After writing two books on the Ramayana, The Missing Queen and Sita’s Ramayana, I’m breaking up with the epic that has obsessed us for millennia. The reason: A new epic has entered my life — the Silappatikaram. Epics such as the Mahabharata and the Ramayana focus on war and the story of men, the fate of princes and kings. But the Silappatikaram is different — it’s a Tamil epic that focuses on a woman, Kannagi, who is possessed by rage after her husband is unjustly executed by the king of Madurai. Her rage transforms her into a goddess. The King, astounded at his own act, drops dead, Kannagi rips off her breast and throws it into Madurai, and the power of her fiery breast incinerates the city. The best part? It’s written by a man, who is known as ‘Ilango Adigal’ (the prince who is also a monk). Legend has it that after a prophecy named him the next king, he renounced his claim to the throne in favour of his elder brother, and became a monk. He was a Jain monk who wrote an erotic epic. A prince who dedicated an epic featuring the king-destroying rage of a common woman, to his brother, a king. A man who wrote an epic poem of a woman’s quest for justice. In this one epic, so many paradoxes for us to wrestle with. (And that’s why he’s the subject of my latest book, The Prince.) But the prince-ascetic and his epic offered me something new that the Ramayana couldn’t. Ilango Adigal and Silappatikaram helped me realise that rage is necessary for justice and transformative change.

It seems to me that we have forgotten the myths and the epics that may serve us best in this time, the time of #MeToo, the era that has followed the brutal Delhi gang-rape of 2012.

The stories of the past that we choose to retell, from the Ramayana for example, inform our beliefs and our idea of role models — patterns of behaviour that we are unconsciously programmed to repeat. These patterns, subtly, insidiously, define many aspects of our lives — not just our marriages, but also our roles within relationships. Our concept of what it is to be a good son or daughter. Our ideas of right and wrong, of what’s acceptable and unacceptable. We aspire to be a leader like Ram, or a good brother like Lakshman, a wife like Sita. [caption id=“attachment_6239291” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Representational image. Wikimedia Commons[/caption] This is, for many including me, regressive and claustrophobic. The ‘values’ of tradition were typified in the silent, submissive chastity of Sita. Or in the sacrifice of Sati, who immolates herself to avenge her father’s slight to her husband’s honour. Or in the deeply disturbing death of Shambuka, the Shudra ascetic who is killed by Ram. But for someone who does not wish to suffer Sita’s fate; nor face the mutilation that is visited upon Surpanakha when she expresses her desire; or who dreams of a different fate for Shambuka and for Ekalavya, the untouchable boy who dreams of being a warrior but who must maim himself to honour his Brahmin teacher, what do the stories that have been handed down in the shape of our myths and histories, offer us? The Silappadikaram offered me something new; it is an epic that realised how necessary empathy is to reconcile the ruler and the ruled, man and woman, spirituality and sexuality, and how fundamental empathy is for justice. This empathy is only possible when we step out of the roles assigned to us. Empathy is nurtured through stories and literature, which allow us to imagine ourselves in different roles, places, contexts and bodies, and understand different emotional realities. There are other stories as well that can help us, perhaps, in time, to invent a new, secular mythology that can shape more egalitarian, empathetic beliefs. The philosophic movement that preceded the invention of the zero, shunya, is Shunyata. And one of its greatest proponents is Nagarjuna, a great scholar and philosopher who at one time is reputed to have been the head of the famous ancient university of Nalanda. Legend has it that Nagarjuna dived into a lake and retrieved a treasure trove of lost texts, known as the Prajnparamita texts. These were one of the treasures, known as terma by the Buddhists, that had been strewn across the earth and hidden away by the great tantric master Padmasambhava (a boddhisattva, who sought Buddha-hood to benefit all sentient beings) and his disciples. In times when the tradition is lost or forgotten or misinterpreted, these hidden texts are suddenly rediscovered and can provide illumination, guidance and enlightenment. My favourite one of these texts is the very short Heart Sutra. It talks about shunyata, about form and emptiness and the relationship between the two, and offers insights that can lead to freedom, nirvana, enlightenment. The Heart Sutra ends with a line that the Dalai Lama translates as: “Go, go beyond, and thoroughly establish yourself in Nothingness!” Not only are we nothing, but the Heart Sutra also tells us we should aspire to the state of nothingness and be nothing. Also read on Firstpost — The Prince: An excerpt from Samhita Arni's fourth book, a historical fiction inspired by a Tamil epic This runs completely in contradiction to every single rule or expectation that I was brought up with. I was told to be first in class, I was told that it was very important to aspire to something, to have a goal, to be ambitious, to be someone. And not just me. I meet many children who already feel burdened by the expectations imposed on them. Already at the ages of 10 and 11, they are thinking about careers, family, professional choices, colleges, Ivy Leagues, IIT coaching, SAT scores. Yet we take pride in this achievement-oriented style of thinking. So how can being nothing be a good thing? It might be the right thing for a Buddhist monk or nun, but how can a dose of nothingness be beneficial to society today? Why should we teach this to our children, or to students in colleges? But with this idea of nothing, you can, in fact, be anything.

