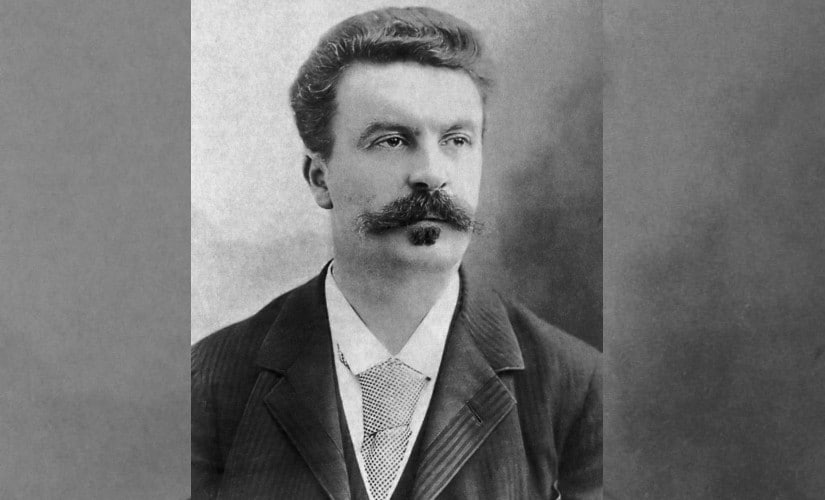

In this monthly column, Jai Arjun Singh scours through his bookshelves to pick out titles that have impacted him at various times in his life. Opening a new anthology the other day, The Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction, I found myself reflexively following a ritual developed in childhood. I looked at the page numbers listed on the Contents page, homed in on the shortest stories, and picked one. After finishing the story, I put a little dot next to the title, as a reminder that I had read it (this is especially useful if the anthology is a fat one), before moving on to the next, slightly longer story. I have dozens of thick books filled with those little dots. A time-lapse video depiction of my encounters with Contents pages over the decades might begin with a close-up of a child’s hand awkwardly marking a story title with a pencil, then dissolve into a shot of an adult hand, this time holding a pen, doing the same thing on the page of a more grown-up-looking book. Such anthologies – short-story collections, organised by genre or author – were a big part of my teenage reading life. They helped me discover some favourite writers, including Roald Dahl, Damon Runyon, Saki… and Guy de Maupassant, a collection of whose short fiction became – very improbably – a treasured book. I don’t remember how I stumbled upon Maupassant, but I remember the little thrill I felt when an acquaintance who knew a bit of French saw my book and, sotto voce, let me into a secret that I could impress friends and family with: the ‘Guy’ was pronounced ‘Gee’ with a soft G. I still have the simple-looking anthology, which was priced at just Rs 125 (in 1991). The printing and binding standards aren’t great, but it has held together. No translator’s name is mentioned anywhere in this book. And the cover, while it may have been apposite to some of Maupassant’s stories, seems like it was there purely to tantalise the casual browser: a young woman holding up a cloth in front of her, her bare back turned towards the reader. Having become a cinephile around the same time (and watching films I was too young to watch), I thought this woman looked a little like the beautiful French actress Catherine Deneuve in one of the steamier scenes from Belle du Jour. [caption id=“attachment_6345621” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Guy de Maupassant. Wikimedia Commons[/caption] Much as I enjoyed this book, it was a daunting beast – more than a thousand pages in very small font – and looking at the little dots on the Contents pages now, I find that I have read only around half of the 200-plus stories in it. So I won’t make any grand statements about Maupassant’s body of work.

What I do remember is that for me, much of his writing was “adult” in ways that had little to do with sexually explicit content. It opened a window of insight into the mysteries of adult behaviour, and examined ideas and conflicts I had no firsthand experience of, at the time.

Two stories in particular stuck with me, creating associations that I couldn’t have articulated as an adolescent, but which I understand better now. The first, a reflection on how the human mind moves constantly between rationality and irrational dread, was Beside a Dead Man, in which two men are tasked with spending the night alongside the dead body of the philosopher Schopenhauer. Unpleasant as this vigil is, it is made more so by the fact that the deceased had “a frightful smile” even in life; as the night wears on, the men are terrified by the sense of an “immaterial essence” – a soul, or something scarier? – persisting after death. Then they catch a glimpse of something white flying out of the corpse and through the air, and notice that his grin has become even more macabre than before. The story ends in an offhand manner, with a non-supernatural explanation, but that almost doesn’t matter; so tangible is the sense of fear and claustrophobia that has been created along the way.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)