Saint Petersburg is one of the most spectacularly beautiful cities in the world. Situated on the

Neva River

, at the head of the

Gulf of Finland

on the

Baltic Sea

, it was founded by

Tsar

Peter the Great

in in 1703. In 1914, the name was changed from Saint Petersburg to Petrograd, in 1924 to Leningrad, and in 1991 back to Saint Petersburg. Between 1713 and 1728 and in 1732–1918, St. Petersburg was the capital of imperial Russia. In 1918, the central government bodies under the Soviets moved to Moscow. St. Petersburg is home to

The Hermitage

, one of the largest

art museums

in the world. Many of Russia’s greatest cultural figures (like Fyodor Dostoyevsky) lived in this city at some point in their lives and their homes, which are still standing, have been turned into museums. In the street behind the hotel where I was put up, for instance, was the Nabokov Museum, located in the city apartment in which the author of Lolita spent part of his childhood. The cultural life of the city is vibrant and a visit to its museums, exhibitions or even one of its cafes lets you see it. The churches too are grand, with St Isaac’s Cathedral and The Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood leading the way. [caption id=“attachment_4239443” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Saint Petersburg by night. Photo courtesy Aleksey Smalianchuk, freeimages[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_4239447” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Saint Petersburg by night. Photo courtesy Aleksey Smalianchuk, freeimages[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_4239447” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Photo courtesy Witek Burkiewicz, freeimages[/caption] I was in the city for a colloquium devoted to recent Russian cinema (between 13-15 November; a prelude to the Saint Petersburg International Cultural Forum) for members of FIPRESCI, the international federation of film critics with its central office in Munich. I was representing FIPRESCI’s Indian chapter; there were also film critics from the US, UK, Brazil, Turkey, Holland, France, Israel, Serbia, Australia and Canada present at the Lenfilm Studio screenings. On the last day, was the actual colloquium, moderated by leading Russian film critic Andrei Plakhov. Russia’s contribution to cinema has been monumental but because of the isolationist policy the Soviet government followed, Russian cinema itself is not known widely. Barring a few film-makers like Andrei Tarkovsky, few are familiar with the Soviet/Russian cinema of the Brezhnev. This is regrettable, since Russian films of the last three decades of the 20th century represent a substantial chunk of the greatest in world cinema. Russian directors like Alexey German and Alexey Balabanov are only now receiving a small part of the international attention justly due to them. Russia has VGIK, perhaps the greatest film school in the world, and the students who pass out of it consistently demonstrate their competence. The FIPRESCI screenings began on the first day with restored version of Balabanov’s Of Freaks and Men (1998), filmed in sepia. It is about the early days of cinema in Russia, but where such a film would normally celebrate the arrival of a new technology (eg: Stanley Donen’s Singing in the Rain, 1952), Of Freaks and Men deals with how cinema is used for pornography. Since cinema is still in its primitive period, the protagonist specialises in short pieces of pornography which demand little sophistication – all they show are the bare behinds of young women being whipped by a nanny. Other characters in the film include a young pair of Siamese twins, who are also used in the protagonist’s erotic shorts. Balabanov’s film is dependent on recognition that the immediate use of any new technology could be for pornography; and, if anything, the internet demonstrates it. ‘Russia’ conjures up in our imagination a single culture, but here one saw films coming from ethnic minority groups. Kostas Marsan’s Yakut film My Killer – a crime thriller – was also screened on the first day. The second day was devoted to art-house cinema and the work of senior directors, such as the Uzbek-born Rustam Khamdamov (The Bottomless Bag) and Boris Khlebnikov (Arrythmia). Khamdamov’s film is part fairy-tale while Khlebnikov’s film deals sensitively with a marriage under strain. But more impressive than either of these were two films by youngsters – Kantemir Balagov’s Closeness and Alexandr Khant’s How Victor ‘the Garlic’ took Aleksei ‘the Stud’ to the Nursing Home. [caption id=“attachment_4239453” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Photo courtesy Witek Burkiewicz, freeimages[/caption] I was in the city for a colloquium devoted to recent Russian cinema (between 13-15 November; a prelude to the Saint Petersburg International Cultural Forum) for members of FIPRESCI, the international federation of film critics with its central office in Munich. I was representing FIPRESCI’s Indian chapter; there were also film critics from the US, UK, Brazil, Turkey, Holland, France, Israel, Serbia, Australia and Canada present at the Lenfilm Studio screenings. On the last day, was the actual colloquium, moderated by leading Russian film critic Andrei Plakhov. Russia’s contribution to cinema has been monumental but because of the isolationist policy the Soviet government followed, Russian cinema itself is not known widely. Barring a few film-makers like Andrei Tarkovsky, few are familiar with the Soviet/Russian cinema of the Brezhnev. This is regrettable, since Russian films of the last three decades of the 20th century represent a substantial chunk of the greatest in world cinema. Russian directors like Alexey German and Alexey Balabanov are only now receiving a small part of the international attention justly due to them. Russia has VGIK, perhaps the greatest film school in the world, and the students who pass out of it consistently demonstrate their competence. The FIPRESCI screenings began on the first day with restored version of Balabanov’s Of Freaks and Men (1998), filmed in sepia. It is about the early days of cinema in Russia, but where such a film would normally celebrate the arrival of a new technology (eg: Stanley Donen’s Singing in the Rain, 1952), Of Freaks and Men deals with how cinema is used for pornography. Since cinema is still in its primitive period, the protagonist specialises in short pieces of pornography which demand little sophistication – all they show are the bare behinds of young women being whipped by a nanny. Other characters in the film include a young pair of Siamese twins, who are also used in the protagonist’s erotic shorts. Balabanov’s film is dependent on recognition that the immediate use of any new technology could be for pornography; and, if anything, the internet demonstrates it. ‘Russia’ conjures up in our imagination a single culture, but here one saw films coming from ethnic minority groups. Kostas Marsan’s Yakut film My Killer – a crime thriller – was also screened on the first day. The second day was devoted to art-house cinema and the work of senior directors, such as the Uzbek-born Rustam Khamdamov (The Bottomless Bag) and Boris Khlebnikov (Arrythmia). Khamdamov’s film is part fairy-tale while Khlebnikov’s film deals sensitively with a marriage under strain. But more impressive than either of these were two films by youngsters – Kantemir Balagov’s Closeness and Alexandr Khant’s How Victor ‘the Garlic’ took Aleksei ‘the Stud’ to the Nursing Home. [caption id=“attachment_4239453” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

