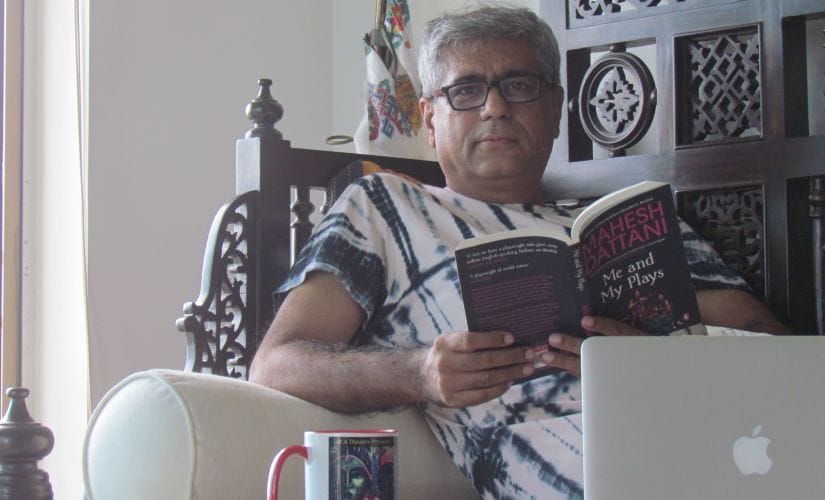

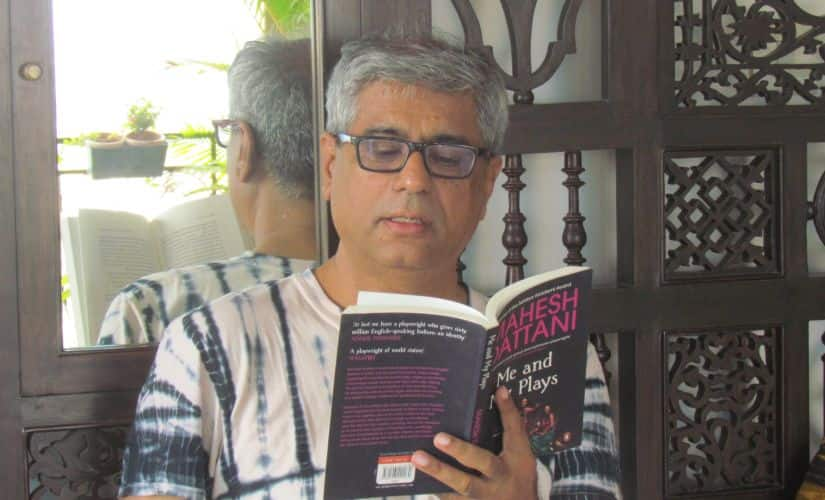

Editor’s note: This interview is part of a series where playwrights talk about the struggles of writing and staging their script/s. *** “Will you have chai with milk?” reads the text message, 12 minutes before I’m scheduled to reach his house. Turns out a perfect cup of ginger masala tea (not cardamom, and he gets the difference!) is waiting for me at acclaimed playwright and director Mahesh Dattani’s Marine Drive home. He answers the door himself, the whiff of freshly-made tea instantly warming us into a conversation that ranges from some highly complex issues to our shared love for South Bombay. Punctuated with generous doses of laughter, here’s someone who takes his writing seriously but himself, not so much. To his benefit, it adds a wholly different layer to a person who has the image of being incredibly intense. Given the kind of thought-provoking, serious stories he has written for theatre or cinema, that’s really no surprise. Then somewhere in the conversation he adds that he spent his birthday in the United States watching Mission: Impossible — Fallout, and you realise that one of the most profound storytellers of our time also has guilty pleasures. There is some balance in the universe after all. Final Solutions Not always does the onus of maintaining the balance remain on oneself. Dattani spent two years from 1990 writing a play that found much of its inspiration from the Ahmedabad riots between Hindus and Muslims in the years prior. What he hadn’t accounted for while being deep into the rehearsal stages was that the Babri Masjid would be demolished in December 1992. The play was scheduled to be staged a few weeks later, but sponsors withdrew. “Final Solutions was a play about tolerance and I felt that the play ought to be staged then despite the circumstances. In fact, it was possibly even more imperative to do so. Understandably, the circumstances meant that the sponsors pulled out. It was a sensitive time. The commissioner of police in Bangalore had advised me to hold on for a while. Then the Bombay riots of January 1993 happened. Alyque Padamsee had commissioned this play and unfortunately found himself in a pickle where some things he had said had ruffled some feathers with the VHP. He had to make a personal apology and so again, the time wasn’t right to stage it,” Dattani recounts. [caption id=“attachment_5097801” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Mahesh Dattani. Image courtesy: Rahul Valmiki[/caption] Despite his vulnerability, though, Padamsee was keen to stage the play. When he watched Madhyam’s (a Bangalore-based NGO working with marginal voices) production of it in Bangalore, he knew he had to bring it to Mumbai. When he announced it, his sponsors backed out. “Here was the king of advertising with all these companies and brands working with him. They all said sorry and backed out. He put in his personal funds to bring this story to the stage. I drew immense courage from him and his ability to take a stand despite all odds. I wasn’t a very courageous person then but Alyque gave me the strength to stick to my convictions.” The play won Dattani the Sahitya Akademi award, making him the first Indian playwright in English to have received this honour. That Final Solutions is now studied in international universities is a testimony to the far-reaching nature of its content, but also to a deeply impactful style of writing. The process of researching the play involved meeting riot survivors in Gujarat and Karnataka, as well as talking to people who have grown up in mixed neighbourhoods, an experience that wasn’t always comfortable. “Never once did I feel the need to alter the writing. Alyque was very firm that if you have something to say, just say it. I was very clear that I wasn’t going to pussyfoot around. Yes, there were scenes that were sensitive, and they could be taken out of context. But the play is really about understanding the other and overcoming one’s demons,” Dattani says. Revisiting a play over 25 years since writing it often takes a playwright through a range of emotions — from pride at the writing to a feeling of irrelevance. A lot would have changed in context and the style of writing, one would imagine. Sure, they have, admits Dattani, “I did a production for camera recently and I was shocked at how relevant it is. Things have, in fact, gotten so much worse. What inspired me to write Final Solutions was the rise of the right-wing ideology in volatile Ahmedabad of the pre-1990s. It has gotten so much worse today.” Would he still be able to write the play in the India of today? “Yes, I wouldn’t think twice about it. Not because I have courage; I would be scared for my life, and of the consequences of writing the play. But there’s another voice in me that says I’d be terribly unhappy if I didn’t write it. So, if the choice is between being scared and being unhappy, I’d rather be scared,” he says, lament writ large in his face. Writing Process The context and content of the play aside, examining it purely from the writing perspective, Dattani feels he wouldn’t change it, “In terms of technique, I had a fairly good command over structure and the craft of writing. Things have changed now, and craft is a bit more fluid in writing, but I don’t want to succumb to fashions and trends. It is what it is. There is a certain design to it which is very 90s drama. I wouldn’t want to make it more contemporary. There are some passages