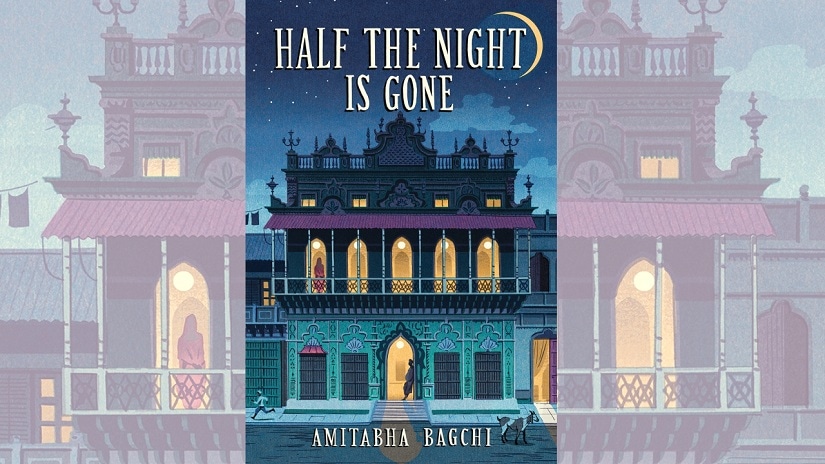

Introduction: ‘Half the Night is Gone’ is Amitabha Bagchi’s latest novel, published by Juggernaut Books. Set in early 20th century Old Delhi, ‘Half the Night is Gone’ tells the story of a celebrated Hindi novelist Vishwanath, heartbroken by the recent loss of his son. The tragedy spurs him to write a tale about the wealthy Lala Motichand and his three sons: the self-confident Dinanath, the true heir to Motichand’s mercantile temperament; lonely Diwanchand, uninterested in business and steeped in poetry; and illegitimate Makhan Lal, a Marx-loving schoolteacher kept to the periphery of his father’s life. By writing about mortality and family, Vishwanath confronts the wreckage of his own life while seeking to make sense of the new India that came into being after independence. *** For the first time in the year-and-a-half she had spent in Delhi, Kamala gained entrance to Suvarnalata’s boudoir, a lavishly appointed room organised around a large four-poster bed whose polished wood left no doubts in anyone’s mind as to the primary role it played in establishing the status of the room’s resident as a woman in current possession of a fulsome married life. And if there was any doubt left in the mind of the jealous it was fully extinguished by the presence of a large standing mirror that stood to one side, doubling the depth of the already massive room, in front of a table overflowing with small and large bottles and implements whose sole purpose was the beautification of the woman who had acquired them. Standing in this room looking at her childhood friend, who sat on a brocaded chaise longue bent over her silver paan box, Kamala thought of how easily their positions could have been reversed and, immediately, felt a sense of relief, and gratitude, that it was not so. When Suvarnalata finally gathered the courage to look up she found, to her surprise, that Kamala looked different from how she had remembered her although it had only been six or seven months since she had last seen her, and even then she had only seen her sidelong in the midst of hectic wedding preparations. It had, she realised, been almost a year since she had looked properly at her friend. She had become thinner, the softness of her face had vanished, but, standing upright in a manner that lacked arrogance, she appeared to be at ease. Her face was effulgent, the source of light being her eyes that were lucent, not with sadness or happiness, but something else, something undefinably greater and deeper, the sight of which, despite herself and despite the purpose of this meeting, elicited a kind of reverence from Suvarnalata. ‘How are you?’ Suvarnalata asked, not knowing what else to say. [caption id=“attachment_4664101” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Cover for Amitabha Bagchi’s Half The Night Is Gone, published by Juggernaut Books[/caption] ‘I am okay,’ said Kamala, so still that it appeared as if even her lips did not move when she spoke. ‘What did you call me here for?’ Realising that she had not thought through how she would say what she wanted to say to Kamala, and that, even if she had, it would not be possible to couch what she wanted to say in any terms that would make it appear like anything but what it was, Suvarnalata said, ‘I want you to leave. My uncle often donates money to an ashram in Vrindavan. I have written to him and he has made the arrangements. I will send someone with you to settle you in there.’ ‘No,’ said Kamala, and turned to leave. ‘No?’ ‘No.’ ‘What do you want?’ asked Suvarnalata. ‘I don’t want anything,’ Kamala said. ‘Then why won’t you leave?’ ‘Because Radha doesn’t leave Vrindavan,’ said Kamala. ‘Only Krishna does.’ ‘You are not Radha,’ said Suvarnalata sharply, ‘and he is not your Krishna.’ ‘And now that chhoti bahu is here,’ said Kamala, her voice quavering with anger, ‘you are not Rukmini any more.’ Suvarnalata’s body went limp as she watched Kamala walk away, then, once Kamala had left the room, it seized up again and she began to weep uncontrollably for her friend and for the childhood she had shared with her, both of which were now gone for good. Later that night Kamala’s pride assailed her: how could she have refused to leave when the person who had invited her here had asked her to go? What was there for her in this place anyway? If it was one meal a day, a roof over her head and meaningless chatter till she died that she wanted, Vrindavan was as good as any other place. Was it because she knew that Suvarnalata was worried about her presence here, worried the new wife would find out that her bhabhi’s friend was known by all and sundry to have fallen in love with Diwanchand? Was it because when Shakuntala came to the ashram for this katha that had suddenly been announced after almost a year’s hiatus she would find out and she would blame Suvarnalata for endangering her marriage? Was that what she wanted: to take revenge on her friend by refusing to conveniently disappear before chhoti bahu saw her and realised that something had been hidden from her. But what had been hidden from her? Nothing! Just that some foolish widow fell in love with her husband, even though the husband did nothing to ever show that he reciprocated that love or even noticed that this foolish widow was in love. But why, why had she fallen in love with him in the first place? What was it? Was it his face, his beautiful face with its high forehead partly covered by a lock of hair, and his cloudy, sad eyes? Or was it the way he spoke, tentatively, in a sweet voice that was still the voice of a man, virile yet soft? And the things he said! The way he loved his Ram! The way he swayed with Tulsi, the way he pronounced each word, each verse, as if he was trying to create music, trying to build a house of sound, a house that was one moment a cosy cottage in a verdant wood and one moment a magnificent palace on a vast plain with balustraded staircases coming down its front, a house that was ephemeral in nature but comforting, a house where she felt she could find repose because it was a house in which she knew he found repose. Knowing that he could never be hers, how foolish was it of her to let herself fall in love with him! It was all very well to say, ‘I did not will it to happen’ or even to say, ‘I did not want it to happen’, but why did she not prevent it from happening? Why? Why put herself through all this pain? All these months, a year now, every time she thought she had quelled the feeling, something would happen to make it come alive again — the laburnum burst of summer, so bright that it seemed the tree was trying to talk back to the May sun, the first rain of the season drawing fragrance out of the earth, fragrance that quickened every heart that was not yet dead, large, dark clouds flying across the monsoon sky like gopis running to the river at the sound of the flute, then the delicate but moist coolness of October with its scented mornings, the pale sun’s warmth at the height of winter, and then, finally, unbearably, spring resplendent with colours, each flower like a sharp dart thrown at her heart — and again she would find herself exulting in the sense of him who had stolen her heart, and feeling that she wanted nothing more: not his touch, because the touch of the breeze on her face was his touch, not his voice because the koel sang in the morning in his voice, not his kisses because jasmine petals felt like his lips on her lips, their fragrance sending her into throes of exaltation so that all she could hear was his name and all she could see was his face. And with that sublime face in her eyes and that mellifluous name in her ears, Kamala floated away into a deep and dreamless sleep.

Set in early 20th century Old Delhi, ‘Half the Night is Gone’ tells the story of a celebrated Hindi novelist Vishwanath, heartbroken by the recent loss of his son. The tragedy spurs him to write a tale.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)