The Beginning In

November 2002

, when the first atypical pneumonia case was reported in Guangdong, China, WeChat, China’s enormously popular social messaging app, was a dream. Those three months before the WHO office in Beijing received information about a ‘strange contagious disease’ that had left 100 people dead. The three months gave the deadly SARS-Co-V virus enough time to get a foothold and set off an epidemic that, within months, infected at least 8,000 people, killing 774 before dying out in the summer of 2003. Seventeen years later, on 30 December 2019, Li Wenliang, a young ophthalmologist, shared that “seven cases of SARS confirmed” to his WeChat group, called ‘Wuhan University Clinical 04’. Within days, the Public Security Bureau in Wuhan

called him

in and got him to sign a statement saying he was lying and disturbing public order. What made Li a hero was he published the statement on Weibo. In January, Li took to Weibo again,

saying

, ‘I started having cough symptoms on 10 January, fever on 11 January and hospitalisation on 12 January’. On 23 January, Wuhan, the epicentre of the epidemic shut down. There were far less than 700 publicly reported, confirmed cases of COVID-19 in China at that point of time. The truth is, China or the world did not know truly how many cases there really were. The world had never seen a quarantine of that scale — Wuhan alone had a population of 11 million. There were sporadic images coming through on the internet: people dying in the corridors of hospital, hospitals being overwhelmed. Doctors dying. In February, Li

gave

his final social media update, ‘Today the nucleic acid test result is positive, the dust has settled and the diagnosis has finally been confirmed.’ Within a week, he was dead, falling prey to the COVID-19 disease, that he had tried to warn the world about. It was clear that Chinese leadership, including Xi Jinping, knew about the outbreak well before the lockdown. In the

transcript

of a 3 February speech, Xi clearly states he had asked for the control of the pneumonia outbreak as early as 7 January. China swung into action as only China can – shutting down cities, factories, clearing land and

building

a 1,000-bed hospital from scratch in less than two weeks. These are measures that democracies could not, at that point, contemplate. On 19 March, Wuhan, the initial epicentre of the COVID-19 Pandemic,

declared no new case

, about 3.5 months after they reported the first case. Clearly, the virus could be beat — at a price. Ironically, China has

now instituted quarantines

against visitors from overseas. The pandemic had almost come full circle. Coronaviruses get their name from their spiked profile, which looks like a crown when viewed under a microscope. The SARS-CoV-2 virus, popularly called ‘The Corona Virus’, causes the COVID-19, a respiratory infection that can be lethal for older people with pre-existing health conditions like hypertension. Humanity has periodically dealt with coronavirus infections, that tend to be, for the most part,

upper respiratory tract infections

. Bats are considered the natural reservoir of coronaviruses, such as this one, and the one that caused the SARS outbreak about 17 years ago. The SARS-CoV-2 virus

is 96 percent identical

at a whole genome level to a bat coronavirus. It is also 79.6 percent similar to the coronavirus that caused SARS, which gives us a place to start for mechanism and cure. More on that later. While virulent WhatsApp images of bats in a soup have fed the imagination, scientists believe there was an intermediate host,

most likely the pangolin

. That’s because the coronaviruses isolated from smuggled pangolins were between 85-92 percent genetically identical to the coronavirus currently causing havoc in humans. Pangolins are internationally banned, but are still smuggled into China, where they are prized for their scales in traditional Chinese Medicine and for their meat. Which is why they feature in the live animal markets like the one in Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan. These markets are called ‘wet’ because of the spillage from aquatic tanks and the blood from the slaughtered animals. In the spattering from the slaughter,

viruses can jump from animal to man

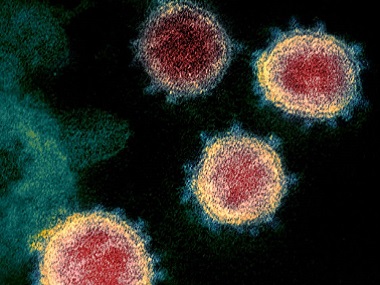

. [caption id=“attachment_8173221” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

The SARS-CoV-2 virus, popularly called ‘The Corona Virus’, causes the COVID-19, a respiratory infection that can be lethal for older people with pre-existing health conditions like hypertension. Representational image. AP[/caption] The SARS epidemic is suspected to have

started in a wet market

, with civets as the assumed intermediate host. Camels were considered to be the

intermediate host in the MERS epidemic

. The Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, which had a section with wildlife, has been the prime suspect for this pandemic. At least, that’s the theory. A