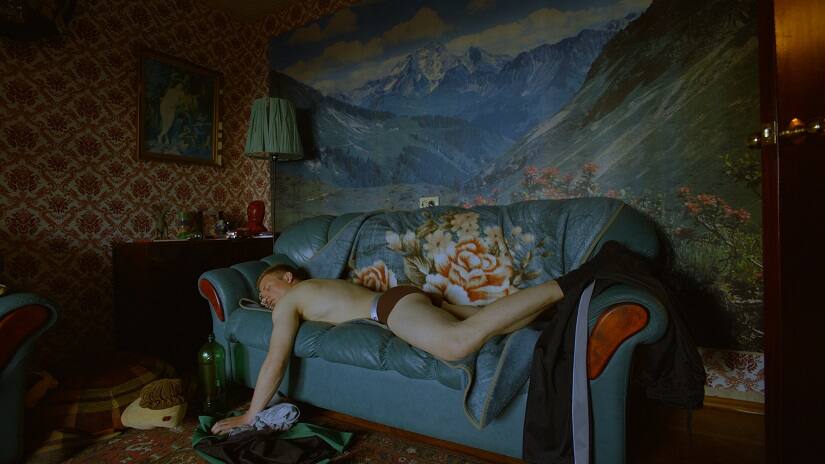

Still from Kantemir Balagov’s Closeness[/caption] Balagov’s film (the director is only 26 years old) is set in a small town in a region bordering Chechnya (Nalchik, Northern Caucasus) at the time of the Chechen war around 1998. It deals with a minority Jewish family in a Muslim majority area. The son of the house is kidnapped with his girlfriend for ransom and the family needs to raise money. The Jewish community contributes but the money raised is only adequate to get the girl released. The family decides to get the daughter of the house, Adina, married to a richer Jewish family – but Adina has a Muslim boyfriend, and she responds by losing her virginity to him. Religious identity is not an important issue in Russia because of decades of communism but it has begun to make its presence felt here when Muslims and non-Muslims side with Chechnya and Russia respectively. Closeness, like My Killer, is not in Russian but in a minority language – Kabardian. The film might have become an ethnographic exercise but it creates a powerful fictional situation and grips the viewer. Balagov’s film was made consequent to a local workshop conducted by celebrated Russian director Alexandr Sokurov. On the other hand, Alexandr Khant (who is 32) is a VGIK graduate, having studied under Karen Shakhnazarov, now director-general of Mosfilm. How Victor ‘the Garlic’ took Alexey ‘the Stud’ to the Nursing Home may be described as a road movie and deals with two sociopaths, father and son. Victor grew up in an orphanage after his mother’s death since his father Alexey abandoned the family. Victor has a wife and son but he is wild, prone to acts of gratuitous violence and seeks to buy an apartment in which to install his mistress. It is at this inopportune moment that his long-lost father abruptly resurfaces as a retired criminal, virtually at death’s door but owning an apartment Victor could inherit. It turns out that Alexey is not in such a bad shape and Victor is to take him to an old people’s home, the only one which will have him – being in another city far away. As the two embark upon their journey, Alexey decides to introduce his son to various other people in his life, including another wife and child and former associates in crime, although certain death awaits him at the latters’ hands. What was deeply intriguing in Khant’s film is the sense of honour among criminals superseding legality as a moral force, perhaps a subtle way of showing the weakening moral authority of the dictatorial state. [caption id=“attachment_4239455” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Still from Kantemir Balagov’s Closeness[/caption] Balagov’s film (the director is only 26 years old) is set in a small town in a region bordering Chechnya (Nalchik, Northern Caucasus) at the time of the Chechen war around 1998. It deals with a minority Jewish family in a Muslim majority area. The son of the house is kidnapped with his girlfriend for ransom and the family needs to raise money. The Jewish community contributes but the money raised is only adequate to get the girl released. The family decides to get the daughter of the house, Adina, married to a richer Jewish family – but Adina has a Muslim boyfriend, and she responds by losing her virginity to him. Religious identity is not an important issue in Russia because of decades of communism but it has begun to make its presence felt here when Muslims and non-Muslims side with Chechnya and Russia respectively. Closeness, like My Killer, is not in Russian but in a minority language – Kabardian. The film might have become an ethnographic exercise but it creates a powerful fictional situation and grips the viewer. Balagov’s film was made consequent to a local workshop conducted by celebrated Russian director