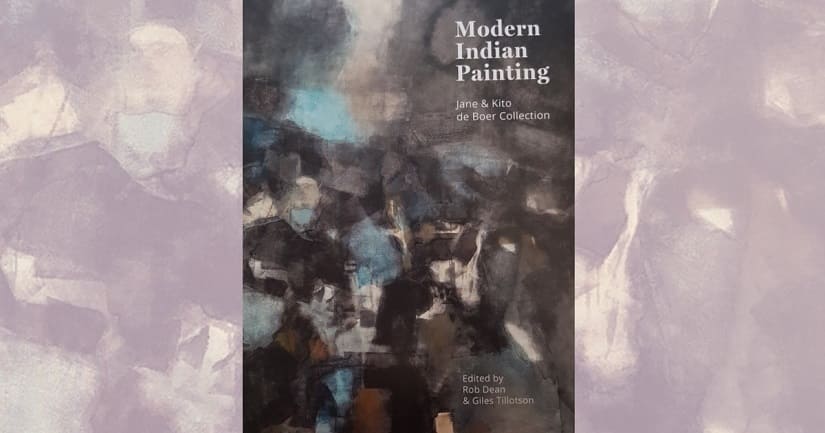

In early 1994, when Jane and Kito de Boer had settled in India, they had a confrontation with a work of art by an Indian modernist painter at the erstwhile Kumar Gallery in Delhi. “We were at the opening of an exhibition at a point when we were just finding our feet in the city,” they recount in Modern Indian Painting, a new book premised on their collection. “We knew nothing of India’s art: we had never heard of Husain or Souza. Paintings were purely images shorn of any contextual meaning. We had no intention of buying, let alone starting a collection.” The couple was socialising, chatting with a stranger, when they encountered on a wall across the room, Ganesh Pyne’s ‘Lady before the Pillar’. “It was a magical moment: the work cast a spell on us. It was too expensive and too strange to simply buy on the spot. We went home and talked about it. We went back to the gallery to find out more. We went back to see if the spell continued. We went back again to negotiate. We went back to bring her home. She is still with us. She has hung on our walls ever since. The spell she casts is a strong as ever.” Spread across New Delhi, London and Dubai, Jane and Kito de Boer’s collection of modern Indian painting includes at least 1,000 works, making it among the largest of its kind in private hands. The recently released tome, published by Mapin, and edited by Rob Dean and Giles Tillotson, offers a glimpse into the collector couple’s methodology, passion, and commitment, while simultaneously proposing an art historical understanding of the relevance of their significant collection and contribution. Modern Indian Painting carries essays by Partha Mitter, chronicling the rise of artistic nationalism in India, a brief treatise on the role of the Progressive Artists Group by scholar, Yashodhara Dalmia, while Giles Tilotson recounts some early episodes in the history of modern Indian art and Sona Datta examines art in Bengal post Independence. Besides insightful interviews with Jane and Kito de Boer, the book also boasts a section featuring rare and intimate conversations with artists like Ganesh Pyne, A Ramachandran and Rameshwar Broota. While in Mumbai to launch the book, we caught up with Jane and Kito de Boer over a telephone call to learn more about their collecting philosophy. Edited excerpts. [caption id=“attachment_6503511” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Jane and Kito de Boer[/caption] In the course of your journey as collectors, did you find yourselves spending time in artists’ studios? Kito: Most of the work that you’ll see that we’ve collected, the artists have passed away, but there were some artists we got to know quite well. Broota and Ramachandran were the two more important. They were Delhi-based and became good friends of ours. Ganesh Pyne was always more elusive, he was based in Kolkata, we met with him and got to know him better, but I would never say well. [MF] Husain we met on many occasions, but he also ended up living in Dubai, not far from us, so we’d meet him there a lot. As for Biren De, Ram Kumar, Manjit Bawa, I don’t think we got to know them beyond the cocktail circuit. We went to Ramachandran’s studio a lot, with his wife, Chameli. The meetings with them were important, to understand their work better. Ramachandran in particular is a great mind, and a great scholar, with a deft understanding, who has thought through a lot of what he does and why he does it. It’s important to hear him to understand what he did, in order to interpret the work he does, which can appear to be quite decorative. Jane: We had a history of not being able to afford what we liked in terms of art. Then we moved to India, and there was work we could afford that we liked. Ours was a history of looking at galleries, spending a lot of time in museums, a history of collection. What was attractive was that we were able to have personal interactions with the artists. The first time I saw Broota, I was bowled over, I asked the gallerist, Renu Modi, if it would be possible to meet him, and we did. As witnesses to the evolution of modern Indian art, what are some of your observations? Kito: It’s certainly grown. But compare it to Europe or the States, where you see the gallerists working very hard to support, promote and bring their artists to the outside world, I see less of that being done in India with that long-term view. When you go to Hauser &Wirth, for instance, they take a five-to-10-year view of building an artist, it’s a process, and they work hard to place work in institutions. It’s a lot of patient building. [caption id=“attachment_6503521” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Cover for Modern Indian Painting[/caption] Jane: In terms of public infrastructure and even within private galleries, we haven’t seen huge change. The best new museum in India is of course Kiran Nadar’s, which is fantastic, but it’s a private individual who is doing that. That is a change, but particularly we’ve seen a difference between China and India. Kito: The main point we’re trying to make is the lack of public infrastructure and support for the arts. Since the mid ’60s, China made art and culture a strategic industry, a part of their five-year plans; they recognised that you’re not going to be taken seriously as a country until you’re taken seriously as a culture. Sure, you’re known for making low-cost sneakers and T-shirts, but that’ll take you only so far. India, on the government level, hasn’t been able to look at culture as a strategically important industry. They’re not going to get distracted by “light-weight stuff” like arts and culture. It’s a shame, because many people look at other countries through that lens and therefore take them seriously. Some of the biggest cultural contributions to the world have come from India. In the ICC Cricket World Cup, if India wasn’t playing it would be unthinkable; in culture — because it has the greatest culture — it should be up there with the greatest. How would you describe the rise of the category of the private Indian collector? Kito: When we started, art was not something that you did or got involved in because it was an investment. Artists became artists despite the wish of their parents and society, by and large. And the collectors that existed were ones like the Tatas… they bought very good works, they put them into their institutions, they were collectors that were respected and were very respectable. In our journey, we moved during the period of art not being investment, then going to the frenzy of the investment bubble, where people began to think of art not just as art but as a commodity, and you started getting collectors moving in with a whole variety of motivations. I guess that’s a good thing. One shouldn’t be judgmental. Everybody has their own reasons for getting in which can evolve over time. The striking thing, if you contrast it to China, to Indonesia, to Singapore, in those countries, if you are a wealthy family, you are almost certainly going to be a patron of the arts. There’s a lot of data on the proportion of people’s assets in art collections amongst high net-worth individuals. In India, it’s much lower. In India, you really only have half a dozen at best — Kiran Nadar and the others. We’re happy we’ve got Kiran and a few others, but in reality, in a nation of 1.2 billion, with all the works we have, it’s strikingly under-developed. Why aren’t there more people like the Piramals… we spent four hours with their collection… why aren’t there 10-12-15-20 of these families? India has great families with great means, but it’s surprising that many are holding back. We’ve only just started to explore and develop the Indian art market.

Spread across New Delhi, London and Dubai, Jane and Kito de Boer’s collection of modern Indian painting includes at least 1,000 works, making it among the largest of its kind in private hands. A recently released book offers a glimpse into the collector couple’s methodology, passion, and commitment, while simultaneously proposing an art historical understanding of the relevance of their significant collection and contribution.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)