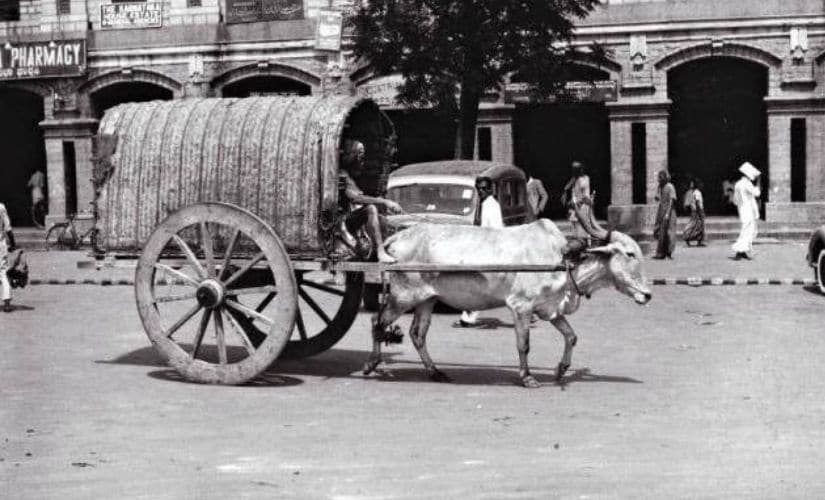

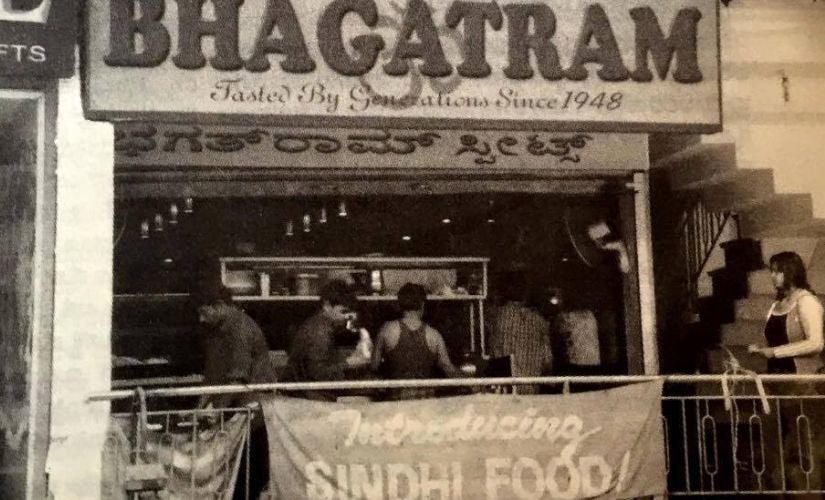

Kempe Gowda, a feudatory ruler in the Vijayanagara empire, had laid the foundation for modern-day Bengaluru or Bangalore — a new township high up on the Deccan Plateau, in 1537. Little did he envision the mammoth size it would attain only centuries down the line, providing homes to millions from all over the country and world. That people seeking a livelihood, refuge, and a peaceful place to live in would all flock to his city — now teetering on the edge of a staggering count of 12 million — may have been a tad difficult for him to foresee. However, as history suggests, Kempe Gowda’s vision for his beloved Bangalore was nothing short of big. He planned and built a proper township with a fort, temples, gardens, water tanks, market places and housing blocks. The area he chose for this, although thickly forested, was already populated not just with forest-dwelling tribes, but with native Kannadigas, and Telugu and Tamil migrants as well. The construction of the township further attracted more people from faraway lands, mostly traders and artisans in search of a livelihood. The Deccan Plateau has conventionally been a haven for various types of immigrants. People fleeing religious persecution sought sojourn here, so did soldiers ejected from defeated armies, in search of a place to live. While craftsmen from distant lands built monuments in Bangalore, artists and musicians invited by royal families decided to stay back. The government even created a settlement at Bylakuppa for Tibetan refugees, when they fled their homeland to follow the Dalai Lama. [caption id=“attachment_7052411” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  A street in Bangalore. Facebook/Old Bangalore.[/caption] My own ancestors were Tamil speaking migrants from Tanjore, who came to Bangalore in the 12th century. They followed Swami Ramanuja, who was escaping religious persecution in his own home town. The big group of followers who came with him settled down near Mysore and became agriculturists. Ramanuja, who preached a casteless form of Vaishnavism, is said to have converted the Jain king, Vishnu Vardhana, who ruled then. Clearly, Jainism was brought to the region by immigrants sometime around the third century BC. A group of Jains fleeing from famine in north India settled in the Chandragiri Hills. The community, which continues to flourish in Karnataka, has made its mark through architectural marvels of enormous rock-cut statues and temples. The Kodavas of Coorg trace their ancestry to Alexander’s soldiers, who fled to south India after he died, leaving them abandoned. The Bangalore township itself went through several transitions. After Kempe Gowda, many ruling dynasties came and went. The conquerors always brought with them their own followers and settlers. In the 17th century, Maratha warrior Shivaji’s father Shahaji ruled over Bangalore. Born to Shahaji’s first wife Jijabai, Shivaji came to Bangalore with his mother when he was 12, and got married here. He lived in the city with his brother for a couple of years before returning to Maharashtra. Even today, there is a sizeable population of Maharashtrians in the city who have blended in almost seamlessly with the local Kannadigas. A major locality in Bangalore, known as Shivaji Nagar, is now a commercial hub mostly inhabited by Muslims. Moreover, a handful of Shivaji statues function as landmarks in the city. [caption id=“attachment_7052121” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Bull Temple Road, Bangalore. Facebook/Old Bangalore.