Alexandr Sokurov. On the other hand, Alexandr Khant (who is 32) is a VGIK graduate, having studied under Karen Shakhnazarov, now director-general of Mosfilm. How Victor ‘the Garlic’ took Alexey ‘the Stud’ to the Nursing Home may be described as a road movie and deals with two sociopaths, father and son. Victor grew up in an orphanage after his mother’s death since his father Alexey abandoned the family. Victor has a wife and son but he is wild, prone to acts of gratuitous violence and seeks to buy an apartment in which to install his mistress. It is at this inopportune moment that his long-lost father abruptly resurfaces as a retired criminal, virtually at death’s door but owning an apartment Victor could inherit. It turns out that Alexey is not in such a bad shape and Victor is to take him to an old people’s home, the only one which will have him – being in another city far away. As the two embark upon their journey, Alexey decides to introduce his son to various other people in his life, including another wife and child and former associates in crime, although certain death awaits him at the latters’ hands. What was deeply intriguing in Khant’s film is the sense of honour among criminals superseding legality as a moral force, perhaps a subtle way of showing the weakening moral authority of the dictatorial state. [caption id=“attachment_4239455” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Still from Alexandr Khant’s How Victor ‘the Garlic’ took Aleksei ‘the Stud’ to the Nursing Home[/caption] The last day’s screenings at Lenfilm were devoted to Russian mainstream cinema and the three films screened were Klim Shipenko’s Salyut 7, a space adventure like Gravity (2013) but based on an actual event, Aleksey Uchitel’s Mathilde, a historical costume drama about Tsar Nicholas II’s relationship with a ballet-dancer and Fedor Bondarchuk’s Attraction, an alien-landing film in which the aliens are shown to be morally superior to humans. All three films demonstrated the highest levels of technical competence, although their budgets were often only around 10 percent of what a similar film might cost in Hollywood. Still, while the films are all meant to be international blockbusters, one sees them catering mainly to a local public. Language could come in the way of larger appeal but, more importantly, while Russian actors are excellent they are not groomed to be stars in the Hollywood way. Where the star draws the spectator to identify with him/her, Russian acting seems unable to facilitate it. The directors attending the colloquium seemed to understand this because an issue brought up by director Fedor Bondarchuk (son of Sergei Bondarchuk who made War and Peace, 1966) was whether non-Russian stars could not be brought into Russian mainstream films to enhance their appeal. But then, it was pointed out, Russian films could lose their ‘Russian’ appeal, which was why people loved them. The Saint Petersburg International Cultural Forum (which began on 15 November) included some film-related events – among them, a Tarkovsky exhibition which included paintings and sketches by the great filmmaker, including designs for films like Solaris (1972). Another important event was the centenary celebration of Fedor Khitruk, the father of Russian animation. Khitruk was a very versatile animator who is best known for his ‘Winnie the Pooh’ films based on AA Milne’s immortal character. Russian animation is virtually unknown in India but it has reached a level of sophistication rarely matched. The Japanese master of animation Hayao Miyazaki (Spirited Away, 2001) is an ardent admirer of Russian veteran Yuri Norstein, who was present at the Fedor Khitruk opening. Norstein has been at work for years on an animated version of Gogol’s story The Overcoat, amazing bits of which

