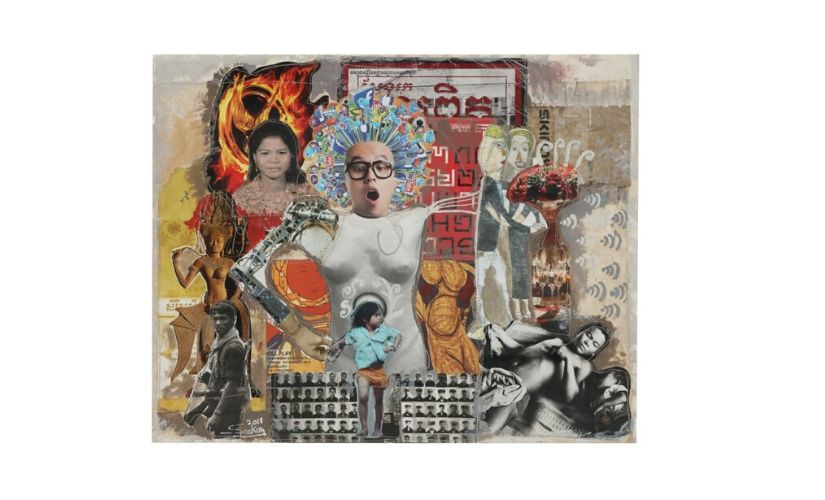

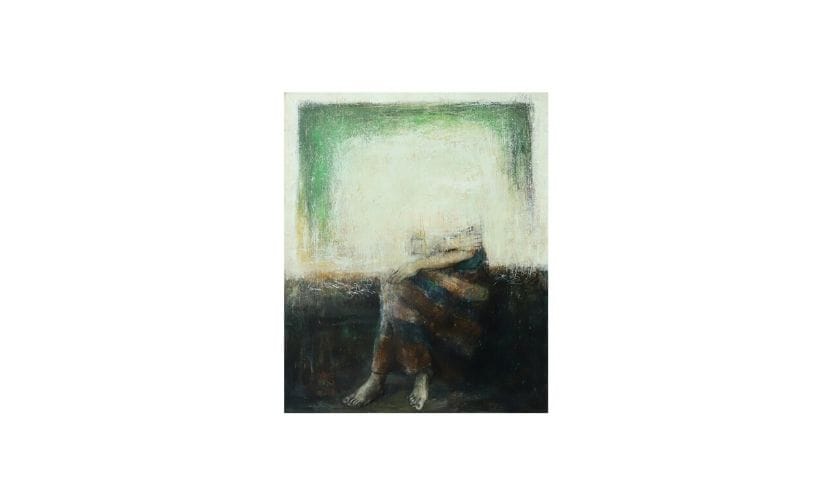

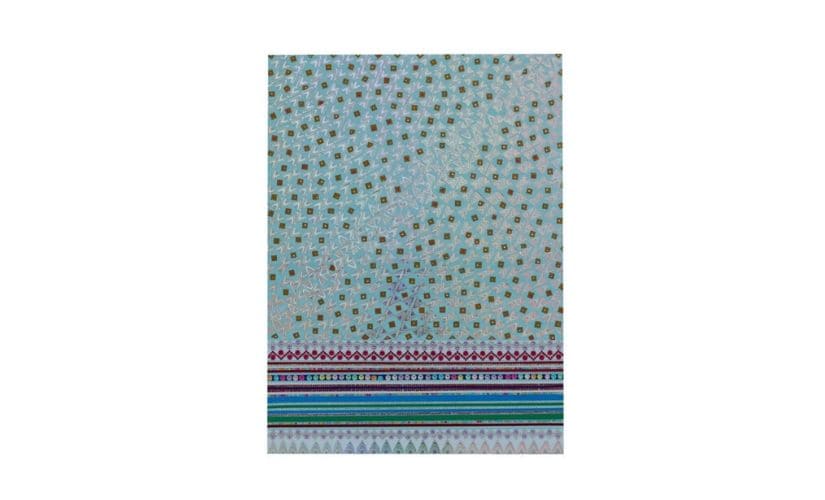

In the Indian art parlance, references to artists as ‘masters’ or ‘pioneering’ continue to enjoy wide currency, often implying a culture of exclusion against other artists from the so-called ’national canon’. But a new exhibition in the capital has interrogated this long-standing obsession with national artists that is, of course, not confined to India alone. The exhibition, recently mounted at Akar Prakar Contemporary, New Delhi, features works of 10 artists born in Cambodia, a country with a history of war, violence, and suppression of the arts. Curated by Phnom Penh-based Erin Gleeson, who is also a researcher of Southeast-Asian visual culture, the exhibition launches the ‘national’ debate right in its title: ‘Out of Line: Tracing Abstraction Within Contemporary Art in Cambodia’. In conversation with Firstpost, Gleeson talks about the dynamic elements at play in the exhibition, Khmer Rouge, and how history is veritably reflected in Cambodia’s art. The exhibition’s framework seeks to move away from dominant timelines (Western, for example) of art history, while pointing out that Cambodia has its own evolution of modern and contemporary art. In what way do artists in ‘Out of Line’ interrogate those timelines? There are different treatments of time in this show. Firstly, there is the curatorial embrace of multiple modernisms – that modernism happens at different times and looks at different ways per country or context. Scholarship on modern and contemporary art in Cambodia belongs largely to this century, so a lot of basics are being questioned. When was Cambodian modernism in art? When did ’the contemporary’ happen? Was there a sudden shift, and is there a clear delineation between the two? The exhibition converses with such questions of when and how the modern and the contemporary occurred and overlapped, and what art looked like and performed in the Cambodian context. These questions, by nature and circumstance, coincide with the increasing movement to decolonise art history – curators and art historians are interested in reconfiguring colonial notions of time and its narratives. [caption id=“attachment_7922801” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Curator Erin Gleeson[/caption] Could you illustrate this with an example of any recent scholarship on Cambodian art and history? During 2000-06, research by San Phalla, Preap Chanmara, Ingrid Muan and Ly Daravuth and others of the Reyum Institute of Art and Culture brought us documentation of 600 Buddhist temples across Cambodia in their book, Wat Painting in Cambodia, which can be activated by existing research by Ashley Thompson and current research by Vera Mey. For example, to point us to the fact that temple walls — from the early colonial 1900s to post-Independence 1960s — are a primary visual expression of modernism. The exhibition might say, no, abstraction in Cambodia is not isolated to the look and timeframe