If you’re clued in to the global food scene or food writing, it’s hard to miss Mayukh Sen: Apart from bylines in The New York Times and New Yorker, the 27-year-old writer has won two awards in the last year — a James Beard Award for his story on Princess Pamela, a soul food sensation, and an IACP Award for an article on Felipe Rojas-Lombardi, “the gay man who brought tapas to America”. It’ll probably be hard to miss him at a dinner table too. Though he is a Bengali (cue: gasp), he does not eat fish — because he’s allergic to it. Sen has developed a voice of his own — a sensitive style of storytelling about subjects who are lesser-known or those who have faded into oblivion, while taking into account facets of identity like sexuality, race and ethnicity. He didn’t set out to become a food writer, though; he grew up wanting to be a film critic. He didn’t cook much, and his memories of food were closely tied to his mother’s Bengali cooking and stray visits to chain restaurants like The Cheesecake Factory and PF Chang’s. Writing about food on the job and going freelance after winning the James Beard Award made him realise how much he cherished the subject. He’s now working on a book about immigrant women who have contributed to America’s food culture. In this conversation with Firstpost, he talks about the book, where politics intersects with food and whether influencer content is eating into long-form about food. [caption id=“attachment_6755661” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Mayukh Sen. Photograph by Jason Favreau[/caption] Where did the idea for your upcoming book come from? Two summers ago, a friend suggested I write a book using food as a way to complicate narratives surrounding immigrant lives in America. I was troubled by the overt demonisation of immigrant lives from the Right, and I was also disturbed by the liberal impulse to apply patronising narratives to immigrants, measuring their value in terms of their output. I thought that the best way to work against both dangerous lines of thought was to focus on the granular stories of individual immigrants who worked in food.

So much of my work focuses on food’s forgotten figures, particularly women.