can be found on YouTube

. [caption id=“attachment_4239457” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Still from Alexandr Khant’s How Victor ‘the Garlic’ took Aleksei ‘the Stud’ to the Nursing Home[/caption] The last day’s screenings at Lenfilm were devoted to Russian mainstream cinema and the three films screened were Klim Shipenko’s Salyut 7, a space adventure like Gravity (2013) but based on an actual event, Aleksey Uchitel’s Mathilde, a historical costume drama about Tsar Nicholas II’s relationship with a ballet-dancer and Fedor Bondarchuk’s Attraction, an alien-landing film in which the aliens are shown to be morally superior to humans. All three films demonstrated the highest levels of technical competence, although their budgets were often only around 10 percent of what a similar film might cost in Hollywood. Still, while the films are all meant to be international blockbusters, one sees them catering mainly to a local public. Language could come in the way of larger appeal but, more importantly, while Russian actors are excellent they are not groomed to be stars in the Hollywood way. Where the star draws the spectator to identify with him/her, Russian acting seems unable to facilitate it. The directors attending the colloquium seemed to understand this because an issue brought up by director Fedor Bondarchuk (son of Sergei Bondarchuk who made War and Peace, 1966) was whether non-Russian stars could not be brought into Russian mainstream films to enhance their appeal. But then, it was pointed out, Russian films could lose their ‘Russian’ appeal, which was why people loved them. The Saint Petersburg International Cultural Forum (which began on 15 November) included some film-related events – among them, a Tarkovsky exhibition which included paintings and sketches by the great filmmaker, including designs for films like Solaris (1972). Another important event was the centenary celebration of Fedor Khitruk, the father of Russian animation. Khitruk was a very versatile animator who is best known for his ‘Winnie the Pooh’ films based on AA Milne’s immortal character. Russian animation is virtually unknown in India but it has reached a level of sophistication rarely matched. The Japanese master of animation Hayao Miyazaki (Spirited Away, 2001) is an ardent admirer of Russian veteran Yuri Norstein, who was present at the Fedor Khitruk opening. Norstein has been at work for years on an animated version of Gogol’s story The Overcoat, amazing bits of which

can be found on YouTube

. [caption id=“attachment_4239457” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Downtown St Petersburg. Photo courtesy Michael Sult, freeimages[/caption] The inaugural ceremony of the Saint Petersburg International Cultural Forum was held on the second day and included the premier of Petrushka, a short ballet (about the loves and jealousies between three puppets in a puppet theatre) with music by Igor Stravinsky, running to about 40 minutes. The programme for the inaugural ceremony was not revealed in advance and abruptly, Vladimir Putin himself made an appearance and delivered a five-minute speech after which the performance of Petrushka commenced. I later saw him sitting barely 20 feet from me, being discreetly watched over. A visit to Russia can be very revealing, especially given the negative publicity the country gets in the world press. A feature one notices when one meets Russians is how deeply the educated are steeped in their country’s culture, especially their grounding in literature and the arts. I attribute this to the people still being kept out of conspicuous consumption because of the economic conditions imposed upon them. Saint Petersburg itself, while being among the grandest of cities, is also not the tourist haunt that Florence, Paris or Prague has become. The people one sees on the streets are mostly locals and that makes no small contribution to its authentic charm. The city truly deserves its title of being Russia’s cultural capital. [caption id=“attachment_4239459” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Downtown St Petersburg. Photo courtesy Michael Sult, freeimages[/caption] The inaugural ceremony of the Saint Petersburg International Cultural Forum was held on the second day and included the premier of Petrushka, a short ballet (about the loves and jealousies between three puppets in a puppet theatre) with music by Igor Stravinsky, running to about 40 minutes. The programme for the inaugural ceremony was not revealed in advance and abruptly, Vladimir Putin himself made an appearance and delivered a five-minute speech after which the performance of Petrushka commenced. I later saw him sitting barely 20 feet from me, being discreetly watched over. A visit to Russia can be very revealing, especially given the negative publicity the country gets in the world press. A feature one notices when one meets Russians is how deeply the educated are steeped in their country’s culture, especially their grounding in literature and the arts. I attribute this to the people still being kept out of conspicuous consumption because of the economic conditions imposed upon them. Saint Petersburg itself, while being among the grandest of cities, is also not the tourist haunt that Florence, Paris or Prague has become. The people one sees on the streets are mostly locals and that makes no small contribution to its authentic charm. The city truly deserves its title of being Russia’s cultural capital. [caption id=“attachment_4239459” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