Lancet paper

considering the history of 41 early patients showed a significant number did not visit the wet market, and importantly, the earliest case did not. Given this Bin Cao, one of the co-authors

wrote

, “Now it seems clear that [the] seafood market is not the only origin of the virus,” he wrote. “But to be honest, we still do not know where the virus came from.” To be safe, China

shut down the market on 1 January 2020

. Why do origins matter? The Centre for Disease Control (CDC) in America

says

that three of four new infectious diseases come from animals. Knowing how and controlling for this is important to prevent future pandemics – this is something our bodies have not faced and have no immunity for. At the very least, given the global economic and human carnage, there need to be very strict slaughtering rules. China

shut down

wildlife trade, which many conservationists hailed as a positive step. However, there are loopholes. The ban does not cover animal use for

medicinal uses or fur

, leaving open the door for future animal-human jumps. How does the virus work? The virus particle consists of a fatty sheath in which spike proteins are embedded, and which surrounds a strand of RNA. There are other proteins provided structural integrity, but let us focus on the sheath, the spike and the RNA, because these hold the key, quite literally. Let us start with the sheath: Washing one’s hands with soap breaks open the sheath. Washing thoroughly and long ensures every virus particle (hidden in crevices or under nails) is attacked. The spike is what enables the virus to enter our cells. The virus needs to enter our cells to reproduce — it cannot do so on its own. If the spike protein is the key, what is the lock? The lock, researchers have found, is the ACE2, a protein found on the surface of many cells in the human body, especially and significantly for this pandemic,

the lungs

.

ACE2 functions in a complex of proteins

that modulate vascular functioning. Importantly, ACE2 appears to have a

significant role to play in organ protection

and blood pressure control, which is why persons with blood pressure, or hypertension, seem to have a

rougher time during COVID-19 infections

. A key ingredient of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is the the replication-transcription complex, which is what makes more RNA copies of the virus. This is important. Human cells make RNA from DNA — they have no machinery to make RNA from RNA. This act is foreign, and as such makes a great target for anti-viral drugs. Remdesivir is an antiviral drug developed by Gilead Biosciences, to work against Ebola, another RNA virus. In trials, this was shown to

mess up

viral RNA replication. The hope is this should work here too, which

very limited trials

show promise. However, the question also is will Remdesivir be available quickly and cheaply enough? And in the quantities required? Other early (very small) trials

showing promise

include treating COVID-19 patients with a combination of anti-HIV drugs. However, there have been

other trials

that show that this combination of lopinavir and ritonavir,

don’t really do the trick

, lessening death rate by only 5.8 percent over the control group. Others say that this trial is not reflective of the efficacy, because patients had already been symptomatic for two weeks before starting treatment, and that 13 patients on the combo were stopped given the combo in the middle of the trial because of adverse events. In this kind of a battle, every arrow in the arsenal is important, and doctors in Kasturba Hospital

have been treating

COVID-19 patients with the lopinavir-ritonavir combo. Another approach is to trick the virus. This is the thinking behind APN01, a floating ACE2 if you will, made by Apieron Biologics. The hope is that APN01 will act as a honey trap for the virus, preventing from latching onto human cells. Data

from a trial

in China to check the effectiveness of APN01, the synthetic ACE2, is awaited. In addition, the virus, like RNA viruses are wont to do, is mutating. One paper, summarized that there are two known strains of SARS-CoV-2, the deadlier, “L” strain, and the older, “S” Stain. China’s initial cases were primarily from the L strain, which gave way

to the more docile S strain

. Others point out that one mutation does not a strain make. The important point is that these mutations pose challenges to vaccine development and building immunity, depending on where they occur within the virus. Comparisons with other large scale infections show that SARS-CoV-2 is more infectious than the seasonal flu and the 1918 Spanish Flu and about as infectious as tuberculosis.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus, popularly called ‘The Corona Virus’, causes the COVID-19, a respiratory infection that can be lethal for older people with pre-existing health conditions like hypertension. Representational image. AP[/caption] The SARS epidemic is suspected to have

started in a wet market

, with civets as the assumed intermediate host. Camels were considered to be the

intermediate host in the MERS epidemic

. The Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, which had a section with wildlife, has been the prime suspect for this pandemic. At least, that’s the theory. A

