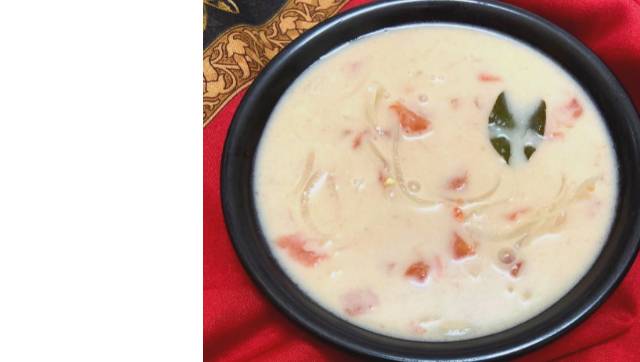

This is the final instalment of a three-part Indian food history series that delves into time-tested culinary techniques and single-ingredient origins and showcases how some of these practices have been reflected across states and communities. Each installation of this series will focus on a specific flavour profile; part 3 focuses on ’tart’. Read part 1 here , and 2 here . *** “My Odia grandmother called tomatoes bilayti baigana (foreign eggplant) until her dying day — after living more than a hundred years at the end of the 20th century.” Behind this intriguing revelation from Krishnendu Ray, chair of New York University’s Department of Nutrition and Food Studies, lies the story of a complex fruit that may never quite have shrugged off its alien status and novelty for not only his grandmother but also the regional Indian cuisines into which it made tentative inroads. With their unfamiliar nature and attributes, tomatoes, it seemed, had this ability to stump right from their initial days of inception in the Mughal kitchens as is evident from early mentions in Indo-Persian cookbooks such as the Nusḵẖa-i Niʿmat Ḵẖān (1801). While the credibility of using these culinary manuals as sources is often discounted, with only the names of scribes and date of transliteration offered and the name of the author often missing, Divya Narayanan, in her academic works, makes a case for them lending utilitarian value while acquainting an Indian audience with European foods. In the Nusḵẖa-i Niʿmat Ḵẖān, for example, the use of the New World imports is enlisted in a tomato soup referred to as the tarkīb-i ṭomāṭā sūp yaʿnī shorbā wilāyatī baigan, literally translating to “recipe for tomato soup otherwise known as wilāyatī baigan”. Of most interest, however, is the recipe description, which is consistent in its reference to the fruit as “baigan” or eggplant, thus offering etymological insights into the prevailing practice of naming a novel fruit or vegetable after something known, thereby lending the unfamiliar an air of familiarity. The tomato’s offshore point of origin is highlighted through the very name wilāyatī baigan or ‘foreign eggplant’ while more layered insights come by way of it being alluded to by both its transliterated English name and Indian or Persian name, suggesting that while it was still an uncommon ingredient, it was beginning to receive attention from the nobility. Botanically classified as berries, widely recognised as a fruit, and commonly used as a “culinary vegetable”, it seems only natural that tomatoes, with a sugar content that is significantly lower than that associated with “culinary fruit”, have often been the subject of contention. Their ambiguous status even invited legal dispute in the United States in 1887 as US tariff laws imposed a duty on vegetables but not fruit. The unique conundrum tomatoes posed as they first crept into the Indian context could, according to food writer Vikram Doctor, be attributed to the fact that they, “looked like fruit but were not sweet. They have a strong umami effect, which comes into play when you cook them down to a concentrated form.” He adds that this could also be why tomatoes were propagated by Mughal cuisine seeing as they, “cooked onions and tomatoes down to a thick base”. Ray brings another observation to light, which is key in understanding the Indian integration of tomatoes into diets. “I think compared to nouvelle cuisine, the Indian palate does not appreciate a thing in itself. It has to be layered into complex aromatics. We went in the opposite direction to the French-Italian palate after around ca 1800.” This bifurcation, according to Ray, was “the great divergence”. The Indian treatment of the tomato, thereby, results in it seldom being celebrated as the solitary or star ingredient of a dish, instead being relied on to hold fort with the onion-ginger-garlic trinity and lend a sauce-like quality and tartness to curries. It is an integral component of North Indian “mother” gravies such as the lababdar — a chunky brown onion and tomato gravy — where equal parts of chopped onions and tomatoes act as the base to any manner of vegetable or protein. The butter-rich makhni gravy (of murgh makhni and paneer makhni fame) is perhaps one of the best-loved avatars of tomato-based