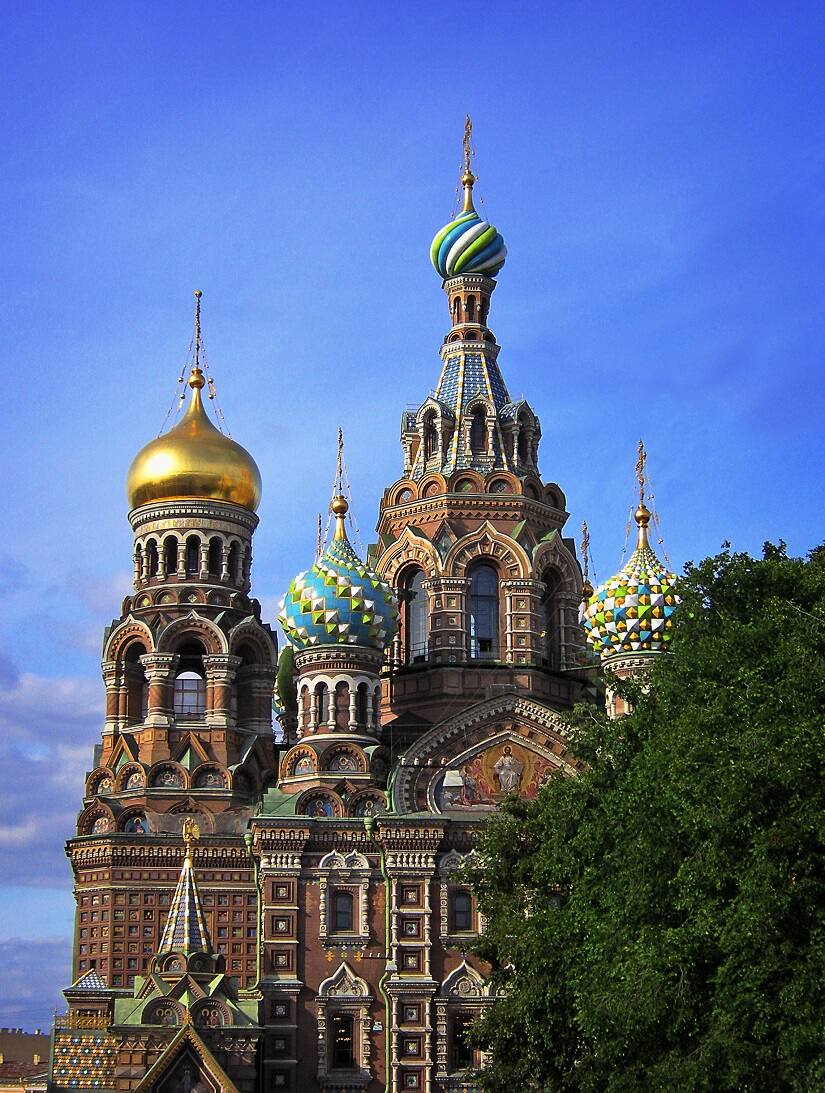

A glimpse of the Saint Basil’s Cathedral, perhaps St Petersburg’s most recognisable monument. Photo courtesy Natalia R, freeimages[/caption] MK Raghavendra is a film scholar and author of seven books including The Oxford India Short Introduction to Bollywood (2016). He is deeply interested in social, political and cultural issues in India, an interest that informs his books on film.

A glimpse of the Saint Basil’s Cathedral, perhaps St Petersburg’s most recognisable monument. Photo courtesy Natalia R, freeimages[/caption] MK Raghavendra is a film scholar and author of seven books including The Oxford India Short Introduction to Bollywood (2016). He is deeply interested in social, political and cultural issues in India, an interest that informs his books on film.

In St Petersburg, courting culture, Russian cinema, and a chance sighting of Vladimir Putin

MK Raghavendra

• December 3, 2017, 10:11:29 IST

In St. Petersburg, uncovering a little bit of Russia through its cinema | #FWeekend

Advertisement

)

End of Article