Janssen), and Roi Soleil (Albert Serra), among others. At a question-and-answer session with the Kochi Biennale Foundation’s officials, he held forth on the subject of archives and the production of memory by museums, emphasising on the need to not be nostalgic. He also spoke about how the time when declarative statements about what art is good and what art is bad were made, has long ended. Here is the Q-n-A session, reproduced in full: You have spoken about rethinking the notion of a museum several times. What do you think of the possibilities of rethinking the concept of an archive today? For me, the concept of a museum is the production of memory. And today, I think we all know that collecting is becoming incredibly difficult, because the prices on the market are so high, even for the newest stuff. I must also say there is so much stuff around, so many contemporary art objects, which I think are unnecessary to collect. Then there are also many artists who don’t make collectibles at all; many artists in the East, the West and Asia, in Europe and in the United States, started to work with immaterial productions.

What is at stake is this: The museum has to rethink what it is to produce memory.

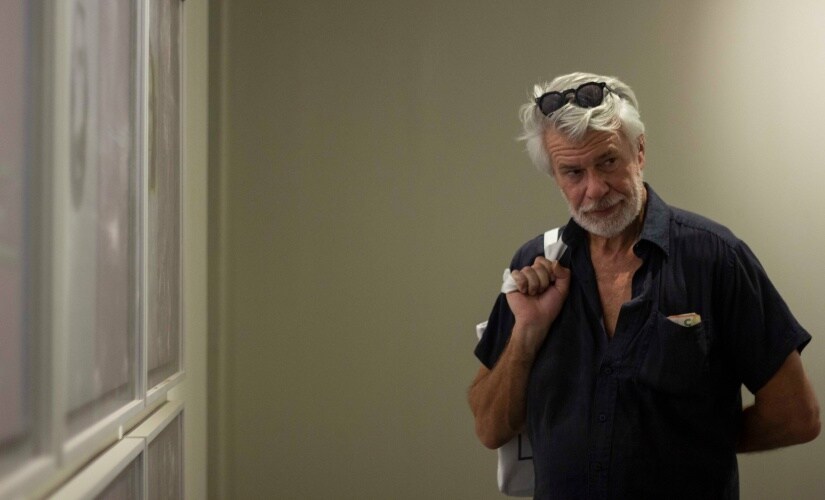

In any case, memory is not only the past but also the present and the future. Memory is a very productive kind of attitude. So-called private museums, which are like mushrooms, are blossoming everywhere – in China, but also in this country. Of course, there are some exceptions. Most of these private museums are more concerned with the here and the now than with the notion of the future. I wrote several essays on the problem of the private museum, and I understand that we need private museums where there is no government putting things in place. But when you speak to the owners of private museums, they use all sorts of words except one, which is ’the future’. We have to make a difference when we talk about a museum of the future in terms of the production of memory, between public museums and private museums because the task of the public museum is to create ownership for the public and not just for one person or a family. There, the whole notion of the archive is becoming quite important, because even if we admit that today the contemporary art object is in a crisis, that many artists are questioning the materiality of art objects and moving into the performative, we still have to find a means to do something with the past. [caption id=“attachment_5775941” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Chris Dercon. Photograph courtesy of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale[/caption] What I find very interesting is that a lot of institutions are moving into zero-money collecting. Zero-money collecting is exactly that: It is looking for many different kinds of materials which can tell stories; which can tell the story of a movement; which can tell the story of an artist; which can tell the story of a critic. It’s very important not to concentrate on the contemporary art object alone, but to make sure that you surround the object/s with many different kinds of materials. Here in India, things are getting even more interesting. Remember that Indian modernism showed this breakage, this cleavage, which is that one group — listening very carefully to what the West was saying — stated that we have to concentrate on the bazaar, on painting and sculpture. The other group — people like Tagore or Dashrath Patel — was saying we shouldn’t split things up. Today, there is an even bigger task for Indian museums in terms of the archive, because there are all kinds of objects which I would (in the sense of Tagore and Dashrath Patel) like to connect with Indian modern contemporary art production and move back into the museum. It’s an amazing challenge, because when I think about the exhibition of Dashrath Patel in Kolkata, there are so many interesting materials there which relay to Nasreen Mohamedi; they were part of this movement despite counteracting MF Hussain and Raza. “It’s all about art, and only about art,” it was said of these materials. Therefore, there are many materials and objects which could be moved into the museum, not just documentation. There is another aspect which I find very interesting, which becomes evident in this Biennale: that in India, there is still an innate sense that things don’t have to be split up — that we can inject literature, cinema, design, but that we can also inject the popular arts. Do you call it folk art, do you call it craft? I don’t think we have the right name for it yet. Because there are some artists who are so-called “outsider artists” who fit in the concept of Anita Dube so well. And they would fit in in Kiran Nadar’s museum too. Actually, Kiran Nadar is now showing