As more voices join the campaign to end FGM (female genital cutting) or ‘khatna’ among the Dawoodi Bohra community in India, will the misogynistic practice finally end?

“The visual image of the rusted razor that sliced through my clitoris and the memory of the excruciating pain that ensued continues to traumatise me. How can the act of surreptitiously luring a six-year-old child into removing her innerwear and then cutting off the most intimate part of her body be justified?” asks a Bohra woman from India as she recounts how Female Genital Cutting (FGC) or ‘khatna’ was performed on her, without an anesthetic or her consent. Many such voices of dissent come to fore as Bohra women, men and the many activists refuse to settle for the inconsistencies in the cultural and religious narratives passed down to them over generations. They are asking profound questions, persistently seeking dialogues, challenging patriarchal power structures, taking control of their bodies and most importantly creating counter narratives about ‘khatna’, thus empowering the community. What is FGM? FGC or Female Genital Mutilation refers to all non-therapeutic procedures that involve the total or partial removal of the external female genitalia. According to UNICEF at least 200 million females today have undergone FGM. After UN General Assembly voted to work for the elimination of FGM by 2030, 23 countries in Africa have banned the practice. Just a few months ago, in a landmark case in the history of Bohras, a Bohra priest in Australia was sentenced to 11months of Jail time for conducting FGM on 2girls thus perpetuating the practice in the community. No law against it exists in India. WHO classifies Female Genital Mutilation into four major types: 1.Clitoridectomy (partial or total removal of the clitoris), 2.Excision (partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora), 3.Infibulation (narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal), and 4.other forms (pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterising the genital area). [caption id=“attachment_3009230” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

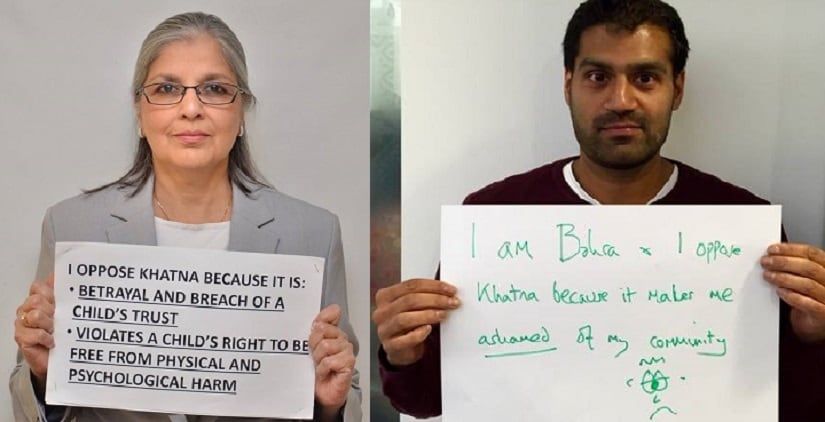

From Sahiyo’s campaign against ‘khatna’ or FGM[/caption] FGC in India In India ‘khatna’ is practiced in the Dawoodi Bohra, a sub-sect of the Shia Muslim community from Gujarat that originally migrated from Yemen. Most Bohras practice the FGM Type1 in which the prepuce (tip of the clitoris) is removed though at times the cut gets deeper when the child resists. The procedure is performed by mullanis (women who have a semi-religious standing), by daimas (midwives) and sometimes by doctors when the girl is between 6-9 years old. Bohras believe that ‘khatna’ is not same as Female Genital Mutilation as they cut the tip of the clitoris (Type1) and therefore similar to male circumcision. Contrary to that belief, research tells us that even Type1 of FGM is anatomically equivalent to penectomy (surgical removal of the penis). The religious clergy claims that FGC is a ritualistic practice that comes from 10th century book of jurisprudence called ‘Daim-al-islam’ (though there is no mention of it in the Quran). The justification that it is done for hygiene reasons is also untrue as no medical study validates the claim. Most members of the community will agree that ‘khatna’ is done to restrain a woman’s sexual urge so that she won’t indulge in so called sexually deviant behaviors; such as masturbation, flirtation, pre-marital or extra marital affairs. In certain countries where FGM is mandated, an uncircumcised woman may even be seen impure, unhygienic, promiscuous, incomplete and thus unacceptable in the community. Tasleem, an activist working to end FGM, narrates an incident to substantiate the patriarchal views of certain community members. A female doctor asked a parent who was reluctant to get FGM done “Do you want your daughter to have multiple lovers?”. Mumbai-based journalist, Aarefa Johari, who has been speaking out against FGC asserts, “How can any religious, ethical or moral defense be made for preserving a cultural practice that potentially damages a woman’s health, alters her anatomy and interferes with her sexuality?” and rightly so.