Lancet paper

considering the history of 41 early patients showed a significant number did not visit the wet market, and importantly, the earliest case did not. Given this Bin Cao, one of the co-authors

wrote

, “Now it seems clear that [the] seafood market is not the only origin of the virus,” he wrote. “But to be honest, we still do not know where the virus came from.” To be safe, China

shut down the market on 1 January 2020

. Why do origins matter? The Centre for Disease Control (CDC) in America

says

that three of four new infectious diseases come from animals. Knowing how and controlling for this is important to prevent future pandemics – this is something our bodies have not faced and have no immunity for. At the very least, given the global economic and human carnage, there need to be very strict slaughtering rules. China

shut down

wildlife trade, which many conservationists hailed as a positive step. However, there are loopholes. The ban does not cover animal use for

medicinal uses or fur

, leaving open the door for future animal-human jumps. How does the virus work? The virus particle consists of a fatty sheath in which spike proteins are embedded, and which surrounds a strand of RNA. There are other proteins provided structural integrity, but let us focus on the sheath, the spike and the RNA, because these hold the key, quite literally. Let us start with the sheath: Washing one’s hands with soap breaks open the sheath. Washing thoroughly and long ensures every virus particle (hidden in crevices or under nails) is attacked. The spike is what enables the virus to enter our cells. The virus needs to enter our cells to reproduce — it cannot do so on its own. If the spike protein is the key, what is the lock? The lock, researchers have found, is the ACE2, a protein found on the surface of many cells in the human body, especially and significantly for this pandemic,

the lungs

.

ACE2 functions in a complex of proteins

that modulate vascular functioning. Importantly, ACE2 appears to have a

significant role to play in organ protection

and blood pressure control, which is why persons with blood pressure, or hypertension, seem to have a

rougher time during COVID-19 infections

. A key ingredient of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is the the replication-transcription complex, which is what makes more RNA copies of the virus. This is important. Human cells make RNA from DNA — they have no machinery to make RNA from RNA. This act is foreign, and as such makes a great target for anti-viral drugs. Remdesivir is an antiviral drug developed by Gilead Biosciences, to work against Ebola, another RNA virus. In trials, this was shown to

mess up

viral RNA replication. The hope is this should work here too, which

very limited trials

show promise. However, the question also is will Remdesivir be available quickly and cheaply enough? And in the quantities required? Other early (very small) trials

showing promise

include treating COVID-19 patients with a combination of anti-HIV drugs. However, there have been

other trials

that show that this combination of lopinavir and ritonavir,

don’t really do the trick

, lessening death rate by only 5.8 percent over the control group. Others say that this trial is not reflective of the efficacy, because patients had already been symptomatic for two weeks before starting treatment, and that 13 patients on the combo were stopped given the combo in the middle of the trial because of adverse events. In this kind of a battle, every arrow in the arsenal is important, and doctors in Kasturba Hospital

have been treating

COVID-19 patients with the lopinavir-ritonavir combo. Another approach is to trick the virus. This is the thinking behind APN01, a floating ACE2 if you will, made by Apieron Biologics. The hope is that APN01 will act as a honey trap for the virus, preventing from latching onto human cells. Data

from a trial

in China to check the effectiveness of APN01, the synthetic ACE2, is awaited. In addition, the virus, like RNA viruses are wont to do, is mutating. One paper, summarized that there are two known strains of SARS-CoV-2, the deadlier, “L” strain, and the older, “S” Stain. China’s initial cases were primarily from the L strain, which gave way

to the more docile S strain

. Others point out that one mutation does not a strain make. The important point is that these mutations pose challenges to vaccine development and building immunity, depending on where they occur within the virus. Comparisons with other large scale infections show that SARS-CoV-2 is more infectious than the seasonal flu and the 1918 Spanish Flu and about as infectious as tuberculosis.

- Our healthcare sector, including testing capabilities, treatment infrastructure and monitoring facilities are dwarfed by our large population.

- Large sections of our people live in close proximity, where spacing of 1 metre between families, is a pipe dream.

Given this, what can India do? Part 2: How effectively will policies of travel restrictions and social distancing control the spread? The writer is the founder of the Sundaram Climate Institute, cleantech angel investor and author of The Climate Solution — India’s Climate Crisis and What We Can Do About It published by Hachette. Follow her work on her website ; on Twitter ; or write to her at cc@climaction.net .

)