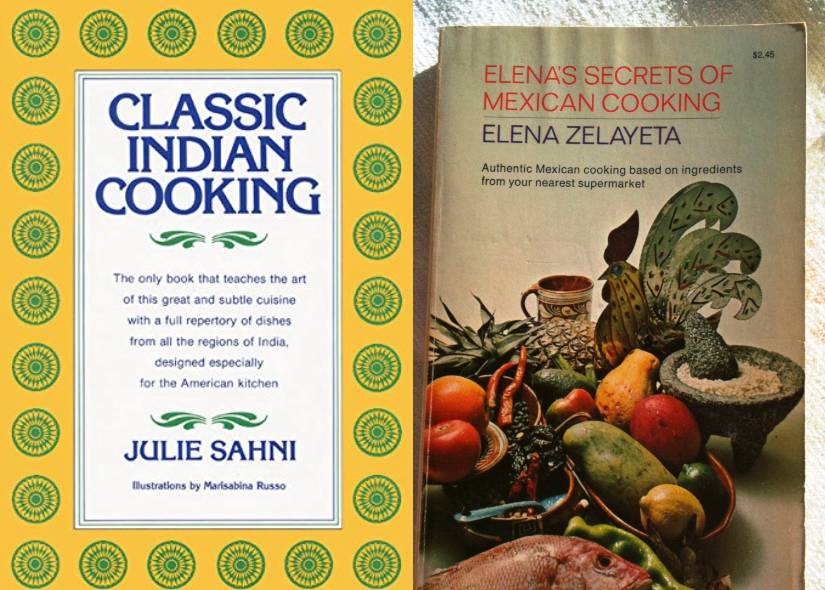

I thought it was only natural that I apply that template to my book and make it about seven different immigrant women who’ve shaped food throughout American history. Most are deceased; some are more well-known than others. Tell us about two of the women who will be featured in this book. I’m devoting one chapter to Elena Zelayeta, the Mexican-born cookbook author who came to the United States in her early teens in the early 20th century. She became blind as an adult, which is, funnily enough, when her culinary career really took off. Hers is a remarkable story of resilience. For a time, she was the American authority on Mexican cooking, yet her legacy has fallen through the cracks for reasons I’ll examine in my book. I am also writing about the great Julie Sahni, an Indian cookbook author whose first book, Classic Indian Cooking, came out in 1980. Sahni isn’t discussed nearly enough as she should be; she was an incredibly accomplished dancer, particularly in Bharatanatyam, in India, and she nearly pursued a career in film before abandoning it for architecture. (Food came later.) [caption id=“attachment_6755651” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Books by Julie Sahni and Elena Zelayeta[/caption] You’ve won two awards for your writing. What does this mean for your own work, and for writers of colour and non-binary/queer folk? Do you see a shift in the idea of ‘who a food writer is’ in America? I can only speak for myself, but winning the James Beard Award in particular has given me access to greater opportunity and capital to keep doing the work I care about. It has also allowed me to command a baseline level of respect from gatekeepers that I had to fight for before this. As for what these awards mean beyond me — well, queer writers and writers of color have always existed in our field, but it’s gratifying to see more of them, like myself, being recognised by an establishment that may have once felt impermeable to many of us. I’m seeing a marginal shift in whom the culinary establishment now regards as a food writer worthy of respect. The shift is slow, though, and the work isn’t done. Many of the writers of color major publications give bylines to come from comfortably middle-class backgrounds (myself included). I’d like to see more class perspectives represented in American food writing. Do you think that the lack of credit given to immigrant women who contributed to American food is emblematic of a larger discriminatory attitude in the country? Absolutely: Some of the women I’m writing about, particularly those from the global South, came to America and began writing about food in times when gatekeepers didn’t consider the cuisines they represented worthy of respect, especially against the tyranny of Continental European food. This lack of respect often reflected larger political and cultural mores. I’m thinking of Najmieh Batmanglij, the Iranian cookbook author who came to America just after the Iranian Revolution and the hostage crisis, meaning she couldn’t even sell a book on Iranian food. Another woman I am hoping to write about, France’s Madeleine Kamman, had the audacity to criticise Julia Child, a darling of food. Kamman is an example of someone who was not the “right” kind of immigrant for the culinary world to embrace. She was unruly and openly critical of idols like Child who most felt were beyond criticism. Kamman rejected the docility that people likely expected of her as an immigrant woman. What place do you think politics and identity have in food? There are a number of ways I could answer this question, but, as it applies to my own work, politics and identity are inextricable from discussions of what stories the culinary establishment deems important and who gets remembered in retellings of culinary history. Discussion of such topics as race, gender, and sexuality may disturb readers who seek sanctuary in food writing, people who regard food writing as a break from everything awful going on in the world, but they’re kidding themselves.

There’s both pain and pleasure in the story of how our food gets to us.