curries. When asked whether tomatoes are championed in a raw or minimally cooked format in Odia cuisine, Ray inadvertently touches upon the relevance of anthropologist Sidney Mintz’s core-fringe-legume pattern theory. Tomatoes, he says, are almost never uncooked but steamed then peeled and drizzled with pungent mustard oil, raw onions, green chillies and salt and, “maybe a little sugar to slurp up with steamed rice as a chutney”. In a nod to Mintz’s framework, he goes on to dub them, “a stimulating fringe that allows the carbohydrate to go down smoothly”. In his paper Food Patterns in Agrarian Societies: The “Core-Fringe-Legume Hypothesis” A Dialogue, Mintz argued that in large, old, agrarian societies, meals commonly consisted of a starchy “core,” which was complemented by a “fringe” of foods. It was this “fringe”, according to him, which consisted of substances that made the “core” more palatable. [caption id=“attachment_9640031” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Tomato Gawd Lonchè. Photo © Swapneel Prabhu[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_9640051” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Tomato Sasam. Photo © Swapneel Prabhu[/caption] Ray reiterates the importance of Mintz’s discourse when he says, “Every cuisine in the world had it as their central principle prior to the modern era.” If one were to apply Mintz’s logic to tomatoes as a fringe, their appeal would appear, on the surface, to be immense given that they have the requisite “enlivening” attributes he touches upon. However, the reluctant and often highly specific dish-based absorption of tomatoes as a standalone ingredient, fringe or even souring agent by several communities and regions in India tells a different story. In 1832, mentions of the tomato’s common usage across the subcontinent were recorded in the Flora Indica by Scottish botanist William Roxburgh (known as the founding father of Indian botany). While Portuguese explorers were generally accepted to have introduced the fruit to Indian shores, its widespread cultivation was credited to the British. Citations in Sir George Christopher Molesworth Birdwood’s Catalogue of the Vegetable Productions of the Presidency of Bombay (1865) may well have illustrated the presence of tomatoes in sauces and salads, but it was JF Duthie and JB Fuller’s Field and Garden Crops of the North-Western Provinces and Oudh (1882-1893), which mentioned how the Indian palate was gradually being eased into its relationship with the tomato on account of its acidity. George Watt’s A Dictionary of the Economic Products of India confirmed that, “natives are beginning to appreciate the fruit, but the plant is still chiefly cultivated for the European population.” The Bengalis and Burmans, according to Watts, were beginning to use it in their sour curries. While the tart properties of tomatoes should have naturally lent themselves to being adopted as a souring agent of preference, Doctor reminds us of the hyperlocal range of options, such as tamarind; kokum; anardhana (pomegranate seeds); and the dried fruit of monkey jackfruit, which were often a better fit for the existing ingredient pool, thereby standing in the way of a large-scale conversion. Founder of restaurant Maiyam Past Foods Vijhay Ganesh M points out that long before tomatoes made an appearance, one of the earliest souring agents in South Indian states such as Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh was fermented rice starch, which was used as a base for fish curries, vatha kuzhambu and kaazha kuzhambu. This was gradually replaced by tamarind. Home chef and content creator Swapneel Prabhu is a member of the Saraswat community who, he says, can trace their origins back to the Kashmir valley. Fearing persecution, they fled eastward towards Bengal, which was known as the Goud region and then moved down south to the western coast, where they settled in Goa and further down the coast in northern and coastal Karnataka. The maternal side of his family belongs to the Chitrapur Saraswat subsect while his paternal lineage is of the Goud subsect, resulting in “an eclectic confluence of culture and cuisine at home”. [caption id=“attachment_9640061” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Prawn Qorma. Photo © Saher Khanzada, founder, The Bombay Glutton