of Western modernism, but it also doesn’t define or isolate what abstraction is. Rather it brings together 10 artists, whose works have been named vernacularly as such by the artists themselves — by their desire and intention to be differently legible. Cambodia’s artists, art and its market suffered a great deal because of the death of a majority of its artists during the Khmer Rouge rule (1975-79). Was there a gap in art-making in Cambodia due to artists being either sent abroad to study art, or because they could not make much art, during the regime, that was outside of propaganda? How does the exhibition respond to this scenario? There have been so many major shifts in power and resulting ways of being an artist in and of ‘Cambodia,’ we cannot only start and end with the Khmer Rouge. If we think of the artists in the exhibition born between 1933-1990, every one of them was born into and touched by war. There was the unrest of colonisation when the territory was part of the French Protectorate’s Indochina (1887-1953), and within that the Franco-Thai War (1940-41) and Japanese occupation (1941-1945), then Cambodia as an independent nation (1954-1970), a US led-coup, bombing, and ensuing civil war (1970-1975), the genocide during Khmer Rouge rule (1975-1979) and the aftermath of ongoing conflict and refugee camps, Vietnam’s rule via People’s Republic of Kampuchea (1979-1989), and many more overlapping conflicts and details I have not named. [caption id=“attachment_7922811” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  ‘Pain Advanced Development’, by Leang Seckon[/caption] How did these periods affect the arts in Cambodia? The authoritarian nature of leadership resulted in sanctioning this or that kind of art and restricting others, whether explicitly or not. In general, there has been a reverence for the performing arts and artisanal practices that serve religious and political power, and belief. The late scholar Ingrid Muan’s research showed us that many artists worked for different regimes, thus shifted style and purpose. They might have trained under design professors, as part of the United States Information Service programs in the 1960s, then made propaganda posters for communist forces in the 1970s. After surviving the Khmer Rouge, they studied art in the former Soviet Bloc between the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, as part of a national effort to create leaders, after 90 per cent of artists were targeted and killed during the Khmer Rouge era. Many artists in the exhibition reject perpetuating iconographies drawn from Cambodian visual culture. What explains this opposition? The performing of narratives, choreographies, surface patterning, Hindu-Buddhist iconographies, et cetera, associated with the dominant ethnic identity “Khmer”, has been both a colonial and nationalising practice. For different reasons, many artists wish to engage with these histories – some by interacting with them, and some altogether dismissing and seeking other languages. We see Tith Kanitha