![fgm 2]()

FGC can be a traumatic experience for a child (6-7 years old) who is developing her world view; leading to physical complications, psychological trauma, sexual ill-health. It is likely that many women anxiety, fear of infertility, low self-esteem and the physical manifestations of these include sleeplessness, hyper vigilance generations, loss of appetite, panic attacks, intractable dysmenorrhea et al. However, there are women who still believe FGC must continue for religious reasons. It seems that they find reasons to approbate the practice, a subconscious effort needed for psychological adjustment. Tasleem explains how the practice is perpetuated, “In many cases, the grandmother forces it down the throat. When parents of the girl child live in a joint family, with a family trade, it is impossible to disobey the elders. Friends congratulate the victim’s grandmother for the successful completion of ‘khatna’ without understanding the misogynistic nature of the practice. Many girls that go through type 4 FGM — which is just a ritualistic poke aren’t aware of the thousands who went through barbaric pain, suffered years of menstrual pain and sexual discomfort. And they feel that even after ‘circumcision’ if they have such a strong libido, they’d have become nymphomaniacs without it.” Socio-cultural influences have the potential to change the perception of pleasure as ‘khatna’ refutes the fundamental right of every woman to have healthy sex life which is also essential for psychophysical well-being of the person. In contrast male circumcision doesn’t affect man’s sexual pleasure, or the sex organ. In the last few years some people have been arguing that FGC enhances sexual pleasure for women as it exposes the clitoris by cutting off the hood, thus equating ‘khatna’ to clitoral un-hooding, a surgical procedure that is becoming famous in the West. However, it is unfair to compare the two considering the surgery is chosen by adult women to enhance sexual pleasure only if they happen to have excessive prepuce tissue that interferes with orgasm.

![fgm 3]()

For many years, the angst and trauma the Bohra woman experienced was possibly in conflict with the desire to gain parental and societal acceptance and fear of being ostracised. However today, the female agency is much stronger and they refuse to keep silent. The many debates and the activism In the past FGC was hardly a matter of public discourse, in fact lot of men in the community wouldn’t know about it till they got married. Gynecologists, urologists, and sexologists don’t necessarily know enough about FGM/C and might find it hard to understand the complex interplay of customs and traditions, female agency and the role they play in a woman’s sexual experience. But things are changing now. Way back in 1991, Rehana Ghadially a retired professor wrote about FGM in India for the first time breaking the silence around the custom in a paper titled “All for Izzat”. A decade later Tasleem (quoted above) initiated an online petition addressing the then Syedna (religious leader) to ban FGC among the Bohra Muslim community arguing that it reinforced the stereotype that Islam doesn’t give equal rights to women. More recently, ‘Sahiyo’, an NGO advocating against FGM is engaging in education, dialogue and collaboration giving the movement the impetus it needs. Their photo campaign publicised on social media, “I’m a Bohra”, gave voice and a face to those who support the banning of FGM. Speak Out on FGM, another collective launched a signature petition on change.org (garnering 50,000 votes) asking for the government of India to ban FGM. However, the community was deeply disappointed when Syedna Mufaddal Saifuddin, the spiritual head of Bohras categorically said that ‘khatna’ should be continued even if there is opposition to it. “It must be done. If it is a man, it can be done openly and if it is a woman it must be discreet. But the act must be done.” The activists hope that this is only a small setback and the many voices of dissent will eventually drive change. Tasleem asserts, “The clergy plays a very important part in how a religion evolves. Such reactionary thinking does no one any good. By changing his stance he will get a chance to save millions of girls from a wicked, patriarchal practice, and to be seen as a truly evolved spiritual guide.” As the activists advocate to legally ban the practice, they understand that a radical culture change from the ground up is imperative, one that promotes zero tolerance to any and all forms of excision. Like most other forms of gender-based violence, only if the social constructs of masculinity and power that justify acts of controlling a woman’s body and sexuality are broken will FGM end. To read more of the writer’s journalism, log on to

www.sindhusarathy.com

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)