Blog*[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_9640071” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Ukaar. Photo © Saher Khanzada, founder, The Bombay Glutton Blog*[/caption] Upon reflection, Prabhu adds, “If I look at our cuisine closely, tamarind has always been the preferred souring agent. Tomatoes are relatively new and only a handful of recipes, such as the sasam, feature them as the main component.” He elucidates that the word sasam is a derivative of the Konkani word for mustard seeds and is also used to refer to a specific accompaniment. While some sasams are curd-based, others are cooked. The tomato sasam, according to Prabhu, may also have been an interesting act of ingenuity, born out of the need to adapt, for women such as his grandmother and others, “who moved out of the region and didn’t have access to community-specific produce.” Looking back, Prabhu, realises how it “fit right into the scheme of things”, owing to its acidic properties, which countered the base of raw mustard seeds ground with coconut and red chillies. Prabhu lists the tomato gawd lonchè as the other distinct tomato recipe in the Saraswat repertoire. Tomatoes serve as the perfect stand-in ingredient for the seasonal raw mangoes that the original recipe calls for, ensuring that a version of the sweet and savoury instant pickle can be relished year-round. The reliance on tomatoes, it seems safe to say, remains skin-deep for the Saraswats and the community’s real foolproof “trinity”, according to Prabhu, is tamarind, coconut and bydagi chillies. He adds that elaborate meals can be prepared, “without touching ginger, garlic and tomatoes”. A staunch loyalty towards souring agents seems to accompany the nuanced territory of micro-cuisines, and we are reminded of the lukewarm reception to tomatoes by coastal communities such as the Kokani Muslims who inhabit the country’s west coast by Saher Khanzada, founder of The Bombay Glutton blog. Limited access to them also stood as a barrier and Khanzada states that, “tomatoes are not even considered a souring agent, we use tamarind, amboshi and kokum, and some parts of Thane and Palghar use a wild berry called karandi in their fish curries”. Although restricted in their use, Khanzada highlights two classic dishes, which reflect a later availability of tomatoes. While the coconut-based stew ukaar is laced with tomatoes and onions and serves as the perfect mellow accompaniment to kolam rice, Khanzada points out that tomatoes aren’t indispensable and a variation of the dish can be made with raw mangoes and kokum. She adds that the prawn qorma is another rare example of a seafood curry that uses onions and tomatoes, unlike its more traditional atavni and haldavni counterparts. The tomato has had a history of being subjected to censure and suspicion. The French referred to it as the pommes d’amour or the love apple and the Germans as the Apple of Paradise. While the English were besotted by its bold, red hue, the fruit didn’t immediately receive a clean chit on account of its leaves bearing a resemblance to the poisonous Deadly Nightshade. On being asked whether the foreignness of the “foreign eggplant”, stood in the way of its thorough and complete absorption into regional Indian cuisines, Ray says, “I think its foreignness was both a hindrance and an enticement. The tomato was seen as being too seductive and sensual in its voluptuous redness — it looked too good to be real or good for you.” *** Jehan Nizar is an independent features writer and food blogger based in Chennai, India. Her work most often explores food as a point of convergence for history and anthropology and has appeared in national and international publications such as The Wire, The Wire Science, Firstpost, Verve Magazine, Whetstone Magazine, PEN America, The Spruce Eats and Gulf News. She formerly wrote a weekly food column for Asiaville. * Images © Saher Khanzada by special arrangement, for one-time editorial use.

With their unfamiliar attributes, tomatoes, it seemed, had an ability to stump right from their initial days of inception in the Mughal kitchens as is evident from early mentions in Indo-Persian cookbooks such as the Nusḵẖa-i Niʿmat Ḵẖān, where it is referred to as the wilāyatī baigan or foreign eggplant.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)