[/caption] On the other hand, the British were also making their presence felt in the area around late 19th century. They had established the Kolar gold mines, just 60 miles away from Bangalore, where miners from all over the world found employment. English, Italian and Irish miners worked together with Tamil and Telugu speaking men from neighbouring areas in these quarries. Eventually, these foreigners married local women, and settled down here with their families. In 1882, Chamaraja Wadiyar IX, the Maharaja of Mysore, granted 3,900 acres of land to the Eurasian and Anglo-Indian Association for establishing agricultural settlements in Bangalore’s Whitefield area. This beautiful, fertile tract of land lay on the Eastern periphery of the city, and soon, it became a quaint little township unto itself, with colonial-style bungalows and gardens. In 1907, the neighbourhood had less than 50 houses, about 2,000 acres of farmland, and 130 residents. The famous Waverly Inn, which has now ceased to exist, is where people visiting Whitefield would stay, and the only way to reach it from the railway station was by bullock carts. The bullock cart ride, costing eight annas at the time, could only be arranged by the wife of the inn-keeper, who would have to be written to in advance before a guest arrived. The next big influx of migrants was in the 1940s, when the British built a large cantonment in Bangalore, for housing soldiers recuperating from wars. A large number of people were attracted to the cantonment while looking for work, trade, treatment for injured army-men, constructing houses, hospitals and recreational facilities. [caption id=“attachment_7052141” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Old modes of transport in Bangalore. Facebook/Old Bangalore.[/caption] Owing to the large and all-encompassing British presence, Bangalore soon earned the moniker of ‘The Little England’. With the British laying down their roots here, a sizeable community of Anglo-Indians began to grow. In the 1940s, at the cusp of the Second World War, the Anglo-Indians in Bangalore attained their cultural and social zenith. The British built many beautiful churches that still dot the Cantonment area, along with ballrooms, film-theatres, and sprawling colonial-style houses with big gardens. When the British finally left by the 1950s, the city had a beautifully diverse, yet well-integrated population, just shy of a million. It was a pretty little town with shaded avenues, large bungalows, and all the amenities of modern living. However, Bangalore’s most attractive feature was the ‘air-conditioned’ climate round the year, which attracted senior citizens looking for a comfortable place to settle in from all over the country. And so, Bangalore, as the British had named it, earned yet another enviable tag of being the “Pensioners’ Paradise”. It was also known as the “Garden City”, as the fertile soil and agreeable climate were conducive to gardening. Bangalore’s healthy air was proving to be infectious, as it attracted companies like HMT, BEL and ITI, who set up their manufacturing units here soon after. Additionally, scientific research centers came up around the Indian Institute of Science. By the 1970s, major research and development organisations, like ISRO, DRDO, and NAL had set up headquarters in Bangalore. This meant that scientists, engineers and academics from all over the country would eventually come and settle here as well. Families living in the colonies attached to the various institutions spoke different tongues, and the children grew up multilingual. [caption id=“attachment_7052161” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Famous Bhagatram Sweets in Bangalore. Facebook/Old Bangalore.