an outsider artist; I don’t recall his name. He is very famous for creating murals and he died very young — actually, he committed suicide in Japan, because he couldn’t take the tension between the so-called high art and what he was forced into and where he comes from. In terms of the archive, there is a lot at stake for the future of the museum, even more so for the future of a museum in India, because of all these tensions and the different paths one can walk on. It’s very important to walk on these paths. If you want to create a museum in India, if you do a Biennale, an archive is very important, but don’t be nostalgic, don’t be obsessed and don’t fetishise the archive. A lot of artists in the West also create work about archives. I think there is too much nostalgia around the concept. It’s very unproductive to concentrate only on the past and the recent past. It’s incredibly important to look forward. On the subject of criticality and moving beyond nostalgia and engaging with a societal approach, whether it’s a museum or the archive, how important do you think constructive pedagogy is in these spaces? Incredibly important. And I like the word ‘constructive’ pedagogy, because you have many different kinds of pedagogical methods to adopt. I understand constructive pedagogy as something you develop together with an audience, with a community, with participants. The time when one would say, ‘I am going to tell you what’s good and what’s bad,’ is over. So is the time when one authority would declare, ‘This is it.’ This was good for the period when art was all about shock, awe and separation. Today, we live the art of ‘with’. Artists don’t want to play the role of geniality anymore, and I think curators should also stop playing the role of geniuses. I am afraid to say that I see many young people in India who want to become curators now instead of becoming artists, because they still believe in the authoritarian voice of the curator. So for me, the time of the geniality of the artist and the curator is over. We have to develop ideas and discourses with the audience, and this is where constructive pedagogy comes in. It’s not about passive participation or participation which I would say is a kind of fake democracy. There is another way around it, and it’s very much about decision-making processes: Who is making decisions, and how do we make decisions? I can tell you one story, about the Tate Modern when they invited Olafur Eliasson. Eliasson created this incredible orange sun in the Turbine Hall. The curators, management and the artists were confused and in a disarray after a few days because so many people had flocked to the space — many more than were expected. They started to do things themselves — they hung out, started to have picnics, take siestas, and the worst of all, the visitors started to show their own art. Of course that’s not allowed in museums. Ridiculous. What we have to learn is that there are many ways to take decisions and that we have to learn the consequences of the art of ‘with’ — that is where constructive pedagogy comes into being. You mentioned a co-productive element and that’s exactly what this edition of the Biennale looks at. How well do you think this parallels themes of representation and invisibility or marginalisation and silence? First of all, this Biennale is directed by an artist, and Anita Dube is an artist that I am absolutely fascinated by, because I often didn’t understand her, I didn’t know where her references came from. This Biennale gave me an amazing field of references to understand the work of the artist better. In this case, it is Anita Dube. References which I had never expected that she was alluding to. So that’s incredibly interesting. Anita Dube’s work allows for a kind of engagement because of the themes chosen and because you know that she has chosen her peers, many of whom are women, but not women alone. Her work allows for a process of identification, not so much for a process of distancing. She tries to communicate. She tries to — and that’s the most important aspect — in order to make a contribution. When I was teaching (I still give lectures to artists), artists would come up to me and say, ‘We would like to follow your course, to go to this art school, that art school.’ I would always say to them, what do you want? Some would reply, ‘We want to be able to express ourselves.’ I doubt if that’s necessary. I think an artist today has to, in the first place, make a contribution. And that’s what this Biennale is doing. Anita Dube has invited so many artists who believed or who believe in and who made and continue to make contributions. So in a way, they make necessary art. Because there is so much art which is totally unnecessary today, even in India.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)