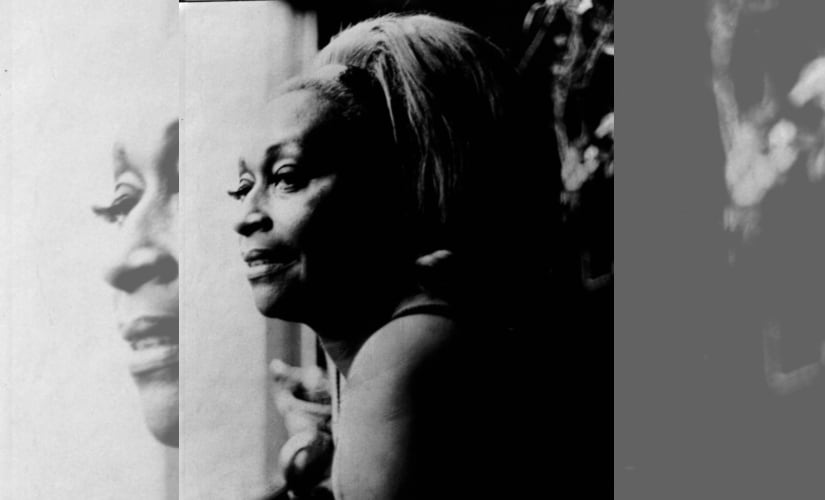

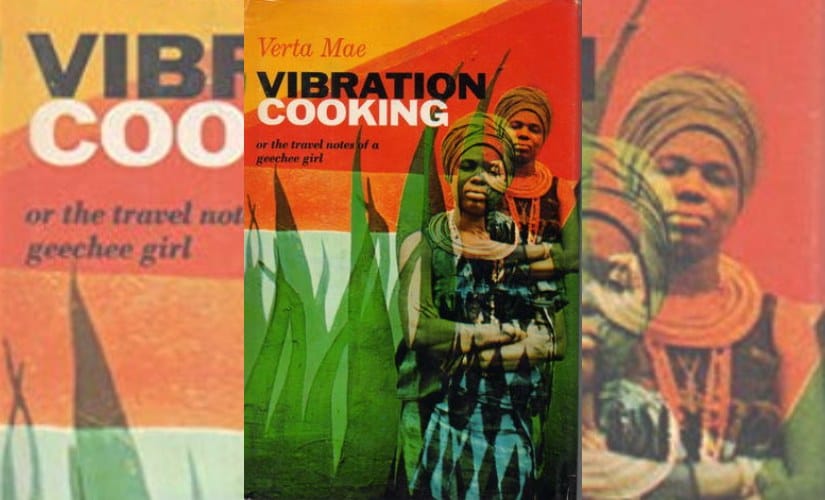

Food writing provides the opportunity to address this entire spectrum. [caption id=“attachment_6755671” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Princess Pamela[/caption] I would be underplaying it severely if I said food/lifestyle influencers are big in India. Do you see influencer content as eating into the space for long-form on food? Or are they very separate? I can only speak from an American perspective, but I certainly do fear that there’s a conflation of the work of influencers with truly strong, boundary-pushing food journalism. In the past year, I’ve seen a number of influential food publications invest in talents who pander to the lowest common denominator. It’s happening with Indian food — some of our most visible figures in the diaspora come from incredibly privileged, high-caste backgrounds and speak with false authority on the varied foodways of India. The blame doesn’t fall entirely on these folks. The editors enabling such people don’t have the cultural acuity to push them to do more precise work. But it’s alarming seeing such work, reverse-engineered to go viral, infiltrate publications I otherwise respect. Food has long been a motif in Indian diaspora (fiction) writing. Do you think it will ever turn into a cliché, or does it have an enduring allure? Depictions of food in diaspora fiction feel cliched when they’re aligned with tropes of magic or mysticism, or, worse, when writers treat food as a portal to the past, recalling an imagined Indian homeland that authors look at from an uncomfortably romantic remove. Food can also convey that tired narrative of someone caught between two worlds, Indian and Western, relying on a binary that feels far too simplistic to be compelling in 2019. Naben Ruthnum, author of Curry: Eating, Reading, and Race, wrote about this very intelligently. One way diaspora fiction can resist such cliche is to make sure that the writers come from more diverse caste and regional backgrounds, and that commissioning editors are smart enough to be looking for stories that push against these worn tropes. [caption id=“attachment_6755721” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  I often revisit Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor’s Vibration Cooking, a 1970 cookbook/memoir, says Sen[/caption] A lot of your writing is centered on subjects who have died, or whose legacy has been lost or is unknown. Do you think there’s a particular reason you are drawn to such stories? My gravitation to stories of people who’ve died or been lost to history has a lot to do with the death of my father in 2017 — he’d been sick since I was a child, but his cancer diagnosis came in my senior year of college, just as I was beginning my career as a writer. My own cognisance of the fact that I would have to be dealing with a reality without him informed my writing in ways I’m only now starting to understand. There is so much about him that I’ve forgotten about him since his death, like his voice and mannerisms.

Everyone experiences loss. I want to capture these memories of other figures people have lost, because I understand how easily those memories can evaporate if no one writes them down.

I like to think I’m honoring my father through my work in some way.

Mayukh Sen’s favourite… Cook-book — Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor’s Vibration Cooking Food writer — Ruby Tandoh (wo began her career as a contestant on the Great British Bake-Off) Cuisine — Ethiopian, by far Indian dish — Begun bhaja Celebrity chef — Edna Lewis

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)