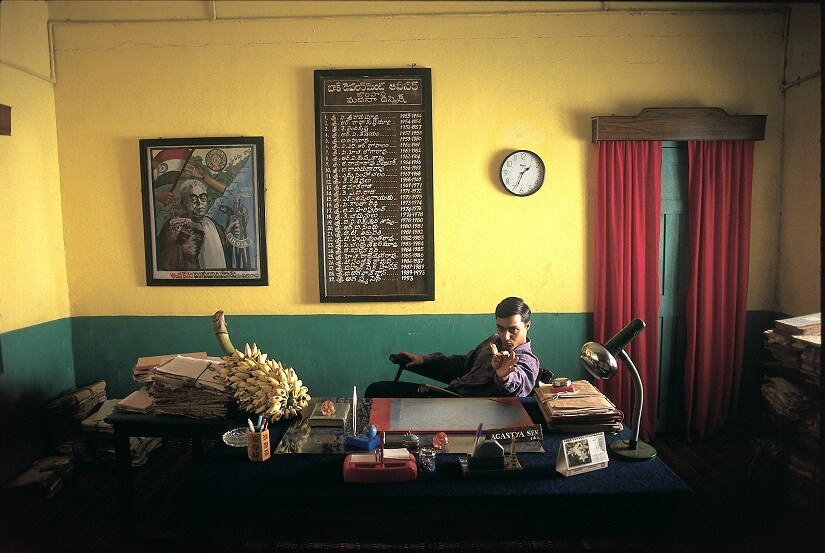

In the late 80s, India was a land parched not for a dearth of things to look at and moon over, but for sights to look away to. Communal riots, political upheavals, assassinations, a rejuvenated Bollywood and a potentially fabulous urban literary scene in the offing — it was all happening. You could, therefore, be forgiven if you assumed that the stories which were told were only the ones that mattered, and almost everyone—even the most cynical, lax men and women—was hurriedly rushing towards some purpose or a turn of measurable consequence. Idealism, which perhaps gave birth to the idea of photography itself, can lead to a circularly narrow view of the world, leaving the space at the margins empty. A space that Agastya Sen filled 30 years ago, when Upamanyu Chatterjee’s English, August was first published. [caption id=“attachment_4445457” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Upamanyu Chatterjee’s book was published after two years of continuous rejections by publishers[/caption] Agastya Sen, a 24-year-old officer in the Indian Administrative Service (IAS), is posted to remote Madna, a decrepit, sour-pit of a town unremarkable but for its people and the ‘hazaar fucked’ lives they lead. Sen, who is called August by his friends, carries his lazy urbanity with him, placing him at the edge of self-will, posturing but for the heck of it. In the midst of rustic outlets that connote Indianness for the outsider, Agastya seems tragicomically out of place. He quotes Marcus Aurelius and thinks of masturbating most of the time, but never actually does. In the many characters that find themselves in the pages of the book, a slack-jawed Sen looks for things to refer to memory. That in essence is English, August. Not a story, not a progression, but merely a straight walk through the hinterland with Agastya’s purposelessness and boredom hunched behind his eyes and years, insurmountably lulled by the prospect of a storm that he knows will never come. Chatterjee’s book was published after two years of continuous rejections by publishers. The ricochets did not stop there, as it took another 18 years before it was finally brought out in the US in 2006, which inevitably led to wider acclaim. In between, though, it had another intriguing story to tell. That of a National Award-winning film adaptation that now does not even exist. Dev Benegal read English, August several times before he knew he wanted to turn it into a film. “It struck home. I just could not see what others were talking about. I found it very funny and extremely moving. And on reading it, the plot was clear as daylight. And in hindsight, I learnt the most important lesson. Follow your instinct,” says Benegal, who is currently shooting his next feature in New York. But English, August was neither cinematic, nor a narrative that could be conditioned; so much so that the National Film Development Corporation (NDFC) rejected Benegal’s pitch by saying, ‘We’ve made this film many times before,’ referring essentially to the parallel cinema of the 70s and 80s. “I knew the film I did not want to make. I felt it would be dishonest and disingenuous to go make a film about people and worlds I did not know. I didn’t want to do anything that the ‘parallel cinema’ was doing at that time. I didn’t know the countryside the way Ray or Ghatak knew it. I was kicking against everything Indian cinema represented,” he says. [caption id=“attachment_4445467” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Rahul Bose in a still from English, August[/caption] Benegal made English, August in 1994, in the post-globalisation era where an English-speaking first-timer like Rahul Bose perfectly wore Agastya’s latitudinal conflicts, that hardly cut through him, but defined him nonetheless. “When I was casting I would close my eyes and listen to the actor speak the lines. I remember Bose was pretty upset about this and told Uma [da Cunha, the casting director], ‘He doesn’t even look at me.’ Agastya Sen had to sound right and that was absolutely important for me. Rahul got the state of Agastya right; his inner conflict. The ennui and sense of despair in the small town and the absurd situation of being a trainee,” Benegal says. English, August was of course one of those films that had to be made in the English. Slowly, after winning a National Award and recognition at festivals abroad, the film garnered a cult following. It was also a time of technical shifts. Digital was beaming in the market. English, August was also one of the first films in the country to use digital audio. Benegal wanted to make sure his film was safe. He, therefore, locked his negatives at Prasad Labs in Chennai, one of the last remaining studios that still works with film. But tragedy struck. A water spill, the lab said, spoiled the original negatives. Benegal was heartbroken. “In my mind, the original negative was in the best lab in the country, safe and stored correctly. I should have checked continuously, spoken to them about storage conditions. But those were things one never knew back then and one learns in hindsight,” he says. Benegal has spent the last decade or so finding ways to salvage the film. “There’s a tiny sliver of hope. The Taiwanese filmmaker Edward Yang who was on the jury of one of the festivals where English, August won an award loved the film and asked the Taiwan Film Archives to buy a 35mm print. There is a low contrast print with the French television network La Sept-Arte that co-produced the film. I am planning to scan these digitally frame-by-frame at 8K and re-create a new archival digital negative and then make 35mm prints,” he says. But restoring the film in the digital age is even more expensive than what it cost Benegal to make the entire feature. “There are no organisations or funds I can access for support. I really have to fund it myself. I am hoping to do that in small steps,” he says. The ethereality of Agastya and his insipidity that acts as a function of class is truer perhaps of the urban millennials of today than it was ever before. Even though Chatterjee published the book in 1988 and Benegal adapted it to film in 1994, the relevance of Agastya’s non-story has hardly waned with time. Unpopulated by the need to wink at the headlines of the day, Chatterjee’s narration quietly restores the vastness of India, universalising cultural axioms and playing every bit the puppeteer of timelessness. It is that simple; nothing happens when nothing is supposed to happen. Aren’t most of us living that life of disproportionate indifferences, or as Agastya would say, ‘the absence of ambition, or the simplicity of it’?

The personality of Agastya Sen, the protagonist of English, August, finds a reflection in the way that many of India’s millennials are today | #FirstCulture

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)