creating abstract sculptures with utilitarian metal wire, and Yim Maline’s amorphous patterning on refuse. Both of these women’s practices are ways of processing their experiences of growing up in Cambodia’s culture, though their artworks purposely cannot be identified as such. Other artists, such as Than Sok, repurpose and reinvent ‘traditional’ iconographies, in many cases so that we can consider their relevance today. [caption id=“attachment_7922821” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  ‘Sitting’, by Nov Cheanick[/caption] Even though the exhibition traces forms of abstraction in Cambodian contemporary art, one of the most direct and powerful works in the exhibition is a video of Svay Sareth (b. 1972) eating rubber sandals at a village. Accompanying the video is a wall-based assemblage of black rubber sandals. What is the message behind his “absurd meal”? Svay Sareth’s video “I, Svay Sareth, eat rubber sandals” (2015) is in the gallery room, considering some examples of figurative abstraction. This self portrait is indeed direct – abstraction here is not visual, rather belongs to a kind of figurative code in the moving image that developed in contemporary art practices in Cambodia after 2010, in which artists performed futile acts in potent surroundings as a means of critique, oftentimes political. In Sareth’s case, he gnaws on and spits out rubber sandals that are highly symbolic of communist histories. This ‘meal’ is staged at an impoverished itinerant fishing village the artist finds comparable to the labour and refugee camps he survived for 17 years (1975-1992). [caption id=“attachment_7922831” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  ‘Sampot Civilisé City Girl’, by Chan Dany[/caption] From a political-artistic point of view, are there any specific works that influenced Sareth’s video? The work nods to two different works that Sareth notes as warnings against the capitalistic and consumer desire he sees depleting people, while ‘developing’ his country – a scene from Jorgen Leth’s ‘66 Scenes from America’, in which Andy Warhol indifferently consumes fast-food burger, and the scene when Charlie Chaplin prepares his boot for dinner as things go bust in Gold Rush. He was introduced to Chaplin’s work in the refugee camps, and notes the power of futility and humour in hopeless times. The video is positioned in conversation with the other works in the figurative room, that is Nov Cheanick’s obfuscation of identity in his portrait, Sitter, and Svay Ken and Sous Sodavy’s portraits of labourers. ‘Out of Line - Tracing Abstraction Within Contemporary Art in Cambodia’ was on view at Akar Prakar Contemporary, New Delhi, from 16 November, 2019 - 11 January, 2020.

‘Out of Line’, an exhibition curated in New Delhi by Phnom Pehn-based Erin Gleeson, explores a nation’s obsession with artists of ’national’ repute. It closely examines its relevance in Cambodia, a country with a history of war, violence, and suppression of the arts.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)