[/caption] In the year 1970, Bangalore’s population touched 1.6 million, and signs of drastic change began to surface. With more people moving into the city, greater demand for housing emerged. Gradually, old houses with big gardens gave way to multi-storey buildings; the roads had more vehicles, and more importantly, real estate sharks began eyeing the drying beds of water bodies as potential sites for housing. Soon, many of the city’s famous lakes and tanks disappeared. Even the government was guilty of filling up a few big ones to create civic amenities. This, however, was followed by the next and perhaps the biggest phase of expansion experienced by Bangalore — the rise of the Silicon Valley. A boom in information technology turned Bangalore into India’s new industrial hub, morphing it into a literal replica of California in the USA. These changes had a long-term impact on the metropolis’ DNA. Money poured in, and so did waves of people from all over the country. In 1990, Bangalore’s population crossed 4 million; by the year 2000, it was over 5.5 million. [caption id=“attachment_7052191” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Bengaluru — from Garden City to Silicon Valley of India. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons.[/caption] Whitefield was no longer a quaint village, as most of its old inhabitants had migrated. The area was now a major technology hub, with giant concrete structures mushrooming all across a land once occupied by cosy bungalows. Despite the fact that it had now become a part of Bangalore city, Whitefield seemed farther than ever, as a traffic-ridden, two-hour-long drive stood in its way to the Central Business District. Other technology hubs, like Electronic City, also emerged and became equally inaccessible due to the impenetrable traffic. Old modes of transport, like bullock carts and horse-drawn jutkas, had already become things of the past. At this point in time, Bangalore witnessed a flourishing real estate, in order to cater to the influx of new inhabitants. Every inch of vacant land got occupied. More people poured in to build bigger structures. The Tamil construction workers were now joined by plumbers, electricians, and carpenters, who hailed from Odisha, Bihar, and other parts of India. With a steady flow of money into the city, Bangalore became an increasingly attractive employment hub and settlers’ town. Young people fleeing from political unrest and lack of good educational institutions in their own home-states also started migrating to Bangalore in large numbers. Educational institutions catering to foreign students multiplied rapidly, drawing students from Asian and African countries as well. In 2011, the population was circa 8 million; today, nearly 12 million live in Bengaluru — the leap in the figures proving its status as one of the fastest growing cities in the world, with a 38% increase in population between 1991 and 2001. [caption id=“attachment_7052201” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Bengaluru at night. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons.[/caption] Meanwhile, the city’s founding father, Kempe Gowda lay forgotten. No one knew where he was buried, until an amateur historian found his grave a couple of years ago. It lay in a neglected spot on the outskirts of the city, covered in shrubs and weeds. It has since been properly identified and resurrected. Lying deep underneath layers of concrete, if only Kempe Gowda could see the city he had founded as it is today.

Bangalore, or Bengaluru, a city of immigrants founded by Kempe Gowda, stands tall as one of India’s fastest growing metropolises, housing a whopping 12 million people on its gradually shrinking land. Here’s taking a closer look at how it went from being ‘Garden City’ to the Silicon Valley of India, in the matter of mere decades.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)