when I read that make me feel quite proud of my own work.” Dattani believes that writing, while being an outlet for a writer, is not the product of one’s need to decompress. “I’m not saying ‘it’s an outlet and so I need to write’. I write because I need to write. That’s who you are… you need the writing to complete you. The gift is not the output, the gift is really the sensitivity you have to let it come to the fore.” Easy as it may sound, the process is far from it. He agrees that there may be an ease of writing, but it almost never comes easily. The writing process is a rather organic one; one needs to allow the writing to happen. A bigger self of you, not the smaller intellectual or self-identified self, needs to come to the fore. All good writing transcends the smaller self. “There’s a lot of thought and meditation and preparation and waiting that has gone into that moment that makes the writing come with ease. If I’m not in the mood or the right frame of mind, or if I haven’t thought it through in my head — not just intellectually, but if I’m not feeling it — it’s not going to happen. You could spend a whole day doing nothing, enjoying your space to just get to that moment of writing… it is all a part of the preparation for the actual writing. There’s the danger of the writing coming from your intellect, in a very controlled, intelligent, rational sort of way. That’s what you need for editing, not for writing. You need to distance from that to write. The first draft needs preparation and passion.” [caption id=“attachment_5097811” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Dattani at his residence. Image courtesy: Rahul Valmiki[/caption] 30 Days in September He put his entire life’s savings into a house in Madh Island where the sea and the silence inspire him to write. He spends his weekends at his Marine Drive residence, while reserving the weekdays for his writing. The sea inspires Dattani, giving him a sense of calm, a sanctuary from the din of the city and an imagery of depth and possibilities. But even for someone who consciously decompresses, Dattani hasn’t always found his usual suspects coming in handy during the writing process. For the first time ever, he made a change in his writing environment while working on 30 Days in September. Commissioned by the NGO Rahi that works with victims of incest, Dattani maintains this was his most difficult play to write. “I almost abandoned writing the play, even before a word was written. I had the testimonies of six survivors who had been through the process of therapy and rehabilitation. They were okay to talk about it, but I don’t think I was ready to receive it. I had the audio tapes with hours of recordings of them talking. I just couldn’t muster the courage to listen to them again and again as part of the research.” Dattani spoke with a friend in Nrityagram, the modern gurukul set up by the late Protima Gauri, and moved there to be among happy, empowered women. Far from being a clash in imagery, this contrasting scene to his writing gave him the calm he needed to address difficult topics such as child sexual abuse and incest. “I wrote this play on the verandah in Nrityagram, listening to the dance of these wonderful women. They were staying here on their own volition, making their own rules, growing their own vegetables, cooking and being deeply involved in their own arts and crafts. I realised I needed these happy women and their positive energy to keep recharging myself through the writing of the play. I wanted reassurance that all is right in the world despite writing about something so excruciating.” People have cried after watching the play, some have questioned why he had to make it such a painful watch, some others have been rendered numb post the performance; all are reactions that Dattani receives positively. “This is the power of theatre. It’s about telling your story while you don’t need to do so yourself, because it’s either too painful or you’re not aware of it. You’re trained to disregard your instinct, tell yourself it’s not important but it festers. Theatre makes you remember, because if you don’t remember, how are you going to heal?” If the healing for the audience lies with the experience of the play, the writer has to find his own way to recuperate because the process of writing the play need not always rejuvenate him/her. “In a way, as a creative writer when you prepare, you are imbibing a lot of your characters, vicariously living their lives. For a creative writer, everything is also personal. It is about your own person. If it isn’t me, I can’t write it. Some people can simplistically understand it as being something that happened in my life, but that’s not true. For something to be personal to you, it need not have actually happened to you. Sexual abuse is a deeply political subject, one which is least discussed in our country. And theatre always works in the realm of the personal.” For someone who has had commercial successes with plays like Dance Like A Man, Dattani considers 30 Days in September the play of which he’s most proud. “It’s like climbing a mountain. You feel so accomplished after you’ve overcome all these obstacles, and more importantly, your own weaknesses.”

Revisiting a play over 25 years since writing it often takes a playwright through a range of emotions — from pride at the writing to a feeling of irrelevance. A lot has changed in context and the style of writing, Dattani admits.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)