You can choose your values, instead of merely adhering to those of your family or culture. Nothingness can be deeply empowering and liberating.

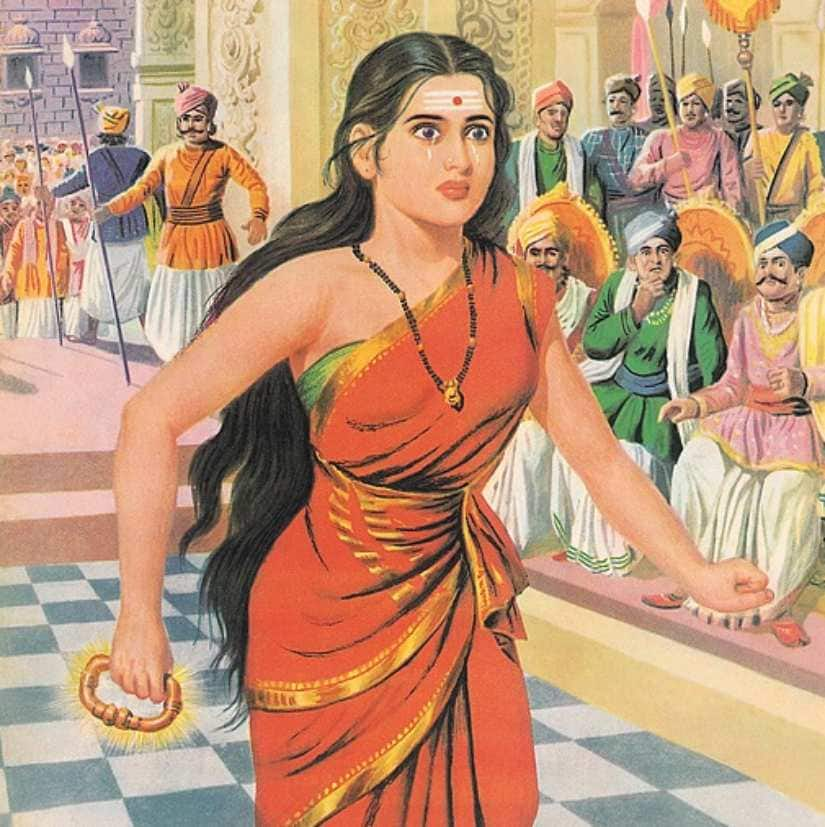

It is the reason why for many, Buddhism is not merely a religion but also a movement for social reform. It is a revolution — it cuts away at the linear ideas that we have, it works towards zero hierarchies and power paradigms, it dismisses ideas of gender and biology that impose limits on us. There are other stories, in other traditions, that talk of the possibility of not being fettered by forms and identities, but seeing past these. We live in the times of ‘love jihad’, of increased fear and paranoia about crossing or blurring lines between religions and castes. One of the original love jihadis was the 16th-century poet and mystic Shah Hussain, from Lahore. Shah Hussain fell in love with a 16-year-old Brahmin boy (not a girl, let me repeat — a boy) named Madho Lal. This love underwent many trials, and long separation. Eventually love prevailed and the lovers were united, merging into one form — Madho Lal Hussain. The shrine of Madho Lal Hussain, where Shah Hussain and his lover are buried, still exists in Lahore. [caption id=“attachment_6239311” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Kannagi from Silappatikaram. Facebook[/caption] What do the Silappatikaram, Shunyata and the story of Madho Lal Hussain teach us when taken together that the Ramayana doesn’t? For me it is this: that one cannot truly imagine the plight of another, or envision a future for oneself, without empathy. And for empathy, we must learn, at the very least, a fragment of nothingness, for it is only then that we can step beyond the boundaries drawn for us by the identities imposed on us, and begin to understand the emotional experience of another. This is key to healing the schisms and the splits that we have created by holding so tightly onto places in hierarchies, so tightly onto identities that bind and constrict our understanding and our capacity for compassion, in order to envision a future that transcends binaries. For myself, it is time to move past the Ramayana and the other stories from the past that we are familiar with, and the hold these have for us in terms of ideas of leadership, the roles of men and women, and even the way these narratives limit the expression of sexuality. There are other myths, from a multiplicity of traditions, that offer us different ways of being — many more than I have written about here. The story of the serpent king’s daughter from The Lotus Sutra, the Manimekalai and the story of Sulasa, for example, offer us empowering stories of women and girls from the past. The poetry of Andal and Nammalvar, and many other poets from the Bhakti tradition, can offer us a way to perceive the spiritual in desire, allowing us greater freedom to express love and desire. There’s so much that the boundary-crossing stories of Lal Ded and Sarmad the mystic can offer us. It’s time for a new, secular mythology. For our children and our adolescents and even ourselves, so that we can shape a more equal, compassionate, empathetic, and liberated tomorrow. Samhita Arni is the author of Sita’s Ramayana_,_ The Mahabharata - A Child’s View_,_ The Missing Queen and The Prince

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)